Contents of Article

- Summary

- Why is strategy important in sports?

- Reverse engineering

- Build a malleable plan

- Summary

- About the Author

- References

Summary

When we speak of strategy, we often first think of the military, business or perhaps politics, and we may consider the term as ‘our plan to achieving victory or success’. These environments have been instrumental in our conceptual understanding of what strategy is and how to move our ideas to actions. As such, coaches can and should take the lessons learned, theories and concepts to guide our athletes towards reaching their performance goals.

A strategy is your athlete’s road map to achieving their performance goals. It is usually quite easy for athletes to identify what the desired goals are (destination), the issues often lie in how to achieve these goals (the route). As coaches, we are in a unique position to be able to facilitate building the route and even more importantly the daily habits, checkpoints, courses of action and contingency strategies for the journey.

This article will provide some recommendations and discuss some tools you can use with your athletes that can be used to ‘reverse engineer’ or work back from their outcome goals to fully understand the process and actionable tasks required to construct a winning strategy.

The next section of this article will discuss three principles that can add some structure to the process. They include some frameworks that coaches can use with their athletes to create their performance strategies.

- Know the landscape

- Reverse engineer

- Build a malleable plan

A high-level plan to achieve one or more goals under conditions of uncertainty’ (Freeman 2013).

Why is strategy important in sports?

This principle has two main considerations:

- Know Your Athlete

- The Environment.

Know Your Athlete

This relates to understanding where your athlete is right now concerning their goal. It is non-negotiable to conduct an open and honest assessment of all aspects that can be controlled. Ranging from individual physical qualities such as speed or tactical knowledge, to lifestyle, funding, or coach/teammate relationships. The notion of self-awareness in a competitive/battle-type situation is supported by the famous author of ‘The Art of War’ Sun Tzu (2007) who stated;

“If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle”.

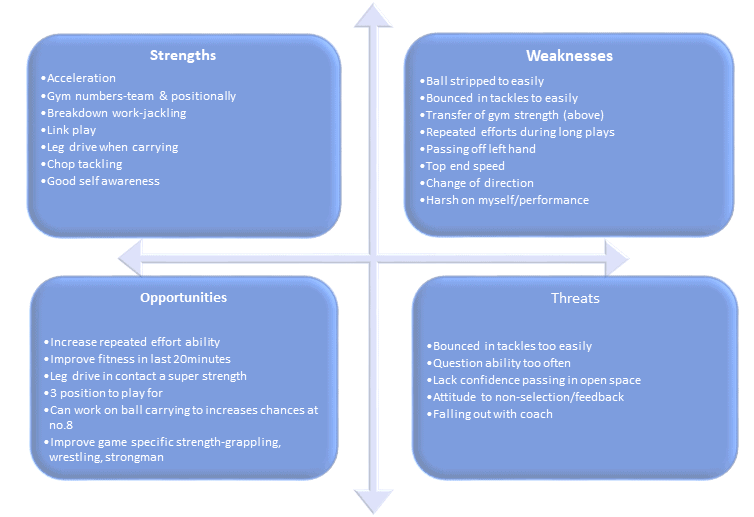

To help your athletes to improve their self-awareness and identify where they are on their journey to their goals, they can use a popular business analysis tool called a S.W.O.T analysis.

Create an extensive list of every possible controllable factor and place them into one of these four categories: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats (Fine 2009). Once you have a long list, take the top 3-5 essentials from each category. Now you have your major blocks to focus on.

Here is an example S.W.O.T analysis for an aspiring backrow rugby player who has given an honest, open assessment of themselves.

The Environment

The environment refers to all aspects generally outside of your athletes’ control which they need to have an awareness of to build an effective plan. Such as competition schedules, expected performance standards, club status/reputation, teammates, coaches’ personality/approach and the pathway to the top in your sport.

Whilst your athletes may not be able to directly influence these aspects, they do need to understand they can indirectly influence these through their decisions and actions. For example, how they conduct themselves in training and around the club/training environment or their reactions to adverse decisions/setbacks such as non-selection, loss or injury.

Alternatively having a realistic image of self is invaluable, such as the awareness of a player signed as third or fourth choice in a position may not be likely to get extensive game time and may be loaned out for game time. Understanding and knowing their landscape can help them to set realistic goals and manage the expectations of their rise to the top. This is useful in avoiding disappointment and crushing confidence as a result of unrealistic expectations.

[optin-monster-shortcode id=”zmduwq9qz4orwfm5dng4″]

Reverse Engineering

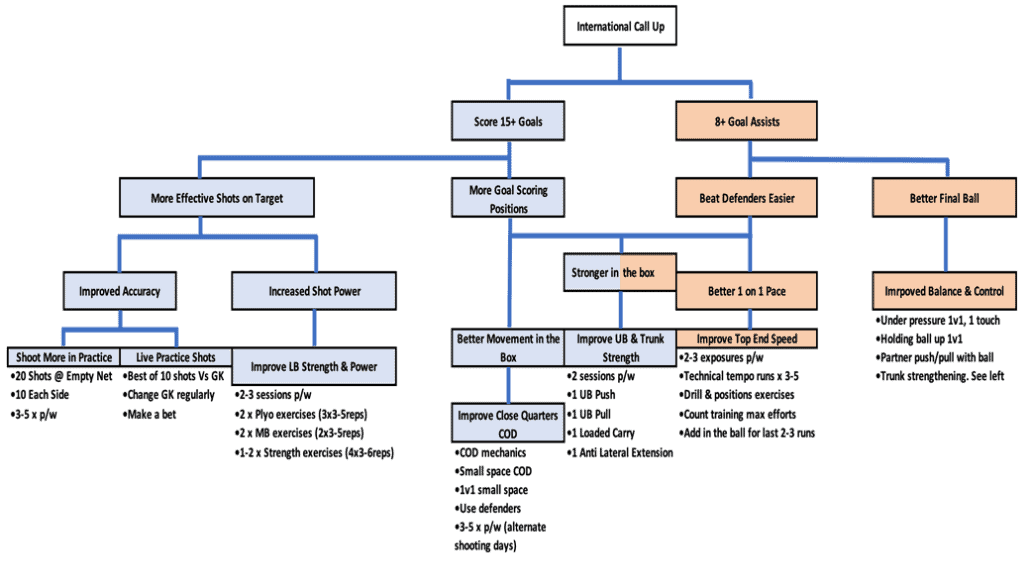

Reverse engineering refers to working backwards from the finished product or desired outcome to establish the exact pathway to success. Your athletes can work from a broad goal long-range goal back to the daily tasks which must be conducted to achieve the outcome.

This flow chart below is a section of the plan built for a Premiership football player who reverse-engineered their goal of becoming an England International. They were supported in building the plan from the top-down until they reached the daily actions that needed to be done. They used big sports-specific metrics such as minutes played, goals scored and assists as barometers. As well as smaller measures including jump height, goals scored in shooting practice vs. the goalkeeper in training and back squat 3RM.

Build a malleable plan

The first part of building a malleable plan is to have a plan in the first place. Once your athletes have reverse-engineered their plan, you can help them assign checkpoints or gateways to assess progress. These gateways can act as an excellent way to step back and take an objective 30,000ft view of how the plan is going. If it is working, then continue; if it needs altering then support your athletes in adjusting focus and pushing on.

The checkpoints can be defined by yes/no or pass and fail metrics, and the success/failure of the plan can be made quantifiable through a rating or scale.

Some examples may include:

- On a scale of 1-5, how successful would you say you have been in achieving your goals? (5 being very successful).

- Out of 10 practice sessions, how many sessions did you complete?

- How many shots did you score out of 100 attempts?

The most important part of building a malleable plan is having the ability to take stock and then adjust.

A gateway or checkpoint is an effective way to help your athletes hold themselves accountable for their progress if the plan has assessed the landscape and then reverse-engineered the outcome, then it will be able to easily identify the specifics of why the plan was a success or not. This is an invaluable process in the revaluating and resetting practice which needs to be done regularly to check the route to success.

Not all elite athletes will make it to the highest level of their sport. Some sports pay well if you make it to the top, but the vast majority do not. The reality is that your athletes can’t afford to have a detailed, structured plan and their time and effort need to be correctly distributed to areas of their personal development such as deliberate practice, physical competencies, movement skills, regeneration, mental performance skills, technical tactical knowledge.

Furthermore, sport can be a cruel world and your athletes can be one injury away from their dreams being swiped away. Help your athletes to do their due diligence for life after sport and set up some contingencies or exit strategies through continued education, work experience, savings and health insurance.

Summary

In summary, talent alone is not enough to make it to the highest level in sport and have longevity there. Building a road map and a route with your athletes will take out the guesswork, increase engagement with the process and keep things fluid in times of difficulty and change. Benjamin Franklin summarised strategy in this context succinctly when he said ‘failing to plan is planning to fail’.

- E. Irick. NCAA Sports Sponsorship and Participation Rates Report. URL: https://ncaaorg.s3.amazonaws.com/research/sportpart/Oct2018RES_2017-18SportsSponsorshipParticipationRatesReport.pdf

- Colvin. Talent is Overrated: What Really Separates World-Class Performers from Everybody Else. Portfolio. 2008.

- G. Fine. The SWOT Analysis. Createspace Independent Publishing Platform. 2009.

- Strategy: A History. Oxford University Press. 2015.

- Sun Tzu. The Art of Filiquarian. 2007