Contents

- What is the sit and reach test?

- What are the benefits of the sit and reach test?

- What does the sit and reach test measure?

- What is the procedure for the sit-and-reach test?

- What is a good sit-and-reach score?

- Conclusion

- References

What is the sit and reach test?

The sit and reach test (SR) is a widely used flexibility assessment that coaches, scientists, fitness professionals and teachers can use to evaluate the degree of movement available at both the hamstring and lower back in members of the public or athletes. Established in 1952 by Katharine Wells and Evelyn Dillon, the SR was introduced as a novel way for those working with athletes to monitor the levels of flexibility between participants in a quick and efficient manner (1). The SR was deemed an appropriate replacement for the former bobbing test, as issues with reliability and validity were consistently reported by those undertaking them. As a result of this, the SR would become one of the most internationally recognised methods utilised when looking to assess the flexibility status of an individual and is still used by many to distinguish where their players rank against their peers or compare nationally.

The SR requires participants to gradually flex at the lumbar and thoracic spine, followed closely by the hip (pelvis) with the “reach” measured as a point of reference. The SR remains popular in many health-related studies, as maintaining hamstring and lower back flexibility may prevent acute and chronic back issues, poor posture, gait limitations and risk of falling (2).

What are the benefits of the sit and reach test?

The SR is a field test used to measure flexibility at the hamstring and lower back. Many studies use the SR, as these are typically inexpensive and easy to collect. For example, a competent practitioner could complete two tests in 60 seconds, allowing them to collect large data sets in a short time. With more equipment and a familiarisation protocol in place, a whole cohort of 30-60 athletes could be screened within one hour. This is particularly useful for sports scientists or teachers, who are typically allotted short periods of time to conduct such testing. In addition, training practitioners to collect this data, is relatively easy and cheap, lending to the popularity of this test amongst many disciplines.

In following the correct protocol, individuals are asked to “sit” and “reach” as far as possible on the SR box. Their ability to reach far is one way that participants can be judged in terms of their flexibility. As well as the reach distance, which is often taken in centimetres, those collecting the data can also visually scan the movement, highlighting deficits at the hamstring (e.g. an inability to straighten the legs), or overhead mobility (e.g. lack or overhead extension when flexing at the hip).

What does the sit and reach test measure?

As mentioned above, the SR is used to measure flexibility at the hamstring and lower back. This is particularly important for those working with athletes, as hamstring injuries are common in team sports athletes. For example, in a recent meta-analysis, Maniar and Colleagues (3) found that hamstring injuries represented roughly 10 % of all injuries in field-based team sports. Moreover, 13 % of athletes experienced a hamstring injury over a 9-month period, calling for more preventative strategies to be implemented within sports settings. In a more recent study, Cai et al., (2023) found that acute bouts (i.e. 6 weeks) of hamstring flexibility training was significant at reducing injury (4). Therefore, coaches must consider the impact of poor flexibility on injury, and monitor this variable with their athletes.

When assessing back pain, this injury is common in both athletes and the general public, with roughly 7.5 % of the world’s population suffering from back pain (5). When an athlete presents reasonable levels of flexibility, muscles are better prepared to deal with the load of sport or daily life. For the general public, this injury also presents a socioeconomic burden by impairing an individual’s ability to function and work.

Outside of the logistical considerations, those who adopt the sit and reach test may use this test for a host of reasons. One factor that practitioners may wish to investigate is the degree of extension available to an individual at the hip. For example, a lack of extension at the hamstring can decrease pelvic mobility (6) In turn, an individual with such deficits is susceptible to a host of biomechanical issues such as; thoracic hyperkyphosis, spondylolysis or changes in gait (7,8). For the general public, any change to the proper function and/ or alignment of the spine can result in lower back pain, increased risk of falls, and difficulty completing jobs such as manual labour. From the perspective of an athlete, such issues can impact performance, limiting an athlete’s ability to express force, whilst increasing injury risk.

What is the procedure for the sit and reach test?

Although there are many ways that athletes are asked to perform the SR test, the most common methods are as follows:

- The athlete/member of the public performs a dynamic warm-up, similar to those used in a RAMP protocol (9).

- Following the warm-up, subjects should be given a visual demonstration of the test, allowing them to ask questions to overcome any misconceptions related to the test or ask for further elaboration. This demonstration should reinforce the need to keep the knees straight throughout the test.

- Those being tested should remove their shoes, to overcome any issues that may impact both the validity or reliability of the test. Following this, they should be encouraged to place the soles of their feet at the base of the sit and reach the box, straighten their legs and sit in an upright position.

- When looking down towards the box, the feet should be symmetrical, with the heels roughly 20 cm apart. The participant should place one hand on top of the other and slowly reach forward as far as possible.

- Movement should be smooth with little bouncing, with encouragement to hold the position for at least 2 seconds. These steps can be repeated three times to generate a mean score or best score.

In addition to the “typical” SR test, there are a few variations which can be seen below that can also be used when looking to assess flexibility. Alternatives are provided for many reasons, including; ease of use, appropriateness, or competence, but each variation may have more applicability to the participant. These consist of:

- The Back-saver sit and reach test, is designed to test hamstring extensibility, with only one leg assessed. This protocol is safer on the spine as it restricts intervertebral flexion and can assess hamstring asymmetry (10).

- The V-Sit and Reach Test requires no SR box but instead requires participants to reach as far forward to a measure on the floor. In addition, some subjects may need some support from others to keep their knees on the floor. The advantages of this test are that it requires little to no equipment, coupled with a simple procedure that many can use.

- The modified SR test is a popular version of the SR test, as this accounts for differences in an individual’s anthropometry (e.g. longer legs or arms), which in turn can give false measurements. Participants are instructed to place their backs against a wall and reach forward to the box. This measurement is taken as their “zero”. Then, participants are invited to perform the normal sit and reach test, with their initial measure (i.e. “zero”) as their start point (11).

What is a good sit and reach score?

When investigating normative data, what is “good” for one athlete or member of the public may not be good for another. For example, a gymnast should be expected to have greater levels of flexibility than that of a football player. Nevertheless, there are a host of reasons that may impact flexibility, such as:

- Age

- Gender

- Ethnicity

- Previous training experience

- Anthropometry (e.g. restrictions at the hip capsule)

- Previous injury

- Muscle fibre type

- Sport (12)

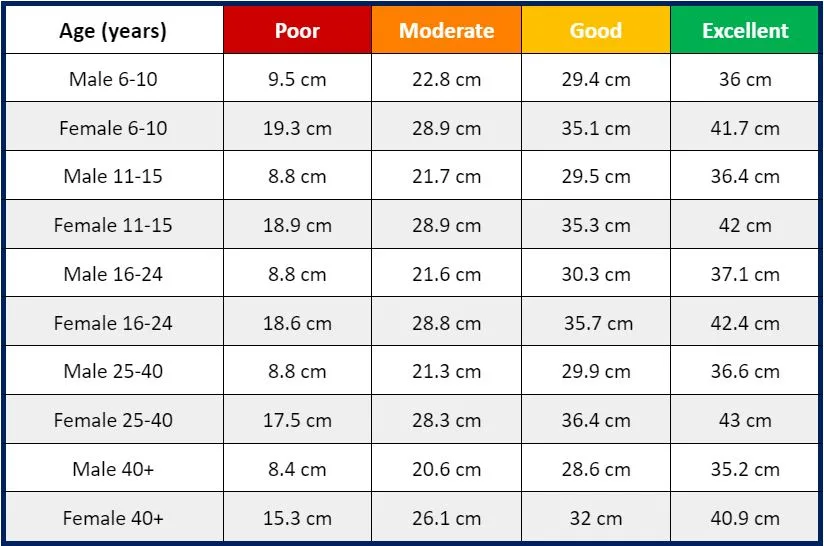

As a result, those performing the SR test should be objective between participants, whilst remaining mindful of any assumptions they may have. In addition, the sit and reach test can be a valid screen for other conditions such as hypermobility or various spine disorders (e.g. kyphosis), which can be useful to refer the patient to relevant support networks. With regards to normative data, the table below highlights a scoring system that you could use with your athlete/member of the public:

Table 1. Sit and reach performance values by age group and sex, adapted from Hoffman et al., (2019) with performance ranking applied as an example.

The SR test reports consistently high levels of reliability in both males and females (0.96 < 0.99) (14), justifying its continued use to gain quick and useful information for those assessed.

Conclusion

The SR test remains useful when assessing flexibility at the hamstring and lower back in athletes and members of the public and provides a low-cost, easy-to-administer protocol that can be delivered to large groups. Although advancements in sports science and technology allow those at the “gold standard” of testing to gain more useful information about a muscle’s architecture (e.g. x-ray, ultrasound and surface electromyography), the SR test may still be useful for those with a smaller budget.

- Katharine F. Wells & Evelyn K. Dillon (1952) The Sit and Reach—A Test of Back and Leg Flexibility, Research Quarterly. American Association for Health, Physical Education and Recreation, 23(1); 115-118. [Link]

- American College of Sports Medicine. (2013). ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Link]

- Maniar, N., Carmichael, D. S., Hickey, J. T., Timmins, R. G., San Jose, A. J., Dickson, J., & Opar, D. (2023). Incidence and prevalence of hamstring injuries in field-based team sports: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 5952 injuries from over 7 million exposure hours. British journal of sports medicine, 57(2); 109-116. [Link]

- Cai, P., Liu, L., & Li, H. (2023). Dynamic and static stretching on hamstring flexibility and stiffness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon, 9(8); e18795. [Link]

- Albasseet, A. O., Abubaker, S., Mandourah, M., Alsaud, A., Alfadda, M., Almutairi, F. E., & Rayes, Z. (2023). Prevalence of Low Back Pain Among Athletes in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Surgery and Medicine, 9(1); 37-37. [Link]

- da Silva Dias, R., & Gómez-Conesa, A. (2008). Shortened hamstring syndrome. Fistioterapia-Barcelona, 30(4); 186-193. [Link]

- Radwan, A., Bigney, K. A., Buonomo, H. N., Jarmak, M. W., Moats, S. M., Ross, J. K., Tatarevic, E., & Tomko, M. A. (2014). Evaluation of intra-subject difference in hamstring flexibility in patients with low back pain: An exploratory study. Journal of back and musculoskeletal rehabilitation, 28(1); 61-66. [Link]

- Salemi, P., Shadmehr, A., & Fereydounnia, S. (2021). The Immediate Effect of Static Hamstring Stretching on Dynamic Balance and Gait Biomechanical Variables in Athletes with Hamstring Tightness: A Preliminary Study. Journal of Modern Rehabilitation, 15(3); 141-150. [Link]

- Jeffreys, I. J. U. J. (2006). Warm up revisited–the ‘ramp’ method of optimising performance preparation. UKSCA Journal, 6; 15-19. [Link]

- López-Miñarro, P. A., de Baranda Andújar, P. S., & RodrÑGuez-GarcÑa, P. L. (2009). A comparison of the sit-and-reach test and the back-saver sit-and-reach test in university students. Journal of sports science & medicine, 8(1); 116. [Link]

- Minkler, S., & Patterson, P. (1994). The validity of the modified sit-and-reach test in college-age students. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 65(2); 189-192. [Link]

- Gleim, G. W., & McHugh, M. P. (1997). Flexibility and its effects on sports injury and performance. Sports medicine, 24; 289-299. [Link]

- Hoffmann, M. D., Colley, R. C., Doyon, C. Y., Wong, S. L., Tomkinson, G. R., & Lang, J. J. (2019). Normative-referenced percentile values for physical fitness among Canadians. Health Rep, 30(10); 14-22. [Link]

- Jackson, A., & Langford, N. J. (1989). The criterion-related validity of the sit and reach test: replication and extension of previous findings. Research quarterly for exercise and sport, 60(4); 384-387. [Link]