Youth athletes: How can teachers, coaches and students best juggle their intense schedules?

Youth development is highly complex and involves multiple key stakeholders. But how can coaches, teachers and youth athletes themselves best work together?

Youth athlete development: It’s all about teamwork

Despite the vast movements in sports science in recent years, the simplest of things, such as effective communication, can often go amiss. Take humans for example. Humans are innately social beings, who value the opinions and interactions of their peers to feel worth and self-efficacy.

When combined, opinions can be a powerful vehicle for personal development and growth. Such processes allow sports scientists to give their athletes the most informed and educated training methodology to drive performance.

Good inclusive communicators are skilled in their ability to concisely lay out a plan whilst causing little offence or alienation to others. Mastering this skill is increasingly important when multiple sports science agencies are involved in working with individuals or groups.

Take my line of work for example. I am the Head of Athletic Development at a Secondary School (11-19yrs) in England, where I deliver strength and conditioning lessons over a seven-year LTAD programme. Out of the 167 students I work with daily, at least 75% are coached by someone other than myself. Moreover, at least 37% receive strength and conditioning (S&C) support from at least two coaches. Over time, I have had to surrender something I hold dear when working with athletes: control.

At first, the very thought of competing with another coach’s programme is an innate challenge. My job, after all, places me in a position of responsibility to maintain and develop athletic qualities in a safe and ethical manner under one organisation. The term ‘sharing is caring’ doesn’t apply here acutely, as I’ve been involved in my fair share of unsuccessful collaborative work with external S&C coaches. But then I get a little bit excited – it can be a great opportunity to network, collaborate and spearhead a new journey for the athlete(s) at hand. Once I get into this head space, losing control doesn’t seem as intimidating.

When talking about control here, this isn’t inherently what everyone would instantly think. “You want all of the success for yourself” or “you are reluctant to share”. No. That’s not it. It’s more of a desire to avoid conflicting priorities. A bit of ego mixed with fear. “I know this athlete and I know what’s best for them” coupled with a work-load conundrum. Who can blame me? The majority of research is in and of itself monodisciplinary in nature.

Benefits and downsides of a monodisciplinary approach

I read. I read a lot, in fact. While many of you are on your Kindles, reading illustrious stories and drifting into a sleepy state, I am sifting through PDFs and making notes. This probably isn’t healthy and I’m not an advocate of this approach; however, this has made me more aware of how poor research can be from a holistic sense.

Let’s say I read a hypothetical journal article titled ‘The influence of one-repetition max strength on speed in youth football players’ – sounds pretty good actually. As an S&C coach, I read this to understand the programming methodology, sets, reps, distances … the good stuff. I apply my own biases and then think about how/if I should incorporate this into my system.

The reason I can do this is because I do not have to consult with other coaches, scientists or therapists – this is what I mean by a monodisciplinary approach. I work with my athlete and no one else. My relationship is strictly one-to-one and selfishly, I don’t have to worry about the opinions of others or how their programmes may interact with mine.

The benefits of this approach are there is little room for intragroup conflict, programming becomes more linear and thus predictable, and I have a strong handle on the programming direction for that individual. This happens in many schools across the UK and isn’t necessarily a bad thing. We do after all want children to receive S&C support for all of the known benefits. But what about if two coaches come into the equation, which often happens when young athletes play at clubs and organisations outside of school and receive coaching advice externally?

Now we have two coaches – I have my programme, they have theirs. This is an example of a multidisciplinary approach, where although collaboration is possible, both can still work independently of one another. The issue with this, although seemingly obvious, is many youths miss out on their ability to develop optimally due to conflicting programming: I set a heavy rep scheme, the other coach set a heavy rep scheme – and who suffers? The athlete, who is bombarded by a constant fluctuation of load and volume because two adults can’t send an email, pick up the phone, or better yet – meet in person.

Collaboration is key with youth athlete training

Another example I hear you say? Sure. This athlete also suffers with pre-match anxiety and consults with a sport psychologist. Meanwhile, the club’s nutritionist prescribes caffeine as an ergogenic aid to improve performance and heighten readiness, despite its anxiogenic properties. Here, two agencies are working with the individual but are having little to no contact, so while the athlete is benefitting from psychological support, they are still feeling tight-chested and nervous before competing. In the absence of communication here, both disciplines think they are doing right by the athlete.

Where there is little-to-no communication, those who are supporting an athlete become islands. Sure, they may make tiny gains in developing athleticism, but a collaborative approach has the benefit of widening the magnifying glass, allowing coaches, teachers and sports scientists to observe how different disciplines work together for the benefit of the athlete (See figure below).

Figure 1: Mono, multi, and inter disciplinary support and its ability to make meaningful change.

Figure 1: Mono, multi, and inter disciplinary support and its ability to make meaningful change.

Unlike a multidisciplinary approach, interdisciplinary models attempt to align theoretical principles with practical delivery solutions in a coordinated and integrated manner. Collaborative problem-solving can support sports scientists in appreciating the diverse ways of thinking, approaching, and developing new systems or ways of practice. Although this may be considered the ‘gold-standard’ of collaboration, there are some considerations that need to be made. For example, interdisciplinary approaches heighten the risk of:

- More experienced members are likely to dominate conversations and over emphasise the importance of their input.

- Collaboration heightens the likelihood of the ‘risky shift’ phenomenon, where practitioners take poorly measured steps to gain social status.

- Increases the likelihood of the groupthink phenomenon, where members agree to reduce conflict.

As you can now hopefully see, collaboration doesn’t always lead to improved productivity, so developing strong relationships that are built on trust, transparency and effective communication is key.

So how can coaches use this information practically? Well…

Youth athlete training – it all starts with a conversation

Getting to know your athletes is an essential part of being a great coach, teacher and sports scientist. Once you engage in conversations and develop rapport, you’ll be amazed at how much they will tell you. For example, you are midway through a set and all of a sudden, your athlete opens up to you out of the blue and says “we do something similar to this at our academy”. This can stop you in your tracks a little bit, but then you’re instantly filled with a little bit of excitement. Let’s go off topic for a paragraph:

Coaching 101 – Moments where an athlete confides that your work is similar to what they are doing at their academy or club marks a really great way to get buy-in. Once they tell you this, show as much interest as possible. Find out what they do, how they do it, and how they are coached through the movement. Reserve any judgement. Just let them speak to you and if it doesn’t harm your programme, even look to incorporate it. Now let’s get back on track…

Once you get the athlete’s permission, the first stage is to contact their coach. In my opinion, a face-to-face meeting is the best method for this, but a telephone/computer call is the second-best option. In the first encounter, the most important objective in my opinion is to be human. Topical subjects, discussing your relationship with the athlete and being empathetic to their role is important. If you go in with a righteous or entitled attitude, you may meet a coach who stands off and has a reserved opinion and/or is reluctant to help.

Promoting a positive environment in this first encounter is essential. Being accepting of their ideas and showing a strong willingness to share is a great way to remove any barriers that may exist. To elaborate on this further, encouraging the other party to describe their role with this athlete, being appreciative of their efforts and offering helpful feedback are all great ways to show shared purpose. People who feel appreciated are often inclined to speak again.

Get to know yourself – and the people around you

An issue I’ve had when meeting coaches before is having some form of bias. My biggest advice here is to drop your ego and go in with an open policy to change. Some of the collaborative partners with the biggest reputation have offered the lowest returns, whilst the ‘amateur’ coach has given me a thousand doses of wisdom.

However hard it may sound, don’t make inferences from the information you receive immediately. Coaches, parents and other sports scientists tend to jump to conclusions in the absence of context. I’ve done this many times. Conclusions drawn from pure speculation are very seldom accurate, especially when there is emotion involved. If you are unsure what an individual means, ask them to clarify and give them the opportunity to provide some more context. Usually, you can clear up any misconceptions here.

However, an important point to remember on your first encounter is not to be a pushover, especially if you are the first person to make contact. I’ve had plenty of encounters where coaches make assumptions about my programme. Striking a balance can be hard, but it’s really important that you do not undersell your priorities as well. Good relationships are reciprocal, and you can gain value by digging in your heels from time to time and showing that your intentions do matter. Avoid being aggressive/condescending, but just be firm and bring it back to the fact that you are there to help the athlete first and foremost. Listening more than you talk, nodding and offering your insight on the individual helps to reinforce your common purpose (the athlete).

In my experience, you can’t do everything in one call, so you better be prepared for the long-haul. A follow up email of “really enjoyed our conversation the other day, would like to do this again soon” shows a great sign of intent – you want to do this again, frequently. Simultaneously, you may want to contact the parent to say you’ve had a great chat with their club and are looking to align your programmes to help their son/daughter. The benefits of this are twofold. Firstly, the parents know you are offering a credible service to their child, and secondly, you establish a clear investment in their child’s long-term athletic development – it’s a win-win.

On the second meet/call, it’s good to bring some practical programming to converse about. As mentioned earlier, never play down the importance of your objectives. Power should be distributed evenly here, as you can help them as much as they can help you. By the end of this meeting, clear expectations should be set so that individuals know exactly who is doing what so that training priorities do not overlap. This is a great way to avoid injuries and overreaching.

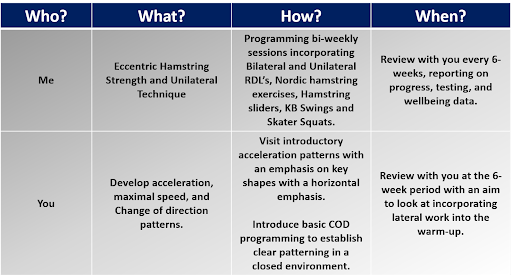

The ‘who, what, how and when’ method is one of my favourites to introduce to a coach, as this is a clear contract outlining accountability (See Table 1):

Table 1: The who, what, how and when method for developing interdisciplinary collaboration.

Table 1: The who, what, how and when method for developing interdisciplinary collaboration.

Once this is established, you each have a fantastic blueprint for your programming. To establish trust in this method, it’s really important you don’t tread on their toes. Stay in your lane and do your bit really well. This simple method is accountability criteria. You do your bit and I’ll do mine, nothing more, nothing less.

You’ve taken some big strides … now what?

Now your relationship has been established, you need to maintain it. My top tips for maintaining your relationships is to continue to be open and honest about your progress. Here, you must have the confidence to talk openly about your project and any issues that you are facing along the way. Give yourself the same sympathy you would afford others who confide in you from an open and honest place. In turn, you will gain respect, trust and appreciation in your approach to youth development.

Regular messages help to maintain a relationship, so remember to make contact. My old-school method of a post-it note with a reminder to contact a coach/other member of the sports science team has since been replaced with a reminder app that tells me it’s time to contact ‘Joe Bloggs’. This is another great way to show the other party they are involved in your decision-making processes.

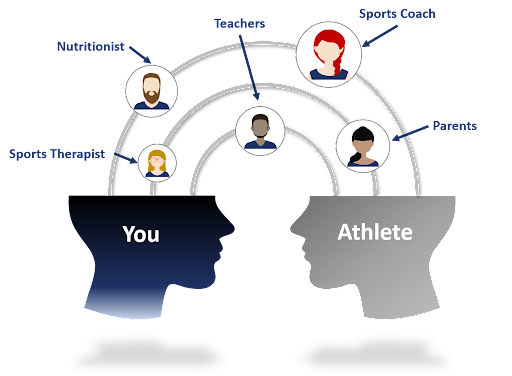

Now that you are in the ‘circle of trust’, look to expand this relationship to other members of the athlete’s support network. Over time, you can move towards providing interdisciplinary support which will lead to meaningful change (See Figure 2).

Figure 2

Figure 2

Finally, you must appreciate that this process can’t be rushed. Your willingness to help is great, but you need to make sure every encounter is a quality one. As you show that you are adding value, the veil will slowly be pulled back as you are introduced to more people who have influence with the coach. Such a process is a great way to network and who knows, it could open up job opportunities in the future.

[optin-monster slug=”nhpxak0baeqvjdeila6a”]