Can the Talk Test improve performance?

While sports technology continues to develop at a rapid rate, there are simpler ways to monitor your exercise intensity. One of these old-school methods is the Talk Test.

Talk Test: An old-school method in a modern world

To say it’s been a tricky time for the world over the past two years would be an understatement. But it seems many of us are now starting to emerge from our Covid hibernation. Around the world, things are beginning to return to normal as shops, cinemas, sporting arenas and gyms reopen. These reopenings have brought with them a sense of normality that many had longed for throughout the darker periods.

For some, though, when it comes to exercise, the idea of returning to their gyms may not be front and centre in their minds. Once we got over the initial idea that gyms and fitness centres would be closed for an extended period (and the rush to buy up ever-scarce gym equipment subsided), some began to find it quite enjoyable. We were being given the chance to train in our living rooms, gardens or in our local parks and trails. So, for some, the reopening of gyms may not see a total return to the old normal. This isn’t to say that people no longer have the desire to use a gym – there are obvious advantages, including more varied or specific equipment and potentially greater comfort during the winter months. But it seems likely that many will continue to train, at least occasionally, in the settings they became used to during respective lockdowns.

The idea of a shorter journey to our exercise space, enjoying the great outdoors, or saving some money by having a cheaper gym membership sounds great, but can we be sure that we’re getting equal benefits from our new training programs? Specifically, in this blog, we’re going to consider whether we are working at the right intensity for what we’re trying to achieve when we train. To be clear, this isn’t to say ‘are we working hard enough?’, as anyone can train until they throw up, but are we working in a way that fits our goals, be they a recovery, light, medium or hard day?

Now, as I write this, I can see you looking over at your tech pile and thinking you’ve got it all covered. You’ve got your phone with your subscription running app on it, you’ve got your heart rate belt, you’ve got your watch that tells you all you need to know, and that’s just the start of it. And I’m not saying that all of those things aren’t useful. But what if you forget something, you’re out of town, you didn’t remember to charge something, or you’re new to the game and haven’t amassed the whole Batman utility belt just yet? What can we use to measure our intensity of effort then? One such option is the Talk Test. You may have heard of this before, but today we’ll cover the what, when, why and should yous of this test to see whether it can help us get the most from our workouts in the simplest way possible.

So, what is the Talk Test?

The principles of the Talk Test were first proposed at least as far back as 1939 when a professor at Oxford University recommended mountaineers ‘climb no faster than they can talk’. The idea being that if they were working hard to the point where they couldn’t hold a conversation, then it might be too taxing for them to complete their climb. In the many decades since, exercise physiologists have continued to play around with the idea, mostly with regard to exercising for health. The thinking being that if you could just about hold a conversation, you were likely working hard enough to see some improvements to your health. More recently it has been shown that, in fact, the ability to talk is strongly linked with exercise intensity.

So, with a general idea of what the test is and knowing it might be linked to how hard we’re working when we’re training, let’s have a look at how we might consider implementing it.

Working in the right zones

As I mentioned above, training isn’t all about thrashing yourself every time you do some exercise. So, let’s have a quick look at what we mean by training zones and what this might mean for our training. We know that aerobic fitness is really important for both our health and athletic performance. But when we’re planning our training with some longer term thinking applied, it is important to manipulate the intensity (how hard), frequency (how often) and duration (how long) if we want to progress and consider appropriate recovery.

It’s likely that it might be our aerobic exercise that we continue to perform away from the gym now we’ve discovered the benefits of doing it outside. Typically, when programming such sessions, you have likely heard of us being interested in the percentages of our maximum heart rate and oxygen consumption (VO2) that we might be working at. This relates to our exercise intensity, and it is these heart rate or oxygen consumption bands that we’re interested in manipulating. Recommended guidelines are quite broad for training using heart rate when aiming for health benefits. For instance, the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) traditionally recommended exercising between 55 – 90% of maximum heart rate or 40 – 85% of maximum oxygen uptake for most individuals. When aiming for fitness improvement, it’s good to mix up our intensities throughout the week to improve all aspects of fitness, from speed and power through to aerobic endurance.

This can be very individual and will relate to how experienced you are, but you will likely know how hard you want to work to achieve your objectives. A reasonable rule of thumb is to consider three exercise intensity bands:

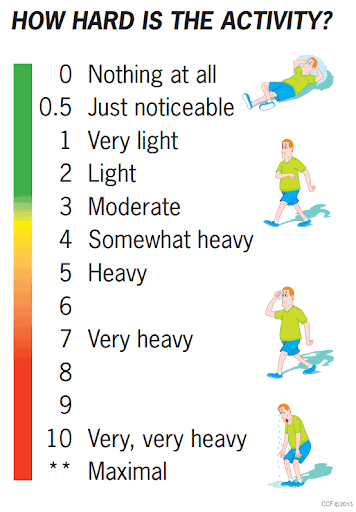

- Low-intensity work (would score a 3 to 5 on the ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) scale seen on the right). It would be reasonable to aim for this level once a week, often as a recovery.

- Moderate intensity work (5 to 7 on the RPE scale). This might be factored in once to twice a week.

- High-intensity work (7 to 9 on the RPE scale). This too might be incorporated once or twice a week.

Beyond the physical benefits, this manipulation also keeps our training from getting too boring, which can often lead to us quitting. Due to having a good understanding of the importance of tracking exercise intensity, many fitness enthusiasts find it useful but often difficult and sometimes tedious. Thankfully, there is good evidence that using the Talk Test can help us to plan our training by taking into account the intensity of that exercise in a simple, cost-free way.

How to perform the Talk Test

Summarising the above, we know that monitoring training is beneficial, though we may not always want or be able to use technology to help. Thankfully, we also know there is a correlation between our ability to talk during exercise and that exercise intensity. So how can we put it all together? Based on the intensity ratings and RPE scores above, we can consider that:

- Being able to speak comfortably relates to that low-intensity, sub 5 RPE score.

- For medium intensity, you can try counting as high as you can at a steady pace in one breath. Repeat this during your exercise at the same pace. If the number has reduced by more than a quarter, then you are now in the medium-intensity zone.

- It’s been suggested that at higher intensities or in very trained individuals, the talk test may be less effective in determining your training zone. Despite this, some have offered that when talking becomes too difficult, or only a word or two can be achieved, then this can be considered high-intensity.

Are you talking to me?

It seems the Talk Test offers a nice opportunity to very easily alter your exercise intensity between or during sessions. It works in most environments and all-but the most conditioned athletes at higher intensities. The downside is, it is admittedly hard to be as specific as you can be when using heart rate zones. Overall, the test is a useful, free method, especially for beginners and non-competitive exercisers. For those who are a little more serious, it would be useful for them to finetune their intensity zones by cross-referencing their ability to talk while they exercise against their heart rate when they are wearing their extra equipment. This knowledge can then be used when you’re equipment-free to increase the accuracy of the Talk Test.

One thing to keep in mind, though, is that depending on your goals, if you are looking to exercise to become a little more active or for health benefits, then any level of exercise is going to be hugely beneficial. If you’re able to consider factoring in low-, medium- and high-intensity efforts throughout the week, then all the better. Just be safe and take comfort in the knowledge that you don’t have to be giving James Bond a run for his money in the gadget stakes to make it worthwhile.

[optin-monster slug=”nhpxak0baeqvjdeila6a”]