Contents of Article

- Summary

- What is agility?

- Why is agility important for sports?

- What are some examples of agility exercises?

- How do you measure agility?

- Are there any issues with measuring agility?

- Is future research needed on agility?

- Conclusion

- References

- About the Author

Summary

Agility in sport is defined as ‘‘a rapid whole-body movement with change of velocity or direction in response to a stimulus’’ (Sheppard, 2005). Meaning agility must involve a reaction to a stimulus, for example, a goalkeeper reacting and saving a penalty kick in football.

Though the terms ‘agility’ and ‘change of direction speed’ are often used interchangeably, recent knowledge has distinctively separated the two. Put simply, agility involves reactive abilities in unpredictable environments, whilst change of direction speed focuses purely on physical ability and is typically performed in pre-planned environments. This infers that traditional agility tests (e.g. t-test and pro-agility) are not actually capable of measuring agility, and thus should be referred to as change of direction speed tests.

Recent research has shown that higher-level athletes perform better on agility tests than lower-level athletes, but the same does not apply to change of direction speed tests.

What is agility?

In a nutshell, Agility is ‘‘a rapid whole body movement with change of velocity or direction in response to a stimulus’’.

Over the past several decades, ‘agility’ appears to have been referred to as almost anything that requires an athlete to quickly change direction multiple times. As a prime example, the T-test, Illinois agility test, arrowhead agility test, and pro-agility test have all historically been referred to as agility tests, simply because they require an athlete to complete a pre-planned course of directional changes as quickly as possible. However, it is important to understand from hereinafter these tests are not actually a measure of agility, but instead a measure of ‘change of direction speed’.

Agility has been a topic of large discussion in recent years and has led to several experts attempting to clearly define it. Perhaps the best current definition of agility is that proposed by Sheppard and Young (2005) (1):

Agility is ‘‘a rapid whole body movement with change of velocity or direction in response to a stimulus’’.

The fundamental words to remember in that definition are “in response to a stimulus”. It is this fragment of the definition that separates a “true” agility test, from a simple change of direction speed test (e.g. pro-agility test) – thus, agility contains a reactive component. This reactive component is built up of many cognitive functions (1) such as:

- Visual processing

- Timing

- Reaction time

- Perception

- Anticipation

It is the absence of these cognitive functions during traditional agility tests (e.g. t-test) that means they are in fact simply change of direction speed (CODs) tests. The difference between agility and CODs is not just semantics, they are completely different performance qualities which only have a small relationship with one another, if any (2, 3, 4).

For example, a defender’s reaction to an attacker’s sudden movement would be classified as an agility-based movement, as it requires them to make a reactive decision based upon the attacker’s impulsive movement. In contrast, when an athlete is instructed to run through a planned arrangement of cones (e.g. T-test), then the reactive component is removed and it is purely an example of their CODs.

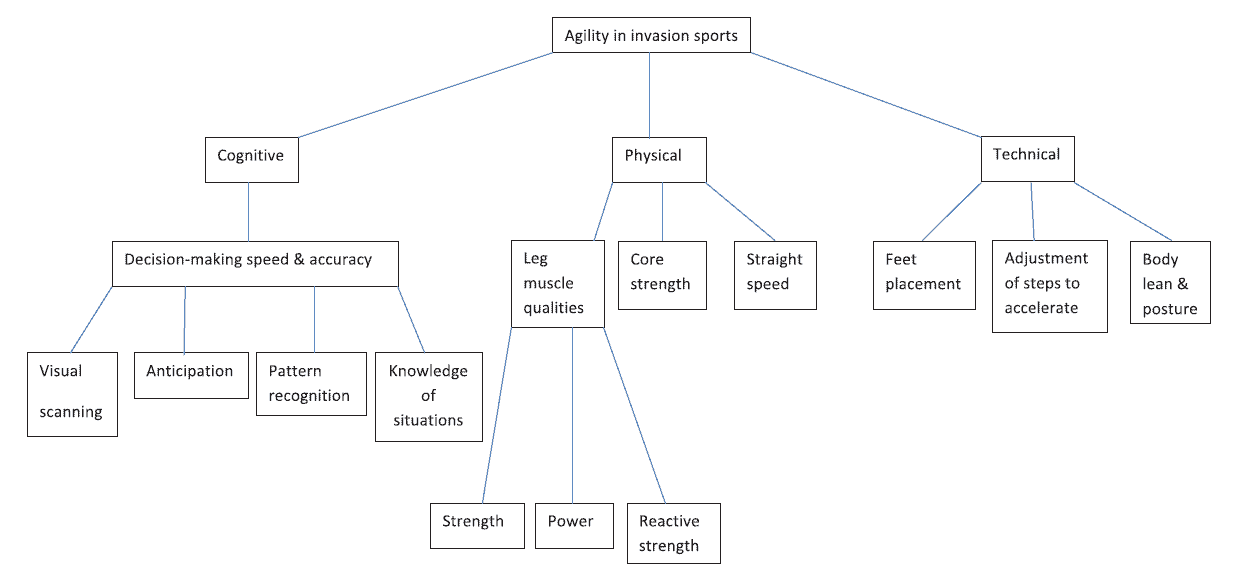

Though agility requires the use of cognitive components, it is also composed of other qualities – namely ‘physical’ and ‘technical’. It is these several qualities (cognitive, physical, and technical) which have been said to collectively form agility (Figure 1). This combination of independent qualities, plus the unplanned nature of agility, means agility has been referred to as a complex and open motor skill in its own right (5).

Why is agility important for sports?

Agility is vital for successful performances in most sports (6). Take invasion/territorial sports (e.g. football, rugby, hockey, and American football) for example, whereby the objective of each team is to invade the opposition’s area in an attempt to score a point(s). In these sports, the defending teams are attempting to win possession of the ball by tackling the opposition or forcing errors. Consequently, the attacker aims to avoid tackles, retain possession, and create scoring opportunities. To prevent the attacking team from scoring, the defenders must continuously ‘anticipate’ and ‘react’ to the attackers’ movements.

To do this successfully, the defenders must use the cognitive functions listed above which are all components of agility. For example, if an attacker attempts to suddenly accelerate past the defender, the defender must have a fast reaction time to prevent this from happening. This demonstrates only one very simple match-play-related agility movement but exhibits the use of agility nonetheless.

Interestingly, higher-level athletes have been shown to perform better on agility tests than lower-level athletes (3, 4, 7, 8, 9). This indicates that improving an athlete’s agility may be very important if they wish to progress and compete at a higher level in their sport. Furthermore, unlike agility tests, higher-level athletes do not perform better on CODs in comparison to lower-level athletes – suggesting that CODs may not be as important for athletes as agility.

What are some examples of agility exercises?

The video below shows some great examples of speed and agility exercises specifically for American Football. It is important to notice the athletes begin with a session-specific warm-up, then they move into ‘pre-planned’ change of direction drills before finally moving into some reactive agility drills. The reactive agility exercises are when the coach initiates movements with his arms that the athletes must respond to by changing direction.

How do you measure agility?

As recent knowledge has identified that agility contains a cognitive component, then traditional methods of measuring agility (e.g. t-test, pro-agility test and the Illinois test) unfortunately fail to do so. Instead, these traditional tests which are only capable of measuring CODs should be replaced with innovative new tests that can measure agility. This has led to the development of several new agility tests such as:

- Reactive agility test – Rugby league (3, 8)

- Reactive agility test – Netball (6)

- Reactive agility test – Australian rules football (10, 11)

- Stop’n’Go reactive agility test (12)

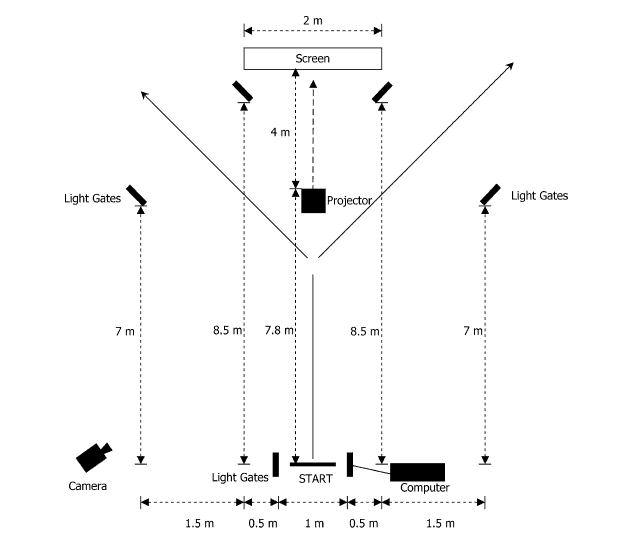

The top three tests (reactive agility tests) all use a Y-shape configuration (Figure 2) with a projector/screen which plays video clips of an athlete performing some form of movement, it is this sudden movement that the athlete being tested must react to. These tests, therefore, require the athlete to change direction in response to a stimulus whilst moving at high speed.

Though traditional “planned” agility testing may not be capable of measuring agility, it may still play a useful role in the testing battery. The following table (Table 1) adapted from Bruce et al. (2004) (13) demonstrates how performance can be broken down to further identify the athlete’s strengths and weaknesses.

| Athlete | Planned Total Time (s) | Reaction Total Time (s) | Decision Time (ms) | Diagnosis/Decision |

| A | 3.10 | 3.69 | 120 | Has speed, but slow decision time contributes to below-average reactive performance. Needs more decision-making drills on- and off-court. |

| B | 3.75 | 3.20 | -160 | Perceptually skilled, but lacks pure change of direction speed. More speed/agility work required to improve physical attributes. |

| Average time | 3.30 | 3.50 | -60 |

Are there any issues with measuring agility?

Though new tests have been developed that include a reactive stimulus, there is still uncertainty regarding the use of some of these tests. These uncertainties remain despite them being deemed both valid and reliable. Some of these uncertainties are:

- When a light or sound stimulus is used instead of a video, does that accurately measure an athlete’s ability to react to a sport-specific stimulus (e.g. an opponent changing direction)?

- When testing, if only 10 video clips can be used for reliability purposes, then is there a learning curve for the athlete being tested – i.e. have they seen that clip before and thus can react faster?

- If the only stimulus is in front of the athlete during testing, then does this negate any peripheral reaction skills?

- If the reaction stimulus is only a player side-stepping, then does this truly account for the various other stimuli that an athlete may encounter during training or competition?

Is future research needed on agility?

Given our advancements in the understanding of agility, future research should be directed towards some of the following:

- The development of sport-specific agility tests.

- The possibilities of dual-response stimuli instead of the current single-response stimuli tests.

- Relationships between physical qualities (e.g. reactive strength and relative strength) and agility and/or CODs performances.

- Biomechanical/technical differences or even weaknesses when an athlete has to respond to a stimulus? In other words, do faulty mechanics become evident in a reactive environment?

Conclusion

- Agility contains a reactive component.

- Traditional agility tests (e.g. t-test, Illinois, pro-agility test etc) do not measure agility, and thus from here on should be referred to as change of direction speed (CODs) tests.

- Agility performances can distinguish between higher- and lower-level athletes.

- Testing CODs may still be a useful tool during performance testing to identify strengths and weaknesses.

- Research into the aforementioned areas should substantially advance current practices.

- Sheppard JM, Young WB. (2005). Agility literature review: classifications, training and testing. J Sports Sci. 2006 Sep;24(9):919-32. [PubMed]

- Scanlon, A., Humphries, B., Tucker, P.S. and Dalbo, V., The Influence of Physical and Cognitive Factors on Reactive Agility Performance in Men Basketball Players, Journal of Sports Sciences, 2013, 32(4):367-74 [PubMed]

- Gabbett, T.J., Kelly, J.N. and Sheppard, J.M., Speed, Change of Direction Speed, and Reactive Agility of Rugby League Players, Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2008, 22, 174-181. [PubMed]

- Sheppard, J.M., Young, W.B., Doyle, T.L.A., Sheppard, T.A. and Newton, R.U., An Evaluation of a New Test of Reactive Agility and its Relationship to Sprint Speed and Change of Direction Speed, Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 2006, 9, 342-349. [PubMed]

- Jeffreys, I. (2006). Motor Learning — Applications for Agility, Part 1. National Strength and Conditioning Association. 28(5). pp.72–76. [PubMed]

- Young WB, Dawson B, Henry GJ. Agility and Change-of-Direction Speed are Independent Skills: Implications for Training for Agility in Invasion Sports. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 2015, 10(1). 159-169 [PubMed]

- Henry, G., Dawson, B., Lay, B. and Young, W., Validity of a Reactive Agility Test for Australian Football, International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2011, 6, 534-545. [PubMed]

- Serpell, B.G., Ford, M. and Young, W.B., The Development of a New Test of Agility for Rugby League, Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2010, 24, 3270-3277. [PubMed]

- Young, W., Farrow, D., Pyne, D., McGregor, W. and Handke, T., Validity and Reliability of Agility Tests in Junior Australian Football Players, Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2011, 25, 3399-3403. [PubMed]

- Veale JP, Pearce AJ, and Carlson JS. Reliability and Validity of a Reactive Agility Test for Australian Football. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2010, 5, 239-248 [PubMed]

- Young WB and Wiley B. Analysis of a reactive agility field test. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 2009; 13(3):376-8. [PubMed]

- Sekulic, D, Krolo, A, Spasic, M, Uljevic, O, and Peric, M. The development of a new stop’n’go reactive-agility test. J Strength Cond Res 28(11): 3306–3312, 2014. [PubMed]

- Bruce L, Farrow D, Young WB. Reactive Agility: The Forgotten Aspect of Testing and Training Agility in Team Sports. Unpublished. [PubMed]