Contents of Article

- Summary

- How do ACL injuries occur?

- What is the Landing Error Scoring System (LESS)?

- Why is the Landing Error Scoring System useful?

- How do you conduct the Landing Error Scoring System?

- How do you score the Landing Error Scoring System?

- Is the Landing Error Scoring System valid and reliable?

- Conclusion

- References

- About the Author

Summary

First presented in 2009, the Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) is a clinical tool used to assess jump-landing biomechanics. It was developed to identify individuals at risk of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury (20) and is performed with a subject completing a Drop-Vertical Jump (DVJ) whilst video recorded from two planes (frontal and sagittal) (17). Being an easier, faster, and cheaper field-based variant of a complete biomechanical assessment (19), it can be performed without expensive laboratory equipment.

How do ACL injuries occur?

Despite the explosion of research on ACL injury during the last 30 years, the exact mechanism of injury is still not fully understood. However, a combination of internal (e.g. anatomic, hormonal, neuromuscular) and external factors (e.g. environment, footwear, ground, opposing players) may adequately explain the mechanism (8, 11).

The greatest strain on the ACL occurs during three-dimensional knee loading, which includes a knee extension moment, proximal anterior tibial shear force, knee valgus/varus moment, as well as a rotational contribution (18). After ACL reconstruction, altered movement mechanics in jump-landing tasks are often apparent (11) and have been shown to increase the risk of re-injury by 5-15 fold (10).

Focussing on particular movements that have been associated to ACL injury during landing tasks (11), such as valgus rotation at the knee joint, movements screens such as the LESS have been developed to identify athletes who may be at risk of sustaining an ACL injury (20).

What is the Landing Error Scoring System (LESS)?

The Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) is a relatively easy-to-use assessment tool to analyse the biomechanics of the lower extremities in a landing and jumping task. As a reliable clinical screening tool, it is described to offer the greatest value for the identification of individuals at risk of attaining non-contact ACL injury (20). However, recent research has questioned its ability to identify those at risk of ACL injury due to a lack of validity (9).

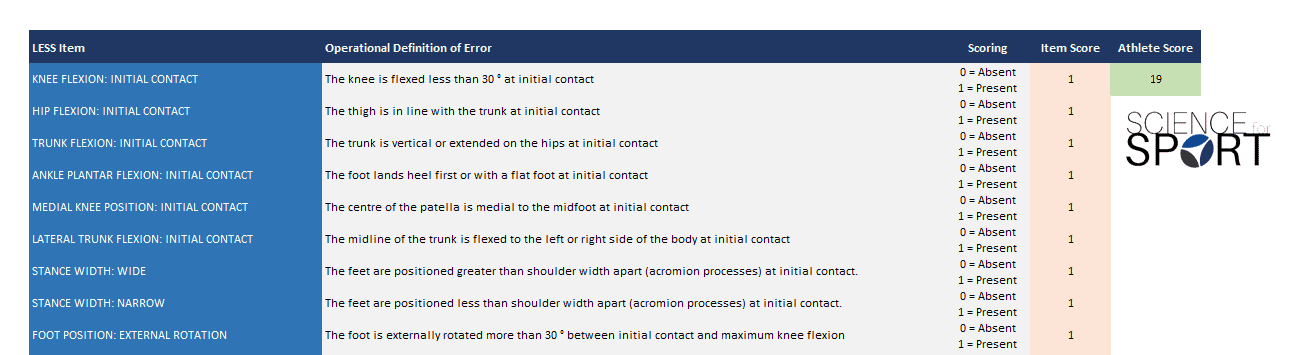

Based on a 19-point continuous scale (see FREE downloadable scoring sheet), the LESS assesses the positioning of the trunk and lower extremities at various stages through the Drop-Vertical Jump (DVJ) movement. Global fluidity and range of motion in the landing phase are analysed from frontal and sagittal plane video data. Movement patterns deviating from the ‘biomechanical optimum’ can possibly predispose an athlete to lower-extremity injuries (14). Those are scored as “error points”, and add up to a LESS score.

Poor landing technique is indicated by higher LESS scores (more “error points”) and vice versa.

Why is the Landing Error Scoring System useful?

As mentioned above, it is important to assess movement patterns that may predispose an athlete to ACL injury. As such, the LESS offers an accurate and inexpensive assessment of these movement concerns. Athletes identified as ‘at risk’ can then be directed towards specific training programmes designed to improve jump-landing mechanics in an attempt to reduce their risk of ACL injury.

Having said this, recent research assessing the effectiveness of the LESS for identifying ACL injury risk concluded it had limited predictive ability (8). This also lies in the generally low sensitivity and specificity of screening methods to this day.

It might be wishful thinking to try to predict future injuries in an otherwise healthy athlete (1). Movement screens cover just a small part of the ACL injury mechanism, most other factors cannot be screened for.

How do you conduct the Landing Error Scoring System?

It is important to understand that whenever fitness testing is performed, it must be done in a consistent environment (e.g. facility) so it is protected from varying weather types, and with a dependable surface that is not affected by wet or slippery conditions. If the environment is not consistent, the reliability of repeated tests at later dates can be substantially hindered and result in worthless data.

Required Equipment

- Consistent testing facility (e.g. gym or laboratory)

- Measuring tape

- Box: 30cm height

- Marking tape/sports tape

- Two off-the-rack video cameras (including a tripod/stand)

- Performance recording sheet (see FREE downloadable content)

Test Configuration

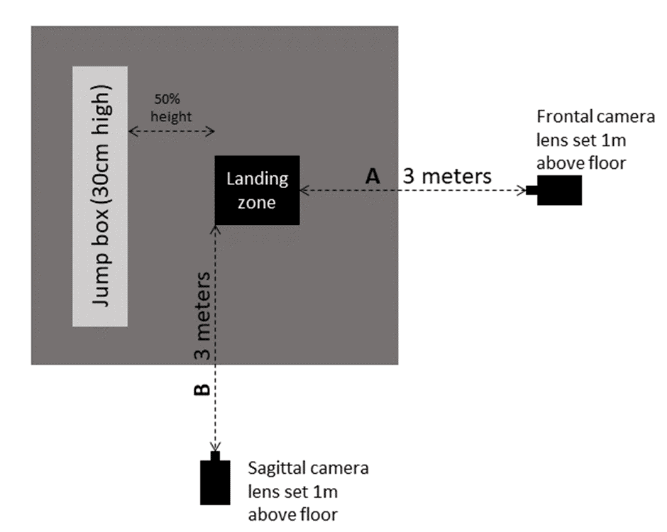

Figure 1 displays the test configuration for the LESS. This setup must be adhered to if accurate and reliable data is desired.

Test Procedure

The subject stands on a 30cm-high box half the body height away from the landing zone marked by a line on the ground. The subject is then instructed to jump forward so both limbs leave the box simultaneously aiming to land just past the line, and then jump for maximal height immediately after landing.

Video 1 demonstrates how the LESS is conducted and analysed.

Subjects can practice until comfortable with the task. No comment or guidance is provided unless performance does not follow the instructions. Any comment or judgment from the tester could disrupt the athlete’s performance and bias the test results.

Three trials should be recorded by two off-the-rack video cameras that are installed; one recording the subject from the front (A), and the other recording from the side (B). Each camera should be placed 3m away from the landing zone (Figure 1). The captured movement can then be evaluated at a later time.

How do you score the Landing Error Scoring System?

Based on a 19-point continuous scale (see FREE performance sheet), the LESS assesses the positioning of the trunk and lower extremities at various stages throughout the Drop-Vertical Jump (DVJ) movement. Using the performance recording sheet, the 1-15 items are scored dichotomically by adding either 1 or 0 to the final scores. Only items 16 and 17 add values 0, 1 or 2 depending on joint displacement and overall impression, respectively.

Therefore, a maximal score of 19 can be reached for exceptionally poor performances, while scores < 5 are regarded as “good” assuming low risk for ACL injury (8).

Is the Landing Error Scoring System valid and reliable?

The LESS was correlated against the gold standard, that is three-dimensional motion analysis (16) and showed good to excellent inter-rater and intra-rater reliability can be obtained (18, 20). LESS scoring of six items has “excellent” (84-100 %) agreement with 3D motion analysis (15).

LESS scores may vary widely in young athletes and military populations upon which the LESS was developed (17, 20). Clear cut-off values for LESS scores dividing low-risk groups from groups with a higher risk of obtaining ACL injury are thus difficult to establish. Commonly used cut-off values range between 5-5.5 (8). This results in ‘labelling’ athletes as low-risk with LESS scores of between 0 and 5, while a high-risk group contains individuals with a LESS score of 5 or higher. More studies must be conducted in the active population before normative data can be established (7).

It is being questioned whether the DVJ (which is not often associated with ACL injury itself (9)) is optimally challenging the knee while at the same time offering a safe, controlled and reproducible screening environment. More work should be done to provide enough evidence that increased knee motion during the drop vertical jump landing task actually increases the risk for non-contact ACL injury (20). Generic bilateral landing tasks (such as the DVJ) have limited predictive ability. To detect high-risk landing postures, sport-specific movements that are associated with ACL injuries may be a more appropriate approach to determining efficacy (9).

Repetitive screening is a big part of the job of a sports exercise and medicine clinician. Periodic health evaluations can show underlying pathologies and/or injuries, assess rehabilitation status and establish return-to-sport benchmarks for athletes (6). The utilisation of high-quality research tools to build an evidence base in sports exercise should focus on specific sports and relevant sub-groups (such as gender) (13), as well as on the topic of return-to-sport.

Conclusion

Despite its limitations, the LESS remains the instrument of choice in testing biomechanical behaviour to identify individuals with potentially ‘risky’ movement patterns. It is never the goal to expose athletes to high-risk tasks during testing. Even if it would offer better predictability, it also increases analysis and time burdens with screening.

The LESS is a method requiring minimal time and equipment (total set-up time per individual is under fiver minutes), and, is, therefore, applicable for a wide community. All evaluated movement patterns in the LESS actually increase the risk of attaining ACL injury in 3D motion analysis.

While all these evaluations seem confusing or misleading, they can be distilled down to one simple piece of advice, as below.

Use the LESS if:

- You have limited time and money.

- Work with a sporting population that has an increased risk of obtaining ACL injuries, due to repetitive jumping-landing manoeuvres.

- Want a valid and reliable tool to assess landing mechanics.

Don’t use the LESS:

- To predict an ACL injury and trigger fear-avoidance in an athlete.

- Or, as a replacement for a thorough medical assessment.

- Bahr, Roald (2016): Why screening tests to predict injury do not work-and probably never will… A critical review. In British journal of sports medicine 50 (13), pp. 776–780. DOI: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096256. http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/early/2016/04/19/bjsports-2016-096256

- Bell, David Robert; Smith, Mason D.; Pennuto, Anthony P.; Stiffler, Mikel R.; Olson, Matthew E. (2014): Jump-landing mechanics after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A landing error scoring system study. In Journal of athletic training 49 (4), pp. 435–441. DOI: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24905666

- Boden, B. P.; Griffin, L. Y.; Garrett, W. E. (2000): Etiology and Prevention of Noncontact ACL Injury. In The Physician and sportsmedicine 28 (4), pp. 53–60. DOI: 10.3810/psm.2000.04.841. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20086634

- Boden, Barry P.; Torg, Joseph S.; Knowles, Sarah B.; Hewett, Timothy E. (2009): Video analysis of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Abnormalities in hip and ankle kinematics. In The American journal of sports medicine 37 (2), pp. 252–259. DOI: 10.1177/0363546508328107. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19182110

- Boling, Michelle C.; Padua, Darin A.; Marshall, Stephen W.; Guskiewicz, Kevin; Pyne, Scott; Beutler, Anthony (2009): A prospective investigation of biomechanical risk factors for patellofemoral pain syndrome: the Joint Undertaking to Monitor and Prevent ACL Injury (JUMP-ACL) cohort. In The American journal of sports medicine 37 (11), pp. 2108–2116. DOI: 10.1177/0363546509337934. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19182110

- Clarsen, Ben; Moseby Berge, Hilde (2016): Screening is dead. Long live screening! In Br J Sports Med 50 (13), p. 769. DOI: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096475. http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/50/13/769?etoc=&utm_source=TrendMD&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=BJSM_TrendMD-0#ref-4

- Everard, Eoin M.; Harrison, Andrew J.; Lyons, Mark (2017): Examining the Relationship Between the Functional Movement Screen and the Landing Error Scoring System in an Active, Male Collegiate Population. In Journal of strength and conditioning research 31 (5), pp. 1265–1272. DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001582. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27465626

- Fox, Aaron S.; Bonacci, Jason; McLean, Scott G.; Spittle, Michael; Saunders, Natalie (2016): A Systematic Evaluation of Field-Based Screening Methods for the Assessment of Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injury Risk. In Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) 46 (5), pp. 715–735. DOI: 10.1007/s40279-015-0443-3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27292768

- Fox, A. S.; Bonacci, J.; McLean, S. G.; Saunders, N. (2017): Efficacy of ACL injury risk screening methods in identifying high-risk landing patterns during a sport-specific task. In Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 27 (5), pp. 525–534. DOI: 10.1111/sms.12715. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26626070

- Goerger, Benjamin M.; Marshall, Stephen W.; Beutler, Anthony I.; Blackburn, J. Troy; Wilckens, John H.; Padua, Darin A. (2015): Anterior cruciate ligament injury alters preinjury lower extremity biomechanics in the injured and uninjured leg: the JUMP-ACL study. In British journal of sports medicine 49 (3), pp. 188–195. DOI: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092982. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24563391

- Hewett, Timothy E.; Myer, Gregory D.; Ford, Kevin R.; Heidt, Robert S.; Colosimo, Angelo J.; McLean, Scott G. et al. (2016): Biomechanical Measures of Neuromuscular Control and Valgus Loading of the Knee Predict Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Risk in Female Athletes. In Am J Sports Med 33 (4), pp. 492–501. DOI: 10.1177/0363546504269591. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0363546504269591

- James, Joan; Ambegaonkar, Jatin P.; Caswell, Shane V.; Onate, James; Cortes, Nelson (2016): Analyses of Landing Mechanics in Division I Athletes Using the Landing Error Scoring System. In Sports health 8 (2), pp. 182–186. DOI: 10.1177/1941738115624891. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26721287

- La Motte, Sarah J. de; Gribbin, Timothy C.; Lisman, Peter; Beutler, Anthony I.; Deuster, Patricia (2016): The Interrelationship of Common Clinical Movement Screens. Establishing Population-Specific Norms in a Large Cohort of Military Applicants. In Journal of athletic training 51 (11), pp. 897–904. DOI: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.9.11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27831746

- Markbreiter, Jessica G.; Sagon, Bronson K.; Valovich McLeod, Tamara C.; Welch, Cailee E. (2015): Reliability of clinician scoring of the landing error scoring system to assess jump-landing movement patterns. In Journal of sport rehabilitation 24 (2), pp. 214–218. DOI: 10.1123/jsr.2013-0135. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27831746

- Onate, James; Cortes, Nelson; Welch, Cailee; van Lunen, Bonnie L. (2010): Expert versus novice interrater reliability and criterion validity of the landing error scoring system. In Journal of sport rehabilitation 19 (1), pp. 41–56. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20231744

- Padua, Darin A.; Boling, Michelle C.; Distefano, Lindsay J.; Onate, James A.; Beutler, Anthony I.; Marshall, Stephen W. (2011): Reliability of the landing error scoring system-real time, a clinical assessment tool of jump-landing biomechanics. In Journal of sport rehabilitation 20 (2), pp. 145–156. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21576707

- Padua, Darin A.; Marshall, Stephen W.; Boling, Michelle C.; Thigpen, Charles A.; Garrett, William E.; Beutler, Anthony I. (2009): The Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) Is a valid and reliable clinical assessment tool of jump-landing biomechanics: The JUMP-ACL study. In The American journal of sports medicine 37 (10), pp. 1996–2002. DOI: 10.1177/0363546509343200. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25811846

- Padua, Darin A.; Distefano, Lindsay J.; Beutler, Anthony I.; La Motte, Sarah J. de; DiStefano, Michael J.; Marshall, Steven W. (2015): The Landing Error Scoring System as a Screening Tool for an Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury-Prevention Program in Elite-Youth Soccer Athletes. In Journal of athletic training 50 (6), pp. 589–595. DOI: 10.4085/1062-6050-50.1.10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19726623

- Read, Paul J.; Oliver, Jon L.; Ste Croix, Mark B. A. de; Myer, Gregory D.; Lloyd, Rhodri S. (2017): A Review Of Field-Based Assessments Of Neuromuscular Control And Their Utility In Male Youth Soccer Players. In Journal of strength and conditioning research. DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000002069. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28658071

- Smith, Helen C.; Johnson, Robert J.; Shultz, Sandra J.; Tourville, Timothy; Holterman, Leigh Ann; Slauterbeck, James et al. (2012): A prospective evaluation of the Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) as a screening tool for anterior cruciate ligament injury risk. In The American journal of sports medicine 40 (3), pp. 521–526. DOI: 10.1177/0363546511429776. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22116669