Contents of Article

- ACL rehabilitation: The pain and the background

- Why do ACL injuries occur so often?

- The power of positivity during ACL rehabilitation

- ACL rehab: Phase 1, pre-surgery

- ACL rehab: Phase 2, post-surgery

- ACL rehab: Phase 3, home time, and the first 4-6 weeks

- The secret of prepped meals

- ACL rehab, Phase 4: Progression and return to exercise

- Some final food for thought

ACL rehabilitation: The pain and the background

I can still remember the time I ruptured my own anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in graphic clarity – hearing a sound similar to a gun exploding, feeling a wave of pain coursing through my entire body, and knowing that I faced a lengthy recovery … all those feelings are still vivid two years later. And it’s no surprise – tearing your ACL is one of the worst injuries an athlete can suffer. If you work in sport or with athletes, you will either have witnessed an ACL blowing or know someone who has experienced it – the pain on the person’s face can be unbearable to watch!

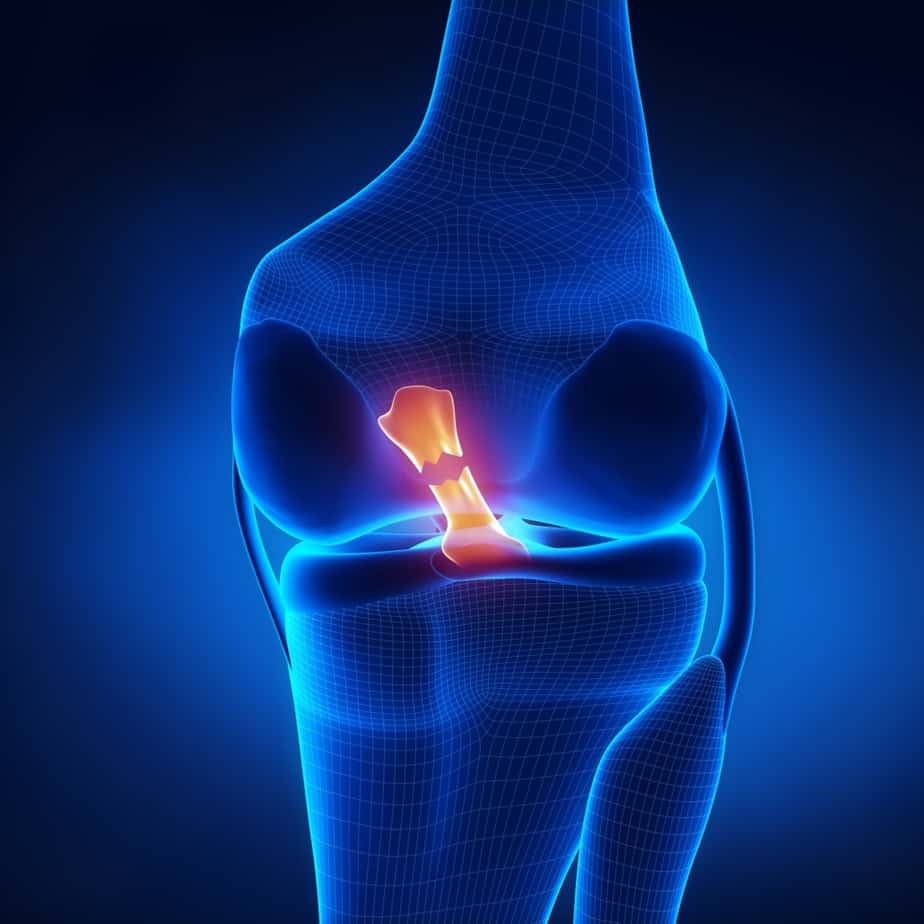

The ACL is one of the key ligaments in your knee and is pretty important to help stabilise your knee joint. Put simply, rupturing your ACL is something you would really prefer not to experience.

But ACL injuries are quite common in sport and occur in all levels of play. They are most commonly seen in sports that involve sudden stops, changes of direction, jumping and landing – like football, rugby, basketball, and American football. Previous studies have shown ACL injuries to occur at a rate of 6.5 per 100 ,000 athlete exposures (any time an athlete engages in sporting activity). This might not seem like a lot, but athlete exposures within a single team can add up pretty quickly when you consider how many players there are and how many training sessions and games they participate in.

Unfortunately for female athletes, ACL injuries occur more regularly than men. Each year 20,000-80,000 female high school athletes sustain an ACL injury. In women’s domestic football, the knee is generally the most commonly injured body part, accounting for approximately 22% of all injuries. It’s been reported females are also eight times more likely to suffer an ACL injury than males – a pretty crazy statistic right? This is believed to be as a result of a number of anatomical, hormonal, and neuromuscular differences present in females.

Why do ACL injuries occur so often?

The ACL is clearly a problematic area within the sport and athletic circles, so it’s important to ask the question: Why do ACL injuries occur so often? The British Journal of Sports Medicine released a brilliant top five most played podcast series on this topic to try to explain and understand this in detail. In brief, a sudden twisting change of motion and high-force contact can cause the ligament in the knee to over-stretch, tear, and in some cases rupture completely. A good way to explain this in simple terms is to think of an elastic band. If you pull an elastic band in either direction or twist it with a little bit of force, then it will be okay. It will return to its baseline state of being a relaxed elastic band. However, if you overstretch or pull the elastic band in either direction with excessive force, then you may start to see small tears begin to appear. This tearing is very similar to what happens with the ligaments in the knee. Overstretching or pulling is not something these ligaments like, hence why tears appear – almost as a warning not to overdo it. However, in some cases, the force applied to the elastic band can be so strong and sudden that it completely snaps. The band can’t handle the force, and BOOM, it snaps away in your hand. This is the sound resembling the gunshot I referenced earlier.

Within the knee, it is the ligament that completely ruptures and shifts away from its stable starting position. I think you will agree, this does not sound enjoyable. Professor Keith Baar has to be one of the best researchers in this area and explains the injury mechanism well in these two videos here and here.

For many athletes, this injury signals the start of a lengthy recovery period of either rehabilitation without having surgery or, in most cases, preparing to go under the knife before beginning the rehabilitation process. Either way, it’s an interesting road ahead. To hear what a professional rugby player has made of it all, please read this article where England Rugby star Jack Willis speaks openly about his recovery from knee surgery.

The power of positivity during ACL rehabilitation

All is not doom and gloom, though, and it is important to remain positive during ACL rehabilitation. The recovery process is actually a great time to build resilience, character, and reflect on areas you can improve on once you are fully fit again.

The reason I know this is because I have experienced it myself. I won’t bore you with the details of how I sustained it, but I ruptured my ACL and suffered a significant tear in my meniscus a little while ago and can confirm it was quite painful and swollen! Funnily enough, it took me 10 months to realise I had sustained the injury, and in fact, carried on with my regular strength-based training, running 10km and even enjoyed skiing and snowboarding. Many athletes also continue with controlled and prescribed training before having surgery to repair their knee – the difference is, unlike me, they are generally aware of their injury!

As a performance nutritionist, I wanted to use myself as a mini project for a personal ACL and meniscus recovery case study. I re-read the key literature, listened to countless podcasts, and then applied the evidence and literature to my own personal nutritional strategies to recover from my surgery. Below I will link you to these key resources and explain how I did it.

ACL rehab: Phase 1, pre-surgery

Once I knew my surgery date, I had about four weeks to prepare myself before the surgeon worked their magic. I used this time wisely to reduce my fat mass slightly (increased cardio in the early mornings) and increase muscle mass on both legs. I followed a classic hypertrophy program for back squats and Romanian deadlifts and maintained a solid level of running. Additionally, I followed a high protein (2.5g/kg body mass) moderate carbohydrate (2-3g/kg body mass) nutritional strategy, consuming carbohydrates during and around training and reducing carbohydrate intake in the evening – essentially, fuelling for the work required. I also consumed creatine prior to surgery to support muscle mass growth.

In the final few days before surgery, I increased my creatine intake to 20 g per day for seven days to significantly increase my muscle creatine stores. I did this to try and minimise any muscle wastage that would occur once I had the operation. This was then reduced to 5 g per day post-surgery as a maintenance dose. I also prepared my surgery ‘care package’ before hitting the operating table. This care package contained food and supplements that I took into the hospital with me, ready for when I woke up from the operation (see below).

This care package included:

- Protein bars

- Collagen protein shots

- High omega-3 fish oil and protein drink

- Multivitamins, probiotics, omega-3 tablets

- Chewable vitamin C tablets

[optin-monster-shortcode id=”zmduwq9qz4orwfm5dng4″]

ACL rehab: Phase 2, post-surgery

Although hospital care nowadays is generally very good, I didn’t want to rely on the food provision at the clinic just in case it wasn’t quite as good as I needed it to be. Both the protein bar and repair shot provided me with a good quality source of both whey (~ 20 g) and collagen (~ 15 g) protein. You may think I am mad, but as soon as I woke from the operation, I consumed both supplements to begin the recovery and repair process. Alongside the protein, I swallowed the multivitamin, probiotic, omega-3 and vitamin C tablets. I think my nurse thought I had some kind of problem with the amount of supplements pills I had with me!

Although I habitually eat healthily in terms of lots of fruit and vegetables and try to achieve a rainbow a day of colours, I wanted to supply my body with a good multivitamin to support immune health, having just woken from surgery. The probiotic was to look after my gut, the omega-3 was to help reduce swelling and the vitamin C the same – to act as an antioxidant and reduce soreness and inflammation. I continued to take all four of these for the next six months. Another excellent product I consumed in the first few hours of waking up was an omega-3-enriched protein drink. Once again, this provided me with a good quality source of protein and 1.4 g of quality fish oil to help reduce the inflammation that surrounded my knee and upper thigh.

ACL rehab: Phase 3, home time, and the first 4-6 weeks

There is a lot to be said here about getting into a good routine and sticking to it. Once I was home, I set out a regimented plan of attack regarding specific feeding times and supplement schedules to help reduce the swelling as quickly as possible from a nutritional point of view.

Having previously had many Dual X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA – body composition assessment) scans as a student, I had access to data which would help me build an individualised nutrition strategy regarding total energy and macronutrient (carbohydrate, fat and protein) intake.

I used the commonly cited Cunningham equation ((lean body mass x 22) + 500) to work out my predicted resting metabolic rate (RMR). However, if you do not know your lean body mass or have access to finding it out, then you can use the following equation:

RMR (kcal.day-1) = 1254 + (9.5 x body mass in kg).

In simple terms, this equation is working out how many calories you normally burn in a 24-hour window. It does this by multiplying 9.5 x your body weight + 1254. so for me this would be 9.5 x 73kg = 693.5, then add 1254, so 693.5 + 1254 = 1947.5. Therefore my RMR is approx. 1947 calories per day.

My RMR is the total amount of calories I would need to maintain normal physiological function in a rested state. For me, this is around 1900-2000 kcal per day. However, considering my body had just come out of an operation, I knew it was going to take more calories than my RMR suggested, to support the fact my body was working overtime to recover, repair, and rebuild the soft tissue around the knee.

This is brilliantly shown in a case study on an English Premier League football player who, following an ACL operation, had a similar total energy expenditure to non-injured, fully active football players. The authors of this study said this similarity was due to the injured player working overtime to help repair and recover his body – pretty cool, huh?

It was therefore important I provided my body with ample calories from good-quality sources of nutrition rather than poor ones. For example, lots of fresh protein (i.e., oily fish, lean white meats, etc.), fruits, and vegetables, rather than sugary, fatty and pro-inflammatory foods.

The increase in calories mainly came from protein, as I tried to maintain a total intake of around 3 g per kg of body weight (approx. 210 g). When I was awake, I maintained protein distribution throughout the day to every 2-3 hours (i.e., 20-30 g of protein, consumed every 2-3 hours), in line with key literature. You may laugh, but for the first few days, I set my alarm for every three hours to remind me to down my next source of protein. After a few days, my internal alarm was set, and I had formed a habit that had stuck well. This habit-forming was born from inspiration from reading Atomic Habits by James Clear – a brilliant book, and I would highly recommend it to anyone reading this blog.

Another supplement I added was vitamin D3. As I had my operation in October (Autumn time in the UK), and I was pretty much immobile, so my access to daily sunlight was limited. I had a good guess I was not going to see much sunlight for a few weeks, and even if I did, the sun was not going to be strong enough to give me a natural dose of vitamin D3. That’s why I opted for the supplement throughout the winter months and took one tablet per day for the next six months.

The secret of prepped meals

Now, anyone who has been on crutches for a period knows how difficult it is to get around the house. More specifically, how hard it is to try and cook in the kitchen whilst hobbling around like Captain Jack Sparrow after one too many rums. I didn’t want to put myself through this struggle, so I decided to invest in a prepped meal company to make it easier for me. I was able to pick specific meals out and if I needed to adjust the macronutrients of each meal, it was as easy as customising my order. Investing in pre-made meals really was a great choice – all I had to do was put them in the microwave for two minutes, and I knew I had a good-quality meal ready to go.

Before we move on, I just wanted to summarise and share in brief my rough nutritional intake day to day. Please see below:

Breakfast

3 eggs with peppers and onion

1 slice of rye bread

1 repair shot

1 Whey protein with creatine and glutamine

1 multivitamin

1 omega 3

1 probiotic

1 vitamin D3

Snack

1 Greek Yoghurt with mixed berries

1 Whey shake

Lunch

1 Prepped meal – 30 g of lean chicken, 40 g of brown rice and fresh vegetables

1 repair shot

Snack

1 Enhance Recovery sports drink

1 piece of whole fruit

Dinner

1 Prepped meal – 30 g of lean turkey, 40 g of brown pasta and fresh vegetables

Pre-bed

1 repair shot

1 Whey protein with creatine and glutamine

ACL rehab, Phase 4: Progression and return to exercise

Following the first few weeks, my knee was feeling great and I was progressing well with exercises. My timeline was pretty much what you would expect for an ACL recovery and meniscus repair (i.e., 1-4 weeks reducing inflammation, 4-8 weeks beginning mobility and light exercise).

I continued with the nutritional strategy outlined above, and on days when my exercise increased, I slightly increased the fuel I consumed too. To be honest, there wasn’t really a period where I shied away from nutritional intake, which I have seen in some athletes. It is not uncommon to hear athletes “not eating enough” or quickly losing weight because they are undereating. I was actually the opposite – I was purposely overeating but with good-quality calories.

My physiotherapist was happy with my progress, and at 13 weeks post-operation, I ran 5km in 26 minutes which is a pretty great time considering what I had been through (a good 5km time is anywhere near 25 minutes). This was a brilliant day – a day where I genuinely felt proud of myself for sticking to a good routine with nutrition. Importantly, this wasn’t just nutrition off the cuff – I was reading the literature and applying it to myself to prove that it works. It is possible – you can return to exercise in a considerably quick time post-op with the help of nutrition.

Since that day, I have run every week and resumed all my strength training again.

Some final food for thought

Although suffering an ACL injury is harsh for any athlete, it doesn’t have to be a negative experience. I found myself really enjoying the different stages of rehab and experiencing first-hand how important nutrition can be to nail a quick return to exercise. I did not have access to a physio every day as a professional athlete would, but one thing I did have access to was a good-quality nutritional strategy.

I was convinced reading the correct literature and applying it to myself would result in a strong outcome for the project. It made me think about how many athletes who suffer an injury potentially switch off and become demotivated as a result. How many of them think “ah, screw it” and turn to sweets, chocolate, and fast food as a way of comforting themselves for a few days.

I can confidently say I hit 90-95 % of my nutritional strategy consistently day to day. I didn’t consume fast food or snacks, which were going to promote inflammation and delay recovery. Of course, I had the odd low-calorie ice cream or sweet, but really stayed committed to keeping it focused throughout. If you are going to snack on something a little naughty, just make sure it is not a daily occurrence!

My advice for anybody who has either suffered an ACL injury or is about to go into surgery for another soft tissue injury would be to sit down with a registered nutritionist or dietician and work on a bespoke nutritional strategy that is both achievable and enjoyable for you to follow. Although you may not think nutrition plays a pivotal role in the recovery from surgery, I can tell you first-hand that the reason I am running a half-marathon 10 months post-operation is due to a solid evidence-based nutrition strategy.