Contents of Article

- Summary

- What is the Y Balance Test?

- Why use the Y Balance Test?

- How do you conduct the Y Balance Test?

- How to calculate the Y Balance Test score?

- Is the Y Balance Test valid and reliable?

- References

- About the Author

Summary

The Y Balance Test™ was developed to refine the lengthy process of conducting the Star Excursion Balance Test. As such, most of the supportive research for the Y Balance Test™ is based on the investigations conducted on the Star Excursion Balance Test. Nevertheless, the Y Balance Test™ has not only proven itself to have a high level of test–retest reliability but also to be a sensitive indicator of injury risk among athletes.

What is the Y Balance Test?

The Y Balance Test™ (YBT) is a simple, yet reliable, test used to measure dynamic balance and a person’s risk of injury (1). The test can be performed on both the upper and lower quarters of the body. It was developed to standardise the modified Star Excursion Balance Test (mSEBT), improve its practicality, and make it commercially available (1). Since then, the YBT has gone on to become an extremely popular test due to its simplicity and reliability.

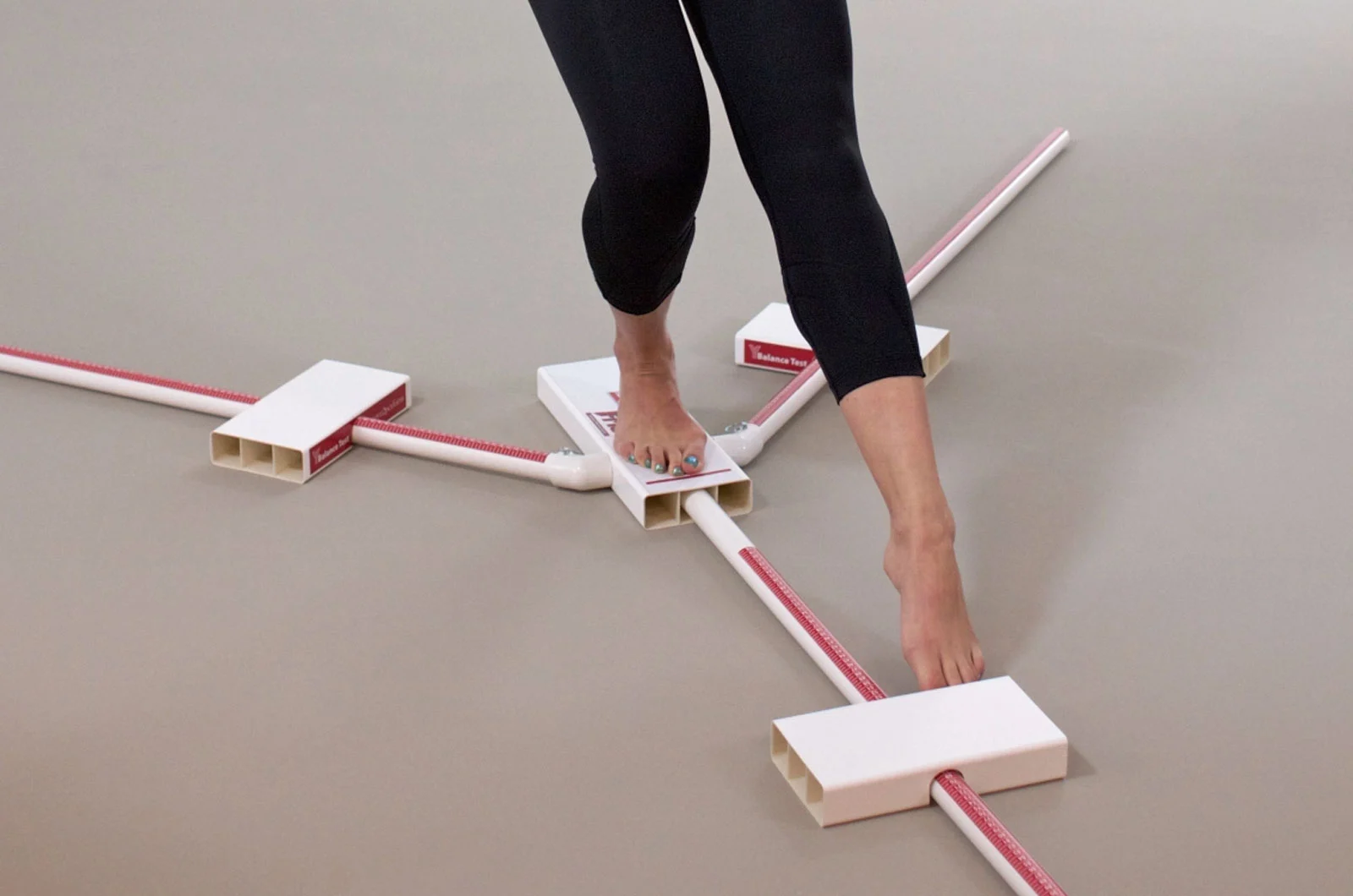

The YBT requires the athlete to balance on one leg whilst simultaneously reaching as far as possible with the other leg in three separate directions: anterior, posterolateral, and posteromedial. Therefore, this test measures the athlete’s strength, stability and balance in various directions. The YBT composite score is calculated by summing the three reach directions and normalising the results to the lower limb length, whereas asymmetry is the difference between right and left limb reach (1) – this is explained in greater detail in the scoring system section.

Whilst previous injury or surgery appears to have no impact on test performance in collegiate athletes (1), the test has been shown to have strong relationships with knee flexor and hip abductor strength (2). Though little research has been conducted on the YBT and athletic injury risk, most of the assumptions regarding injury risk are extracted from research on the SEBT due to its large similarity to the YBT. For example, an anterior reach asymmetry of greater than 4cm during the SEBT has been suggested to predict which individuals are at risk of lower limb injury (3).

However, other researchers have found that only female athletes with a composite score of less than 94 % of limb length were at greater risk of injury (3). More recent research in collegiate American football players has shown athletes with a composite score of less than 90 % are 3.5 times more likely to sustain an injury (4). Additional research has also highlighted that poor performance on the SEBT is related to chronic ankle instability (5). All of this information suggests that each sport and population (e.g. gender) appear to have their own injury risk cut-off point (3, 4).

Why use the Y Balance Test?

Balance, otherwise known as ‘postural control’, can be defined statically as the ability to maintain a base of support with minimal movement, and dynamically as the ability to perform a task while maintaining a stable position (6, 7). In a chaotic sporting environment, the ability to maintain a stable position is vital not only for the successful application of the skill but to also reduce the likelihood of injury (8, 3, 4). As a result, it may be of great interest to test and monitor an athlete’s dynamic stability.

How do you conduct the Y Balance Test?

It is important to understand that whenever fitness testing is performed, it must be done so in a consistent environment (e.g. facility) so it is protected from varying weather types, and with a dependable surface that is not affected by wet or slippery conditions. If the environment is not consistent, the reliability of repeated tests at later dates can be substantially hindered and result in worthless data.

Required Equipment

Before the start of the test, it is important to ensure you have the following items:

- Reliable and consistent testing facility (minimum 2×2 metres).

- Test administrator(s)

- Y Balance test kit, or sticky tape and a measuring tape.

- Performance recording sheet

Test Configuration

Video 1 displays the test configuration and procedure for the YBT. This setup and protocol must be adhered to if accurate and reliable data is desired.

Planning an Effective Warm-Up

To plan an effective warm-up, the strength and conditioning coach must first understand the mental, physiological, and biomechanical demands of the training session or sport before they attempt to prepare the athlete for these precise demands. In most circumstances, these demands are identified during the need analysis.

For example, if a strength and conditioning coach is planning a warm-up for some 1 repetition maximum (1RM) testing, then they might want to consider what the mental, physiological, and biomechanical demands of that session are. For mental preparation, the coach may encourage the athletes to arrive well-rested and to bring personal self-motivating music to listen to whilst testing – as this has been repeatedly shown to improve performance (24). To prepare them physiologically, the coach may adopt a warm-up routine with similar physiological demands to 1RM testing, such as high-force/strength, and long-rest exercises. In terms of biomechanical preparation, stretches, dynamic movements and exercises similar to those being performed during testing would be appropriate (e.g. back squatting).

Alternatively, if a strength and conditioning coach is designing a pitch-based warm-up for a ‘short and sharp’ technical session for football (soccer), then the warm-up should be designed specifically for that session and therefore may look very different to the previous 1RM testing example. The mental preparation may likely be very different, as the players’ mental readiness may be stimulated by competing against other players – as an example. Physiologically, if the technical session demands high work volumes with short recovery periods, and thus a high cardiovascular demand, then the warm-up should aim to produce similar or even replicate the intensities the athletes will be exposed to. From a biomechanical standpoint, the adopted movements should have biomechanical similarities to the movements which will be prevalent during the technical session. This may include things such as lunges, directional changes, jumping, and twisting movements.

Remember, the warm-up can be structured effectively and strategically using the RAMP protocol and the content/ exercises should replicate those of the session the athletes are preparing for.

Warm Up

Participants should thoroughly warm up prior to the commencement of the test. Warm-ups should correspond to the biomechanical and physiological nature of the test. In addition, sufficient recovery (e.g. 3-5 minutes) should be administered following the warm-up and prior to commencement of the test.

Conducting the test

IMPORTANT: This testing procedure is explained when using the YBT kit.

- The athlete should be wearing lightweight clothing and remove their footwear. After doing so, they are then required to stand on the centre platform, behind the red line, and await further instruction.

- The test should be performed in the following order:

- Right Anterior

- Left Anterior

- Right Posteromedial

- Left Posteromedial

- Right Posterolateral

- Left Posterolateral

- With their hands firmly placed on their hips, the athlete should then be instructed to slide the first box forward as far as possible with their right foot and return back to the starting upright position.

- Reach distances should be recorded to the nearest 0.5cm (9).

- They should then repeat this with the same foot for a total of three successful reaches. After they have completed three successful reaches with their right foot, they are then permitted to repeat this process with their left foot.

- Once the athlete has performed three successful reaches with each foot, they can then progress onto the next test direction (i.e. posteromedial).

- The test administrator should record the reach distance of each attempt in order to calculate the athlete’s YBT composite score.

NOTE: Failed attempts include the following:

- The athlete cannot touch their foot down on the floor before returning back to the starting position. Any loss of balance will result in a failed attempt. However, once they have returned to the starting position, they are permitted to place their foot down behind the centre/balance foot box.

- The athlete cannot place their foot on top of the reach indicator in order to gain support during the reach – they must push the reach indicator using the red target area.

- The athlete must keep their foot in contact with the target indicator until the reach is finished. They cannot flick, or kick, the reach indicator in order to achieve a better performance.

How to calculate the Y Balance Test score?

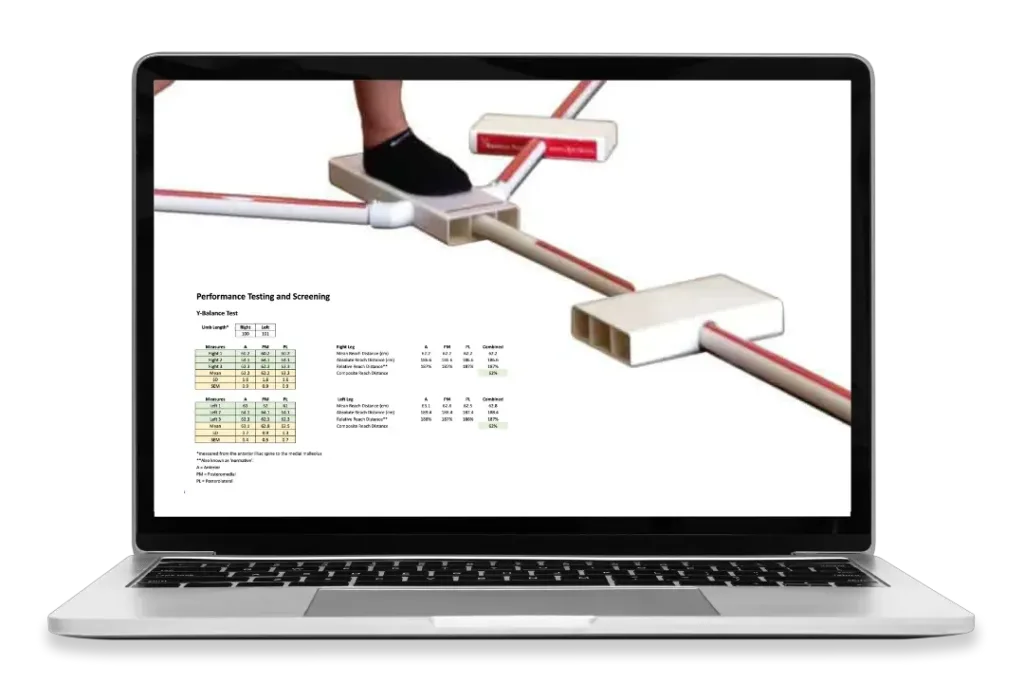

With the test complete and all performances recorded, the test administrator can then calculate the athlete’s YBT performance scores using any of, or all of, the following three equations (9):

- Absolute reach distance (cm) = (Reach 1 + Reach 2 + Reach 3) / 3

- Relative (normalised) reach distance (%) = Absolute reach distance / limb length * 100

- Composite reach distance (%) = Sum of the 3 reach directions / 3 times the limb length * 100

Is the Y Balance Test valid and reliable?

The YBT has proven to have very good levels of interrater test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.80 – 0.85) when measured by entry-level doctorate physical therapy students (9). In support of this, another study found that Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) for intrarater reliability ranged from 0.85 to 0.91 and for interrater reliability ranged from 0.99 to 1.00. Composite reach score reliability was 0.91 for intrarater and 0.99 for interrater reliability (10).

- Chimera NJ, Smith CA, Warren M. Injury History, Sex, and Performance on the Functional Movement Screen and Y Balance Test. Journal of Athletic Training 2015;50(5):475–485. [PubMed]

- Lee DK, Kang MH, Lee TS, Oh JS. Relationships among the Y balance test, Berg Balance Scale, and lower limb strength in middle-aged and older females. Braz J Phys Ther. 2015 May-June; 19(3):227-234. [PubMed]

- Plisky PJ, Rauh MJ, Kaminski TW, Underwood FB. Star Excursion Balance Test as a predictor of lower extremity injury in high school basketball players. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36(12):911–919. [PubMed]

- Butler RJ, Lehr ME, Fink ML, Kiesel KB, Plisky PJ. Dynamic balance performance and noncontact lower extremity injury in college football players: an initial study. Sports Health. 2013;5(5): 417–422. [PubMed]

- Hubbard T. J., Kramer L. C., Denegar C. R., Hertel J. Contributing factors to chronic ankle instability. Foot Ankle Int. Mar 2007;28(3):343- 354. [PubMed]

- Bressel E, Yonker JC, Kras J, Heath EM. Comparison of Static and Dynamic Balance in Female Collegiate Soccer, Basketball, and Gymnastics Athletes. Journal of Athletic Training 2007;42(1):42–46. [PubMed]

- Winter DA, Patla AE, Frank JS. Assessment of balance control in humans. Med Prog Technol. 1990;16:31–51. [PubMed]

- Zazulak B, Cholewicki J, and Reeves NP. Neuromuscular control of trunk stability: Clinical implications for sports injury prevention. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 16: 497–505, 2008. [PubMed]

- Shaffer SW, Teyhen DS, Lorenson CL, Warren RL, Koreerat CM, Straseske CA, Childs JD. Y-Balance Test: a reliability study involving multiple raters. Mil Med. 2013;178(11):1264-70. [PubMed]

- Plisky PJ, Gorman PP, Butler RJ, Kiesel KB, Underwood FB, Elkins B. The reliability of an instrumented device for measuring components of the star excursion balance test. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2009 May;4(2):92-9. [PubMed]