Contents of Article

- Summary

- What is early specialisation?

- What are the issues associated with early specialisation?

- What are the potential benefits of early specialisation?

- How do you monitor early specialisation?

- What alternatives are there to early specialisation?

- Is future research needed with early specialisation?

- Conclusion

- References

- About the Author

Summary

Early sports specialisation is a concept related to children which is defined as an intense and specific focus on one sport at the exclusion of others [1]. This is driven by the belief that selecting one sport and excluding others will increase the likelihood of athletic success. There remains concern that engaging in a year-round, concentrated programme in a single sport can negatively impact both physical and psychological health.

This may be driven by society’s increased regard for successful athletes, who can experience social recognition, scholarships, sponsorships, and financial reward for competing at a high level. Whilst the definition of early sports specialisation remains uncertain, the general consensus suggests that intense and selective participation in one sport could lead to several issues associated with overuse and burnout [2].

What is early specialisation?

Entrance into academies or clubs with high prestige is often regarded as an important requirement for young athletes, exposing them to a high level of coaching, opportunities, and an increased likelihood of success. This, combined with the idea that the best way to achieve elite-level status in sports is through single-sport participation alone, drives many of the issues associated with early specialisation. Such an approach can limit the development of an individual, by preventing the transfer of skills that may have otherwise been developed by participating in other sports.

In research, early specialisation is defined as participating in a single sport, with a deliberate focus on training and development in one sport only [3]. To communicate this more effectively, early specialisation may be described as [4]:

- Choosing to participate in one sport.

- Participating in this sport for greater than eight months per year and;

- Quitting other sports to focus on just one.

For most sports, intense training in one sport at the exclusion of others should be delayed until middle to late adolescence [5]. This approach minimises the likelihood of injury and psychological stress whilst youth are going through both growth and academic pressure.

Sports specialisation can also be associated with an increased risk of burnout, social isolation, and possible dropout from sport at an early age [1]. As a result of early sports specialisation, youth can be deprived of year-round sports development which can lead to a loss of motor skill acquisition and opportunities for fun and focused physical activity, both of which are important for career longevity and general health and wellbeing.

What are the issues associated with early specialisation?

Although some degree of specialisation is required during childhood/adolescence, the timing and amount of single-sport participation remains controversial. Highly focused physical training and the accompanying levels of competition expose athletes to both physical and psychological stresses that are often excessive and unnecessary [6]. In the short term, a child may tolerate and even benefit from such a routine over their peers. However, the long-term implications can be devastating for an individual’s health and enjoyment of sport.

Issues associated with early specialisation can manifest in several ways and can be acute (happen suddenly), or chronic (occur over time). Becoming a successful elite athlete is virtually impossible without performing close to one’s performance limit in both training and competition over extended periods of time. This can, however, place a large physical load on the body.

One of the most common concerns presents itself in the form of overuse injuries, where training errors, technical errors, or the simple act of repetitive movements (e.g. passing a ball with a certain foot) can lead to imbalances or injuries. In high/secondary schools, overuse injuries account for 46-50% of all athletic injuries [7]. Over time, these can become devastating for sports participation and can impact an athlete’s personal life, career, and comfort.

An effective and safe method to reduce this injury risk can be achieved by allowing children to engage in youth strength training, where supervised and progressive practice can strengthen key muscles, bones, and tendons.

In response to early specialisation, the bones during adolescence are more susceptible to issues such as breaks and fractures. This increased risk may be related to a number of factors, but are mainly due to the diminished size-adjusted bone, weakness of the growth cartilage, and decreased physical tolerance [9]. Furthermore, bones experiencing rapid growth as a result of maturation are less resistant to tensile, shear, and compressive forces than their adult or prepubescent counterparts, resulting in an increased risk of potential fractures or breaks [6]. The long-term impact of this can result in early onset osteoporosis, joint instability, and decreased function [6].

During adolescence, psychological challenge is essential to provide both positive responses and the capacity to generate appropriate coping strategies for the stresses of daily life and sport. In competitive situations, excessive travel, academic stress, and pressure to succeed may lead to psychological overload. Unrealistic expectations placed on oneself, by a parent, or coach, may lead to low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, and potential burnout [6].

Over time, these individuals can withdraw from sport and feel isolated by a routine that has so far limited their opportunity to develop an identity with their peers or social norms. As a result of this, daily life can prove challenging and children can perceive a lack of control over their lives, believe they have fewer chances for autonomy, and possess low levels of motivation to train [6].

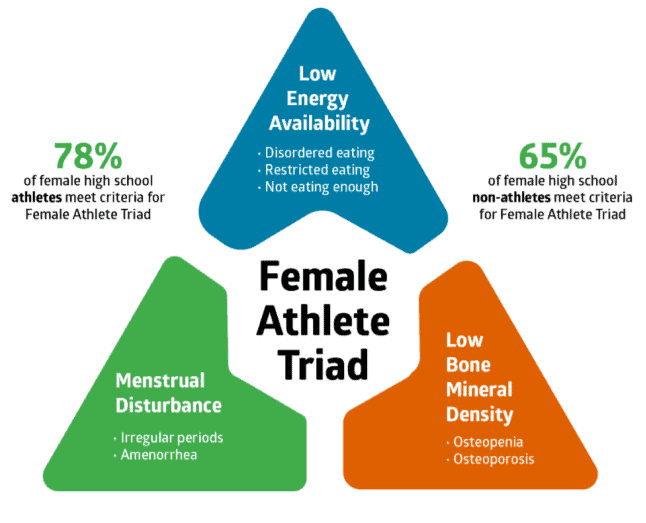

In physically active girls and women, early sport specialisation has been identified as a major contributor to a medical condition known as the female athlete triad (See Figure 1). The female athlete triad describes three interrelated components of health, where it is shown that highly voluminous sports training and inadequate energy intake can lead to alterations in energy availability, menstrual cycle function, and bone mineral density (BMD) [9].

Female athletes who specialise in disciplines which require body leanness or endurance such as; endurance running, gymnastics, dancing, and figure skating are particularly vulnerable [6]. The long-term effects of this can be devastating, placing an individual at an early risk of osteoporosis, disordered eating, and amenorrhea described as an abnormal menstrual cycle [9].

What are the potential benefits of early specialisation?

Whilst specialising early in a sport has not been shown to improve the likelihood of sports success [1, 2], there may be some inherent benefits of doing so. Early participation in sports can foster behaviours such as punctuality, cohesiveness, hierarchy, and knowledge. All of which can help an individual to conform to the standards expected of academies quicker. In turn, this can lead to individuals being selected by coaches as they perceive them to be a low investment individual who understands the cultural norms and behaviours required in that sport.

When choosing to specialise early, players experience increased contact time with coaches which can lead to greater acute skill development. In the short-term or in sports trials, this may place a player in greater stead who has received a higher level of coaching and may be represented in the form of positional sense, movement skill, self-confidence and worth, or formation knowledge, thus increasing the likelihood of impressing coaches and being selected. This becomes more important in sports such as gymnastics or figure skating, where athletes from as young as 12 can represent their country nationally and internationally [10].

How do you monitor early specialisation?

With overuse injuries and burnout being strongly associated with early specialisation, monitoring these through conversations with the athlete, rate of perceived exertion (RPE) data, injury history, and multidisciplinary approaches with coaches/parents may be the best way of observing any changes that could be concerning. This is particularly important in children who participate for more than 16 hours per week in intense training [2], which can lead to overuse injuries or decrements in performance due to overreaching or overtraining. Furthermore, subtle nutrition interventions may prove useful, allowing athletes to understand the relationship between energy intake and outtake under qualified assistance/instruction to combat the female athlete triad.

As mentioned, early specialisation places a large physical load on the body which is exacerbated by repeated movement. During periods of growth, including Peak Height Velocity, an excessive physical load can lead to injury which may be prevented by growth monitoring.

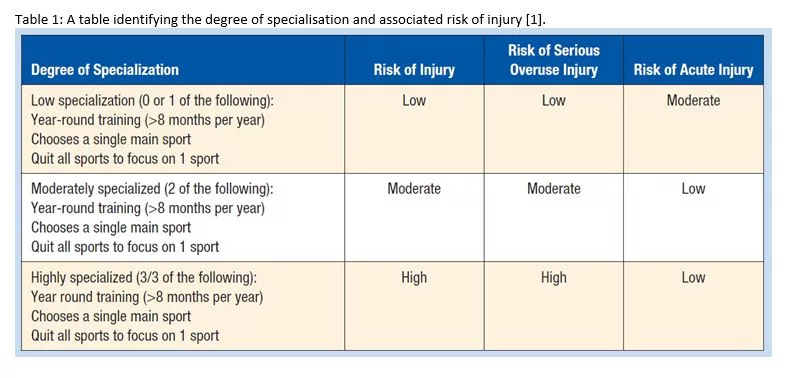

Note: A full description of what growth monitoring is and a FREE calculator for tracking is available here. This free tool can be used to guide the volume of training and prevent your athletes’ injuries. Finally, a simple tool for identifying those at risk from early specialisation can be seen in Table 1, drawing a relationship between specialisation and the likelihood of developing an injury [1].

What alternatives are there to early specialisation?

Alternative solutions to early sports specialisation may appear obvious. Limiting the amount of time in one sport and exploring a diverse range of varied sports may be the solution known as ‘early diversification’ [11]. This approach favours a long-term athletic development methodology, viewing the growth of an athlete as a process that requires time and patience. The benefits of early diversification include experiencing different sporting environments, which, in return, allows an individual to develop the physical, cognitive, and affective behaviours to specialise later in a career [7].

Furthermore, increasing the hours of ‘deliberate play’, defined as either intentional or voluntary sports games (such as playing with your friends in a park) ensures children have fun and are less likely to drop out of sports at a later age [7]. By participating in deliberate play, athletes can experience a shift in the emphasis from strictly winning, to skill development, trial and error, and enjoyment.

Early specialisation remains a sociocultural issue, anchored deep In Western and Eastern civilisation [12]. Working with purpose, effort, and focus is often associated with success in any discipline and naturally lends itself to the sports environment. This can be driven by parents, who may be responsible for channelling their own interests and hobbies onto their children, forcing them to concentrate on one area of development, and overemphasising the importance of sporting achievement [12]. As a result, children may misbehave, be disinterested, or display unruly behaviour in environments outside of sport [12].

Despite decades of research addressing the issues with early specialisation, sports academies have not always followed guidelines, encouraging youth to be hard-working, robust, and loyal to a fault. This “commodity-based” approach is damning for the industry and relatively short-sighted, limiting sports career longevity and the height of one’s performance ceiling. Therefore, it should be the responsibility of academies to educate children and parents on the benefits of rounded sports participation, with this long-term approach facilitating more movement-literate athletes to mould. This may be an area for improvement, where collaboration with parents, teachers, and external clubs should be encouraged to understand the volume of training per week, allowing for alterations in training intensity. Regrettably, a multidisciplinary approach can be limited by poor resources, contact time, pressure for results, or inadequate athletic vision making this a constant challenge.

Driving a child’s pursuit of a sports career are teachers and coaches who “label” children as talented in a sport from a young age. These can be responsible for motivating both participation and efforts in one sport, in the absence of total athletic development. The above, coupled with the pursuit of an athletic scholarship, sponsorship, or specific clothing/facility demands (i.e. a basketball arena promotes only basketball), can also be contributing factors to early specialisation.

Bottom-up or top-down, future education is key to empowering and educating all of these sources, driving home the message that more is not always better, and that being a “master of one and jack of none” continues to drive injury and burnout from childhood to middle-adolescence [6].

With appropriate strength and fitness conditioning, the risk of sports-related injury can be reduced given that equipment is child-sized and planned and monitored by a qualified coach/sports scientist [6]. When choosing an academy/club with prestige, investigating the focus on fundamental movement skills (FMS), defined as the building blocks of athleticism is key [13]. These should not only be a priority but a key addition to training in children between the ages of 6-12 in any sport [13].

Fortunately, some academies do take the holistic development of their athletes seriously, prioritising their development of FMS and behavioural skills alongside their focused sport [14]. As children enter the later stages of development (14-17 years old), layering elements of sport-specific activities, conditioning, and behavioural expectancies build compliance and support the transition into professional sport by exploiting the athlete’s increased maturity and focus with age [13].

Is future research needed with early specialisation?

Early specialisation is a highly complex and individual phenomenon, with a ‘diagnosis’ or identification scheme yet to enter grassroots sports. Some interesting areas and directions for future research may include:

- Understanding the volume-injury-related relationship in youth sports.

- Supporting initiatives that educate and empower parents, coaches, and athletes, to identify with the symptoms and issues associated with early specialisation.

- To understand the training ratios required for sports success, support practitioners with practical examples of how specialisation and diversification could work together.

- Exploring Long-Term Athletic Development (LTAD) and the financial, reputable, or external pressures placed upon coaches to generate talent; forcing the hand on specialisation.

Conclusion

Early specialisation continues to be both a challenging and frustrating nemesis for parents, coaches, teachers, and children. Early specialisation may affect various components of health, including nutrition, maturation timing, bone health, muscle imbalances, psychological stress and career longevity [2, 6, 11]. Those who do manage to “survive” early sports specialisation and train rigorously from a young age may benefit from exceptional anatomical and psychological profiles [15].

As coaches, practitioners, parents, etc., we must continue to read, educate, and understand the growing constraints of sport in order to deliver solutions that are sustainable and realistic over the long term.

- Myer, G.D., Jayanthi, N., Difiori, J.P., Faigenbaum, A.D., Kiefer, A.W., Logerstedt, D. and Micheli, L.J., 2015. Sport specialization, part I: does early sports specialization increase negative outcomes and reduce the opportunity for success in young athletes?. Sports Health, 7(5), pp.437-442. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1941738115598747

- Román, P.Á.L., Pinillos, F.G. and Robles, J.L., 2018. Early sport dropout: High performance in early years in young athletes is not related with later success. Retos: nuevas tendencias en educación física, deporte y recreación, [33], pp.210-212. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6367755

- Baker, J., 2003. Early specialization in youth sport: A requirement for adult expertise?. High ability studies, 14[1], pp.85-94. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Joe_Baker/publication/251213541_Early_Specialization_in_Youth_Sport_A_requirement_for_adult_expertise/links/0deec53615014c5520000000/Early-Specialization-in-Youth-Sport-A-requirement-for-adult-expertise.pdf

- Myer, G.D., Jayanthi, N., Difiori, J.P., Faigenbaum, A.D., Kiefer, A.W., Logerstedt, D. and Micheli, L.J., 2015. Sport specialization, part I: does early sports specialization increase negative outcomes and reduce the opportunity for success in young athletes?. Sports Health, 7[5], pp.437-442. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1941738115598747

- Lloyd, R.S. and Oliver, J.L. eds., 2013. Strength and conditioning for young athletes: science and application. Routledge. https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=rXIdAAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP2&dq=5.%09Lloyd,+R.S.+and+Oliver,+J.L.+eds.,+2013.+Strength+and+conditioning+for+young+athletes:+science+and+application.+Routledge.&ots=kQ-0zEk0zW&sig=RmeSvhK-TG51g3Ttfl3cMowyKnc

- Blagrove, R.C., Bruinvels, G. and Read, P., 2017. Early Sport Specialization and Intensive Training in Adolescent Female Athletes: Risks and Recommendations. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 39[5], pp.14-23. https://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/Fulltext/2017/10000/Early_Sport_Specialization_and_Intensive_Training.3.aspx

- Brenner, J.S., 2016. Sports specialization and intensive training in young athletes. Pediatrics, 138[3], p.e20162148. https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/138/3/e20162148.abstract

- Savard, K., Theriault, C., Weinstein, P. and Zerpa Calderon, M., 2018. Female Athlete Triad: Presentation. https://dune.une.edu/pt_studadmin/4/

- De Souza, M.J., Nattiv, A., Joy, E., Misra, M., Williams, N.I., Mallinson, R.J., Gibbs, J.C., Olmsted, M., Goolsby, M. and Matheson, G., 2014. 2014 Female Athlete Triad Coalition Consensus Statement on treatment and return to play of the female athlete triad: 1st International Conference held in San Francisco, California, May 2012 and 2nd International Conference held in Indianapolis, Indiana, May 2013. Br J Sports Med, 48[4], pp.289-289. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/48/4/289?itm_campaign=bjsm&itm_content=consumer&itm_medium=cpc&itm_source=trendmd&itm_term=0-A

- Law, M.P., Côté, J. and Ericsson, K.A., 2007. Characteristics of expert development in rhythmic gymnastics: A retrospective study. International journal of sport and exercise psychology, 5(1), pp.82-103. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1612197X.2008.9671814

- Baker, J., 2003. Early specialization in youth sport: A requirement for adult expertise?. High ability studies, 14(1), pp.85-94. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1612197X.2008.9671814

- Malina, R.M., 2010. Early sport specialization: roots, effectiveness, risks. Current sports medicine reports, 9(6), pp.364-371. https://journals.lww.com/acsm-csmr/Fulltext/2010/11000/Early_Sport_Specialization__Roots,_Effectiveness,.14.aspx

- Woods, C.T., McKeown, I., Keogh, J. and Robertson, S., 2018. The association between fundamental athletic movements and physical fitness in elite junior Australian footballers. Journal of sports sciences, 36(4), pp.445-450. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02640414.2017.1313996

- Ryan, D., Lewin, C., Forsythe, S. and Mccall, A., 2018. Developing World-class Soccer Players: An Example of the Academy Physical Development Program From an English Premier League Team. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 40(3), pp.2-11. https://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/Fulltext/2018/06000/Developing_World_Class_Soccer_Players__An_Example.2.aspx

- Capranica, L. and Millard-Stafford, M.L., 2011. Youth sport specialization: how to manage competition and training?. International journal of sports physiology and performance, 6(4), pp.572-579. https://journals.humankinetics.com/doi/abs/10.1123/ijspp.6.4.572