Contents of Article

- Summary

- What is a needs analysis?

- What is required in a needs analysis?

- Section 1: A Sport-oriented needs analysis

- Section 2: Profiling the athlete (athlete-oriented analysis)

- Section 3: Comparative analysis

- Are there any issues with needs analysis?

- Is future research needed with needs analysis?

- Conclusion

- References

- About the author

Summary

The needs analysis is the process of determining what qualities are necessary for the athlete, the sport, or a combination of both. Doing an in-depth needs analysis allows the strength and conditioning coach or sports scientist to identify what physical qualities are most important for their athlete to perform well in their sport. It also provides an injury analysis of the sport and therefore helps the coach to tailor training towards preventing such injuries.

On top of all this, the physical profile of the athlete also helps the coach understand the strength and weaknesses of their athlete and therefore highlights where the majority of the training time should be spent.

What is a needs analysis?

Conducting a detailed analysis of the physical demands of a sport and physical profile of the athlete is known as a ‘needs analysis’. Simply speaking, a need analysis can be conducted on both the sport and the athlete. Performing a needs analysis prior to designing a training programme is essential as it provides vital information on the demands of the sport, the current profile of the athlete, and what the athlete needs to be successful in their sport.

Understanding these will typically provide enough information for the strength and conditioning coach to create an appropriate and effective training programme.

The primary objectives of any athletic training programme are typically two-fold:

- Prevent Injury

- Enhance Performance

It is consistently proven that well-designed physical training programmes can reduce injury rates (1, 2) and improve athletic performance (3, 4, 5, 6, 7). As a result, it is the primary responsibility of the strength and conditioning coach to ensure both these training objectives are achieved. This responsibility means a strength and conditioning coach will conduct an extensive needs analysis on the sport, and spend large quantities of time planning their physical training programme.

What is required in a needs analysis?

As previously mentioned, a needs analysis can and should be conducted on both the sport and the athlete. A sport-orientated needs analysis will look at the specific demands of that sport. For example, the duration of the sport, is it land-based or water-based, and is it an individual or team-based sport? On the other hand, an athlete-orientated needs analysis will assess the athlete’s current physical profile – i.e. age, gender, weight, strength, speed, and power.

Identifying the demands of the sport are often done first as this allows the coach to identify what qualities the athlete needs to possess in order to perform well in that sport. Using the 100m sprint as an example, the coach would identify that speed is a vital component in performing well in that sport. For that reason, the coach may decide to test the athlete’s speed in order to identify their current ability and what segments of their speed needs work. Therefore a needs analysis is often conducted in three parts:

- Section 1: Sport-orientated needs analysis

- Section 2: Profiling the athlete (athlete-orientated analysis)

- Section 3: Comparative analysis

Section 1: A sport-oriented needs analysis

Sport analysis

Examples include:

- What sport is it; competition schedule; land- or water-based, what competition level (i.e. professional or amateur); the duration of the sport; are there any stoppages/rest times; what position does the athlete play; is there more kicking, running, throwing in that position; maximal and/or sub-maximal speed; what equipment is used.

Injuries analysis

Examples include:

- Common injuries in that sport and position; injury frequency; average time-loss from particular injuries; time of year injuries; surfaces; predisposing factors (e.g. previous injury).

Biomechanical (kinematic and kinetic) analysis

Examples include:

- Kinematics of the sport–specific movement, i.e. sprinting, jogging, walking, shuffling, lateral shuffling, sitting, twisting, jumping (one-leg/ two-leg), throwing, balancing, lunging, and tackling.

- Kinetic of the sport – all force-time; power-time; velocity-time characteristics (i.e. peak force, rate of force development, eccentric rate of force development, impulse, ground contact time, torque, peak power output, average power output, peak velocity, time to peak velocity, and average velocity).

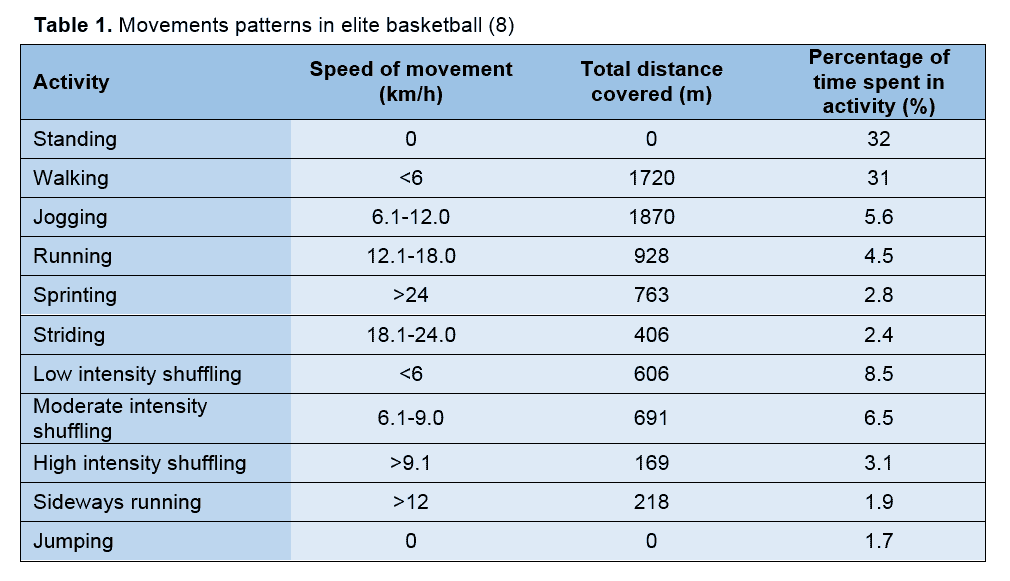

Table 1 provides an example of how this data may be displayed.

Aerobic analysis

Examples include:

- Average heart rate, maximum heart rate, VO2 max, average VO2, and total distance.

Anaerobic analysis

Examples include:

- Lactate threshold, anaerobic capacity, anaerobic power, total number of sprints, sprints per minute, high-intensity running, total jumps, total number of direction changes.

All this information aims to do is simply dissect the sport into manageable segments so that the strength and conditioning coach or sports scientist can prescribe a more accurate, and potentially a more beneficial training programme.

Section 2: Profiling the athlete (athlete-orientated analysis)

Athlete profile

This will include performance testing to identify their strengths and weaknesses.

Examples include:

- Their position, competitive level (e.g. professional), date of birth, gender, height, weight, height-weight ratio, BMI, body fat, chronological age, biological age (i.e. maturity offset or age of peak height velocity), technical training age, athlete’s injury history, athlete’s strengths and weaknesses (e.g. power, acceleration, balance, mobility, flexibility).

Athlete’s objectives

Examples include:

- Personal goals, coach’s goals for the athlete, and player-coach agreed goals.

Section 3: Comparative analysis

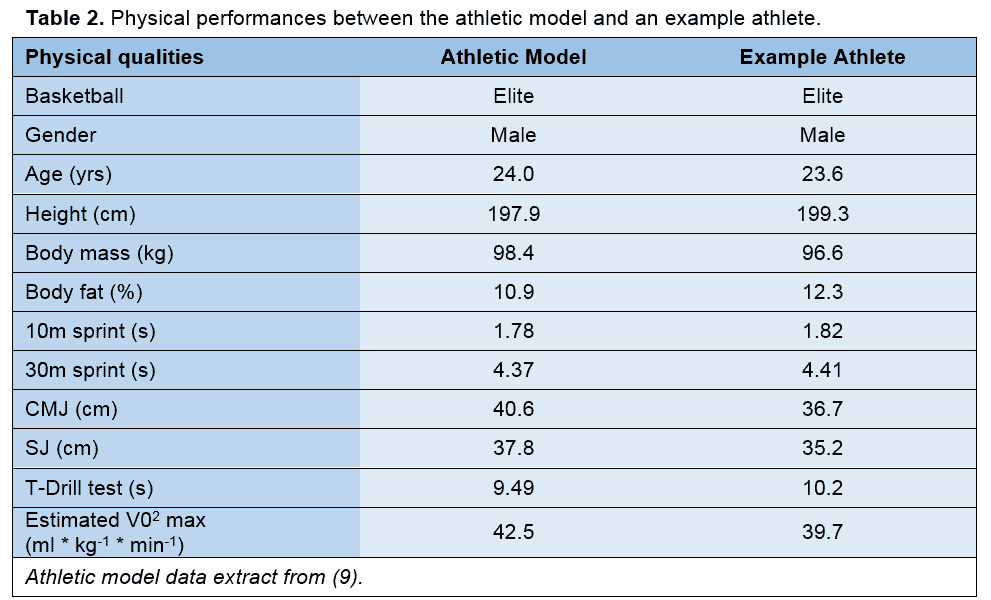

When the information has been gathered on both the sport and the athlete, it is then time to compare the two and identify how the athlete compares to the common profile of the athletes in that sport. Table 2 provides a simplistic example of how this comparative analysis may be performed. In the table, you can see how the ‘example athlete’ compares to those of a similar population (e.g. elite male basketball players).

Although this exhaustive list of information is daunting, these are just examples of the data a strength and conditioning coach or sports scientist may compile before designing a training programme for their athlete. A common rule of thumb is ‘the more detail, the better’, as this allows the coach to be very specific with their programming. Once the demands of the sport have been analysed in combination with the athlete’s personal training goals and those set by the coach, then the planning process of the training programme can begin.

Are there any issues with needs analysis?

Whilst the information gathered when creating an in-depth needs analysis can be extremely helpful for the programme planning process, gaining the desired information for that particular sport can often be problematic. This is often either due to a lack of research data on that particular sport, or difficulty gaining access to the required data as this is often in research-based journals.

On the other hand, as some sports (e.g. football and rugby) have been extensively researched, it is often difficult to make sense of all the data and design an optimal training programme – often an information overload. In such scenarios, it is suggested that the strength and conditioning coach or sports scientist simply decides what the primary objectives of the programme are, and avoids over-complicating things – stick to the simple, yet effective principles of training.

Therefore, the common issues surrounding designing a needs analysis are:

- Lack of research data on that particular sport.

- Inaccessibility to available information.

- Overwhelming quantities of information, which may lead to over-complication.

Is future research needed with needs analysis?

As previously mentioned, there is a lack of current physiological and biomechanical data available on a large quantity of sports, meaning there is a vast opportunity to investigate the physical demands of many sports from professional to recreational levels. Whilst some researchers are currently creating practical and useful needs analyses for a number of sports (10, 11, 12), there is still an extortionate amount of sports without evidence-based needs analyses. Consequently, the two following suggestions would be useful research topics for a vast majority of sport science graduates:

- Analyse the physiological and biomechanical demands of sports from a professional to recreational level.

- Develop sport-specific needs analyses for male, female, adult, youth, masters, professional, elite, amateur and recreational sports.

Conclusion

To design a well-planned, holistic, and effective physical training programme, it is essential the fitness coach researches and designs an in-depth sports-specific needs analysis for their athletes. Failing to do so could lead to a less-than-optimal training programme and even injury.

The information in this article provides the strength and conditioning coach and sports scientist with the required information needed to make calculated assumptions on what demands of the sport they should be considering when conducting a need analysis (e.g. common injuries and total distance covered). This is an essential process required to maximise the effect of the physical training programme and prevent, or at least reduce the likelihood of injury in their athlete(s).

- Malliou P, Rokka S, Beneka A, Mavridis G, and Godolias G. Reducing risk of injury due to warm up and cool down in dance aerobic instructors. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 20: 29–35, 2007. [Link]

- Barengo, N.C Meneses-Echávez, J.F., Ramírez-Vélez, R., Cohen, D.D., Tovar, G., & Bautista, J.E.C. (2014). The Impact of the FIFA 11+ Training Program on Injury Prevention in Football Players: A Systematic Review. 2015. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(11), pp.11986–12000. [PubMed]

- Chaouachi, A., Hammami, R., Kaabi, S., Chamari, K., Drinkwater, E.J. & Behm, D.G. (2014). The combination of plyometric and balance training improves sprint and shuttle run performances more often than plyometric-only training with children. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(2), 401–412. [PubMed]

- Chaouachi, A., Hammami, R., Kaabi, S., Chamari, K., Drinkwater, E.J. & Behm, D.G. (2014). Olympic weightlifting and plyometric training with children provides similar or greater performance improvements than traditional resistance training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(6), 1483–1496. [PubMed]

- Ozbar, N., Ates, S. & Agopyan, A. (2014). The effect of 8-week plyometric training on leg power, jump and sprint performance in female soccer players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(10), 2888– 2894. [PubMed]

- Lake, JP and Lauder, MA. Kettlebell swing training improves maximal and explosive strength. J Strength Cond Res 26(8): 2228–2233, 2012 [PubMed]

- Ronnestad, B.R., Hansen, J., Hollan, I., & Ellesfen, S. (2015). Strength training improves performance and pedalling characteristics in elite cyclists. Scandanvian Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 25, pp. 89-98. [PubMed]

- Tack, C. (2013). Evidence-Based Guidelines for Strength and Conditioning in Mixed Martial Arts. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 35(5), pp.79–92. [Link]

- Abdelkrim, ND, Chaouachi, A, Chamari, K, Chtara, M, and Castagna, C. Positional role and competitive-level differences in elite-level men’s basketball players. J Strength Cond Res 24(5): 1346–1355, 2010 [PubMed]

- Köklü, Y., Alemdaroğlu, U., Koçak, F.U., Erol, A.E., & Fındıkoğlu, E. (2011). Comparison of Chosen Physical Fitness Characteristics of Turkish Professional Basketball Players by Division and Playing Position. Journal of Human Kinetics, 30, 99 – 106. [PubMed]

- Read, P., Hughes, J., Perry, S., Chavda, S., Bishop, C., Edwards, M., & Turner, A. (2014) A needs analysis and field-based testing battery for basketball. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 36 (3). pp. 13-20. [Link]

- Turner, E., Munro, A.G., & Comfort, P. (2013). ‘Female soccer: Part 1 – a needs analysis’. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 35 (1), pp. 51-57. [Link]