Contents of Article

- Summary

- Introduction

- What is maturation?

- How does maturation affect sports performance?

- How do you measure maturation?

- What future research is needed on maturation?

- Conclusion

- About the Author

Summary

Maturation is simply the process of children growing and obtaining adult stature. All humans experience maturation differently, but we notice the greatest change after puberty. Females tend to mature sooner than boys, but post-pubertal boys will experience greater increases in strength and power due to testosterone and other androgen hormones.

An appropriate strength and conditioning programme will increase the motor skills, coordination, strength and power in children and adolescents. Adolescents may be prone to overuse injuries during periods of rapid growth in height and mass. Maturation should be measured in youth athletes to properly monitor their growth and well-being as athletes.

Research into the area of maturation (1, 2) and its impact on the performance of young athletes has recently gained popularity in the field of sport and exercise science. By now, many sport coaches understand that resistance training can have a positive effect on the health and performance of children and adolescents.

However, some may not know what is an appropriate strength and conditioning programme or how it can affect growth and enjoyment in sports. Having a basic understanding of the concepts related to maturation (e.g. motor development and injury risk) can assist coaches with managing their young athletes and preparing them for future success in sport.

What is maturation?

Maturation is quite simply the process of becoming mature (3). To understand maturation properly, we must realise that each child differs in the timing and tempo of this process. Timing refers to ‘when’ maturation begins, while tempo refers to the ‘rate’ at which it progresses.

We typically discuss maturation as the process from early childhood, to adolescence and then to full adult stature. Childhood is generally regarded as the time until which one reaches adolescence. The start of adolescence begins with the onset of puberty where hormonal and physical changes begin to occur (3). Initially, rapid changes begin to occur with increases in height, weight, stature and the development of secondary sex characteristics (3).

Up until puberty, there are few performance differences between genders (4). The adolescent stage usually begins sooner in girls (8-19 years) than in boys (10-22 years) (3), but up until puberty, there are few performance differences between genders (4). However, significant changes begin to emerge between genders after puberty due to circulating androgens (testosterone) (3). Testosterone causes boys to develop larger arm girth (5) and larger shoulder breadth in comparison to girls, while increases in hip breadth are alike (3). Similarly, during this rapid growth spurt, boys will have greater fat-free mass than girls and a smaller increase of body fat.

How does maturation affect sports performance?

Maturation plays a significant role in motor skill development, strength, power, and even impacts injury risk in young athletes. Understanding maturation and how it impacts youth performance is of great benefit to coaches and parents.

Research indicates that childhood is an ideal and opportunistic time in which to maximise motor skill proficiency (6-8). This is due to the natural and accelerative rate at which the brain (6) and central nervous system (9) mature in the child. Therefore, this vital time frame should be utilised by introducing children to a broad array of foundational movements, as well as exposing them to a variety of stimuli (10). If such foundational movements are developed before adolescence, it is believed that the athlete will be better equipped when faced with more complex motor skills during a later developmental stage.

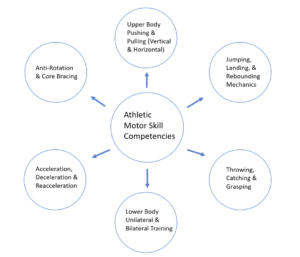

As athletes reach adolescence and adulthood, they are less sensitive to developing new motor pathways (11), which therefore makes it more difficult to teach certain movement skills. As a result, youth athletic development programmes should be thoughtfully designed and carefully delivered in order to ensure the programme has maximal effect. Moreover, young athletes should be exposed to a range of different stimuli, however, this must not be delivered in a random or poorly thought-out format. Instead, the goal and focus of training sessions should be to develop gross athletic motor skill competencies (Figure 1) through a challenging and playful environment.

After puberty, strength increases develop differently between genders. However, it is important to understand that strength still remains trainable as children mature. As maximal strength seems to increase steadily for boys as they approach full adult maturity, girls tend to experience a plateau (3). It has been reported the gap between strength and power widens between genders in the years after puberty (4).

Despite this separation, both genders can expect significant increases in muscular strength and power following an appropriate short-term resistance training programme (12, 13). Having said that, this increase in strength is highly individualised as certain children respond more favourably than others (14). Resistance training can also bring about improvements in bone health (15), body composition (16), and self-esteem (17). Strength training produces many benefits for maturing children and may also provide implications for reducing injury.

Until recently, common thought outside of the sport and exercise community was that resistance training in children and adolescents was a major safety risk and detrimental to natural growth. However, it has been shown that children are much more likely to get injured during competition than they would be performing an appropriately delivered strength and conditioning programme (18). While exposure to strength and power is beneficial to the muscles, bones and soft tissue, they may still be at risk to overuse injuries.

Overuse injuries are a major problem for young athletes who are experiencing periods of rapid growth (19), and who are also being exposed to tremendous training loads. This can be brought about unintentionally by both sport coaches and practitioners who fail to recognise these important red flags (i.e. rapid growth and high training loads). Therefore, coaches who work with young athletes who are close to peak height velocity and peak weight velocity should consider their athletes’ growth rates, training loads, and levels of fatigue on a regular and ongoing basis.

How do you measure maturation?

While the timing and tempo of maturation differs for everyone, there are various methods to measure and accurately predict the growth of the human body. The best way to measure maturity status is through a radiograph of the athlete’s skeleton. However, this method is limited in its availability to coaches and large groups of athletes.

The next best method is by using the Mirwald equation (20), which is based on anthropometric ratio measures of the body. Specifically, the ratio of sitting height to leg length (20).

Genetics also play a huge role in estimating stature of a child. By using the height of both parents, you can calculate the mid-parent stature (21) of both boys and girls. If you wish to use this method, then click here to download your free bio-banding calculator so you can predict the adult height of your athletes and then group them based on their maturity.

Similarly, Sherar et al. (2005) (22) generated an equation to predict adult stature for adolescent boys and girls. A more pragmatic and traditional approach could be to regularly monitor the height and body mass of your young athletes. Three-month intervals should be a suitable interval time period at which you can monitor and detect rapid growth.

What future research is needed on maturation?

Although a lot is already understood about maturation, there is still far more to research and discover about this natural process. Such things include:

- How does maturation affect our ability to absorb and produce force in tests such as the drop jump?

- Does a strength and conditioning programme elicit hormonal responses in children that affect the onset of puberty?

- Does maturation timing and tempo affect or reflect sporting success as adults?

Conclusion

Maturation is simply the process of children growing and obtaining adult stature. This process is highly individualised, although there are distinct differences between genders after puberty. Children and adolescents should be exposed to a strength and conditioning programme that introduces them to a plethora of movements and motor skills.

There are several methods by which we can predict the stature of children as well as monitor them as they mature. Adolescents are at high risk for overuse injuries during times of extreme growth and high training loads; therefore, coaches should be extremely vigilant during these periods. Properly managing a child’s well-being during periods of maturation can support their health, assist their sporting success, and even promote their overall enjoyment of sport.

- Lloyd, R. S., Oliver, J. L., Meyers, R. W., Moody, J. A. and Stone, M. H. (2012). Long Term Athletic Development and Its Application to Youth Weightlifting. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research,34:55-66. http://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/Abstract/2012/08000/Long_Term_Athletic_Development_and_Its_Application.10.aspx?trendmd-shared=0

- Lloyd, R. S., Oliver, J. L., Hughes, M. G. and Williams, C. A. (2011) The Influence of Chronological Age on Periods of Accelerated Adaptation of Stretch-Shortening Cycle Performance in Pre- and Post-Pubescent Boys. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 25: 1889-1897. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21499135

- Lloyd, R. S., and Oliver, J. L. Strength and Conditioning for Young Athletes: Science and Application. Routledge, 2014. https://www.routledge.com/Strength-and-Conditioning-for-Young-Athletes-Science-and-Application/Lloyd-Oliver/p/book/9780815361831?srsltid=AfmBOooE09TRIJWhaL0yW9OwgVM4aeF842u6JemBmAX0zqmlroQjpuFM

- Catley, M. J. and Tomkinson, G. R. (2012). Normative Health-Related Fitness Values for Children: Analysis of 85347 Test Results on 9-17-Year-Old Australians Since 1985. British Journal of Sports Medicine, e-pub, March. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22021354

- Malina, R. M., Bouchard, C. and Bar-Or, O. (2004) Growth, Maturation, and Physical Activity. 2nd Edition, Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. http://www.humankinetics.com/products/all-products/growth-maturationnd-physical-activity-2nd-edition

- Casey, B. J., Tottenham, N., Liston, C. and Durston, S. (2005). Imaging the Developing Brain: What Have We Learned About Cognitive Development. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9: 104-110. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15737818

- Faigenbaum, A. D., Farrell, A., Fabiano, M., Radler, T., Naclerio, F., Ratamess, N. A., Kang, J. and Myer, G. D. (2011). Effects of Integrative Neuromuscular Training on Fitness Performance in Children .Pediatric Exercise Science, 23: 573-584. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22109781

- Myer, G. D., Faigenbaum, A. D., Ford, K. R., Best, T. M., Bergeron, M. F. and Hewett, T. E. (2011). When to Initiate Integrative Neuromuscular Training to Reduce Sports-Related Injuries and Enhance Health in Youth? Current Sports Medicine Reports, 10: 157-166. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21623307

- Viru, A., Loko, J., Harro, M., Volver, A., Laaneots, L. and Viru, M. (1999). Critical Periods in the Development of Performance Capacity During Childhood and Adolescence. European Journal of Physical Education, 4: 75-119. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1740898990040106

- Lloyd, R. S., and Oliver, J. L. (2012). The Youth Physical Development Model: A New Approach to Long Term Athletic Development. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 34: 61-72. http://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/Abstract/2012/06000/The_Youth_Physical_Development_Model___A_New.8.aspx

- Sowell, E. R., Thompson, P. M. and Toga, A. W. (2001). Mapping Continued Brain Growth and Gray Matter Density Reduction in Dorsal Frontal Cortex: Inverse Relationship During Post Adolescent Brain Maturation. The Journal of Neuroscience, 21: 8819-8829. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11698594

- Falk, B. and Tenenbaum, G. (1996). The Effectiveness of Resistance Training in Children: A Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine, 22:176-186. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8883214

- Faigenbaum, A. D., Kraemer, W. J., Blimkie, C. J. R., Jeffreys, I., Micheli, L. J., Nika, M. and Rowland, T. W. (2009). Youth Resistance Training: Updated Position Statement Paper from the National Strength and Conditioning Association. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 23: S60-S79. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19620931

- Faigenbaum, A. D. (2011). Strength Training for Children and Adolescents. In: M. Cardinale, R. Newton and K. Nosaka (eds) Strength and Conditioning: Biological Principles and Practical Applications, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. http://eu.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-EHEP002346.html

- Vicente-Rodriguez, G. (2006). How Does Exercise Affect Bone Development During Growth? Sports Medicine, 36: 561-569. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16796394

- Watts, K., Jones, T. W., Davis, E. A. and Green, D. (2005). Exercise Training in Obese Children and Adolescents. Sports Medicine, 35: 375-392. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15896088

- Tucker, L. (1987). Effect of Weight Training on Body Attitudes: Who Benefits Most? Journal of Sports Medicine, 27: 70-78. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3599976

- Rugby Football Foundation, RFU Injured Players Foundation, RFU, University of Bath. Report on injury risk in English youth rugby union. Retrieved from https://www.englandrugby.com/run/player-welfare/headcase

- Hutchinson, M. R. and Nasser, R. (2000). Common Sports Injuries in Children and Adolescents. Medscape Orthopaedics & Sports Medicine eJournal. Online. Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/408524_4 (accessed 30 October 2017).

- Mirwald, R. L., Baxter-Jones, A. D. G., Bailey, D. A. and Beunen G. P. (2002). An Assessment of Maturity from Anthropometric Measures. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 34: 689-694. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11932580

- Tanner, J. M., Goldstein, H. and Whitehouse, R. H. (1970). Standards for Children’s Height at Ages 2-9 Years Allowing for Height of Parents. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 45: 755-762. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1647404/

- Sherar, L. B., Mirwald, R. L., Baxter-Jones, A. D. and Thomis, M. (2005). Prediction of Adult Height Using Maturity-Based Cumulative Height Velocity Curves. Journal of Pediatrics, 147: 508-514. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16227038