Contents of Article

- Summary

- Introduction

- How does body composition affect performance?

- What are Skinfold Calipers?

- How to Calculate Body Fat Percentage?

- Validity and Reliability of Skinfold Calipers

- Technical Error of Measurement (TEM)

- Conclusions

- References

Summary

Measurement of body composition is essential for both health-related measures and performance-enhancing reasons in sport. Although there are numerous ways to measure body composition, the method of skinfold calipers for estimating body composition is often disregarded as a good choice.

Many things can affect the accuracy of the measurement of body composition using calipers, including the equipment, the level of expertise of the tester, and which equation is used for prediction, however, skinfold calipers can still offer a relatively accurate and quick, affordable way to measure body composition changes over time.

Introduction

Kinanthropometry is the study of human size, shape, proportion, composition and function. The purpose of kinanthropometry is to understand human growth, performance, and nutritional status, especially concerning sports performance. Kinanthropometry techniques have been used for centuries to measure the physique of athletes and other individuals alike and include techniques such as somatotyping, anthropometric techniques, and body composition testing (3).

- Somatotyping involves a visual appraisal and ranking on a scale consisting of ectomorphy, endomorphy, and mesomorphy.

- Body composition testing comprises of measurements of body mass, fat-free mass, and fat mass.

- Anthropometry uses girths, skinfolds, bony widths, and lengths to get more information about the athlete’s physique (16).

Currently, the Level 3 Anthropometrist course delivered by the International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry (ISAK) is the highest international standard for kinanthropometry (17). Although the organisation has thousands of members and holds itself to a high standard of excellence, professionals in the field of sports science and strength and conditioning are not legally required to hold an ISAK certification to provide anthropometric services.

There are numerous ways to measure body composition, including, but not limited to, body mass index (BMI), underwater weighing, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), air-displacement plethysmography, skinfold calipers, or somatotyping. Currently, the absolute gold standard for body composition measurement is cadaver analysis (2, 21), as no other in-vivo technique will be as accurate as the dissection technique. In living subjects (in-vivo), however, DEXA is currently seen as the gold standard.

- Where does that leave skinfold calipers?

- Are they perhaps inaccurate or even overused in the fitness and sport science industries?

In this article, the advantages and shortcomings of the skinfold calipers as a means of estimating body composition will be thoroughly discussed.

How does body composition affect performance?

Depending on the physiological demands of the sport, anthropometry could be one of the key performance indicators in competition, as it is in sport climbing. Many studies have highlighted the importance of a low percentage of body fat for good climbing performance and therefore is measured routinely in testing batteries (13). In this case, DEXA and skinfolds might be used jointly so that both accurate numbers of actual body fat percentage through DEXA, and more frequent check-ins with an ISAK-certified specialist for skinfolds could be used.

Similarly, a key performance indicator for marathon events or long-distance running is a low body fat percentage, which is crucial in planning the yearly periodisation for the athletes in and out of their main competition seasons (4). For an event like the marathon, in which the athletes carry their body weight, having a low body fat percentage, and low total body weight will decrease the energy cost of running, further contributing to their performance (19).

What are skinfold calipers?

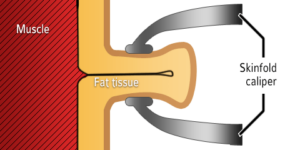

Skinfold calipers (Figure 1) are one instrument used by anthropometrists (specialists that study kinanthropometry) to attempt to estimate the amount of fat on a human body. There are many different shapes and prices for skinfold calipers, but ISAK does not specify which caliper types are required, so often what the budget affords are the ones practitioners choose.

Common plastic calipers, SlimGlides for example, can be purchased online for under $40 USD, and are accurate to the nearest 0.5 mm (15). Harpendens, by contrast, can cost hundreds of dollars, are made of metal, and have a measurement accuracy to the nearest 0.1 mm (15, 17).

As long as calipers are properly calibrated, then they may be used for estimating body fat (21). By taking a double fold of the skin and underlying subcutaneous fat with the skinfold caliper (Figure 2), practitioners measure various specific sites on the body to estimate the average thickness of each site.

With this information, scientists have developed equations that help us estimate the total body fat percentage. Matiegka was the first to develop equations for predicting body fat percentage from skinfold thickness (17). Since then, numerous equations have been developed (21).

How to calculate body fat percentage?

Though many equations have been developed in an attempt to improve the measurement accuracy of skinfold calipers, the following equations were developed by Siri (1961). These equations are just one example of how this can be done, however, other equations are specifically targeted to gender, age group, and other types of populations (e.g. sport-specific).

Body Density (men) = 1.112505 – 0.0013125 * X3 + 0.0000055* (X3) ^2 – 0.000244*age

Where X3 is the sum of the following skinfolds: triceps, chest, and subscapular.

Body Density (women) = 1/089733 – 0.0009245*X3 + 0.0000025*(X3) ^2 – 0.0000979*age

Where X3 is the sum of the following skinfolds: triceps, supra-illiac, and abdominal. (Age is always in years).

Once the body density has been determined, the percentage of fat mass (body fat percentage) is calculated by applying equations of Siri (16):

Percent fat = ((4.95/Body Density))-4.5) * 100.

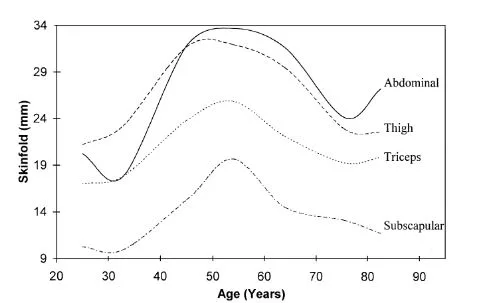

Most predictive equations have a standard error of estimate (SEE) from ± 3 % to ± 7 %. For example, common equations used alongside skinfolds like Jackson and Pollock, or Durnin and Womersley’s sex- and age-specific equations, all produced similar percentage body fat percentages to DEXA and underwater weighing (UWW) techniques as seen in Figure 3 but did tend to under-predict on average.

Validity and Reliability of Skinfold Calipers

As skinfold calipers are quick, easy-to-use, and very affordable for estimating body fat percentage, they have become more widely used over the years (21). This has happened despite newer techniques such as DEXA, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computerized tomography (CT), and bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) all having been developed (20).

One study by Eston et al. (2005) (7) investigated the relationship between body fat percentage, measured by skinfolds, versus DEXA, and found that skinfolds were “highly related to the percent body fat in fit and healthy young men and women”; especially the thigh skinfold, which showed the highest correlation with total percent fat.

Another study evaluating the validity of body fat measured by skinfolds, ultrasound, and BIA compared to DEXA, found that in 208 young men and women, skinfolds were highly correlated to DEXA results (r = 0.91-0.92), with a mean difference between both measures of 6.9 ± 0.4 percent body fat (6). Furthermore, skinfolds tended to under predict body fat percentage as compared to DEXA, revealing that DEXA and skinfold could not be used interchangeably. According to this study, and others (6, 9), skinfolds may have a significant bias at extremes of body fat and age.

The best use of skinfolds seems to be their raw values (i.e. the summation of all measurement sites in millimetres), rather than their ability to predict total body fat percentage because there are errors associated with the accuracy of the collection of the raw data, and error in assumptions in the final values (21). Raw skinfold data can give us a good idea of the regional fatness, unlike other measures like BMI or circumference measures alone (8, 21).

For some populations, such as athletic populations, where the difference of one percentage point of body fat can make a difference in performance, skinfolds are likely more important (12). For overweight or obese populations, taking skinfolds may be of less use, as accuracy and reliability of the skinfold measurements will be harder to repeat as the skinfold thickness increases, so methods like DEXA may be more accurate (5). Other studies, for example on obese children, have found good agreeance between skinfolds and percent fat measured by DEXA (22), however, considerations based on the population being measured must be addressed by each case separately.

Technical Error of Measurement (TEM)

As with any good science, if the experiment can be repeated many times over (repeatability),and is valid (the attempt to measure what we think we’re measuring, otherwise known as accuracy), the research is likely good research and helps contribute to our better understanding of a topic.

In anthropometry, technical error of measure (TEM) is what we refer to the error that occurs when a measurement is taken on the same object more than once, and the values are not the same. This error is inherent especially when humans are involved in the measurements, due to:

- Biological variation of the subject (day-to-day)

- Biological variation of the subject (within-day)

- Instrument fault (not calibrated properly or not functioning properly), or

- Human measurement fault (intra- and inter-tester error)

- Environment (change of testing site setting or location)

We want to minimise the error in our measurement as much as possible to create the most accurate and reliable measurement possible each time, but all errors cannot usually be removed (11). To minimise these factors, it is best that we control as many factors as possible, and use the same tester, the same location, the same time of day and day of the week, and a consistent schedule throughout the week (in training and diet) (11).

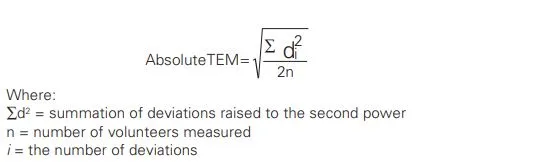

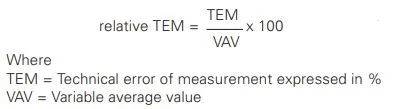

Because we know the error is associated with the measurements, practitioners should always express their measures as a value with the technical error, so that when measuring change over time, we can be more certain of real change versus errors made in measuring. To calculate the technical error, use the following equations, outlined in a paper by Perini et al. (11):

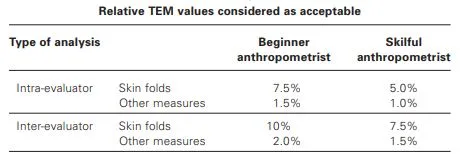

Table 1. Acceptable levels for intra- and inter-evaluator error, according to a beginner (Level 1 ISAK) versus a skilful anthropometrist (Level 4 ISAK) (10).

Finally, to make measurements of body composition more accurate, ensure the use of predictive body fat percentage equations that best match the demographic of the persons tested.

Conclusion

Generally, the understanding of the use of skinfold calipers and their accuracy is very poor and grossly misunderstood. Given this, our mission was to clarify whether skinfolds are a good method of choice for body composition.

In conclusion, skinfold calipers can be a cost-effective, quick, and relatively accurate measure of body composition over time. While the gold standard for body composition is still cadaver dissection, skinfold measurements can offer information about the relative fatness, the change in body composition over time, and potentially even the health of the individual.

Knowing that increased fat mass is associated with various diseases, and some athletes need specific body fat percentages for optimal performance, it is of importance that fitness professionals measure skinfolds accurately and with the ability to be repeatable, following the ISAK for best results.

- Alva, M. (2008). ‘Body composition techniques in obesity’. Arq Sanny Pesq Saúde, 1(2); 141-154.

- Armstrong, L. E. (2007). Assessing Hydration Status: The Elusive Gold Standard. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 26(sup5), 575S–584S. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2007.10719661

- Barbieri, D., Gualdi-Russo, E., Zaccagni, L. (2011). Kinanthropometry and Sport Practice. Universita degli Studi di Ferrara.

- Burke, L. M. (2007). Nutrition Strategies for the Marathon Fuel for Training and Racing, 37, 344–347.

- Donini, L. M., Poggiogalle, E., Del Balzo, V., Lubrano, C., Faliva, M., Opizzi, A., … Rondanelli, M. (2013). How to estimate fat mass in overweight and obese subjects. International Journal of Endocrinology, 2013, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/285680

- Duz, S., Kocak, M., & Korkusuz, F. (2009). Evaluation of body composition using three different methods compared to dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. European Journal of Sport Science, 9(3), 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461390902763425

- Eston, R. G., Rowlands, A. V, Charlesworth, S., Davies, A., & Hoppitt, T. (2005). Prediction of DXA-determined whole body fat from skinfolds: importance of including skinfolds from the thigh and calf in young, healthy men and women. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 59(5), 695–702. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602131

- Jackson, a S., Pollock, M. L., Graves, J. E., & Mahar, M. T. (1988). Reliability and validity of bioelctrical impedance in determining body composition. Journal of Applied Physiology, 64(2), 529–534.

- Lean, M., Han, S, Deurenberg, P. (1996). Predicting body composition by densitometry from simple anthropometric measurements. AMerican Journal of Clinical Nutritiom, 63, 4–14.

- Norton, K., Olds, T., Olive, S., Craig, N. (2000). Anthropometrica: A Textbook of Body Measurement for Sports and Health Courses. (Australian Sport Commission, Ed.). Sydney, Australia.: University of New South Wales Press LTD. Retrieved from https://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=Bkk8FuB0P4IC&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=gore+2000+kevin+norton+tim+olds&ots=u6VwL6Mpr_&sig=XbUIpA_KAfcD4P-xVkwc7vKOfKU#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Perini, T. a, de Oliveira, G. L., Ornelia, J. S., & de Oliveira, F. P. (2005). Technical error of measurement in anthropometry. Revista Brasileira de Medicina Do Esporte, 11, 81–85. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1517-86922005000100009

- Ransdell, L. B., & Murray, T. (2011). A physical profile of elite female ice hockey players from the USA. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 25(9), 2358–2363. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e31822a5440

- Romero, V. E., Ruiz, J. R., Ortega, F. B., Artero, E. G., Vicente-Rodríguez, G., Moreno, L. A., … Gutierrez, A. (2009). Body fat measurement in elite sport climbers: Comparison of skinfold thickness equations with dual energy X-ray absorptiometry. Journal of Sports Sciences, 27(5), 469–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410802603863

- ScienceduSport.com (2014). Follow up your progress using a technique to measure the muscle cross-sectional area. Retrieved from www.sci-sport.com/en/articles/Follow-up-your-progress-using-a-technique-to-measure-the-muscle-cross-sectional-area-019.php on March 31, 2020.

- Schmidt, P. K., Carter, J. E. L. (1990). Static and Dynamic Differences among Five Types of Skinfold Calipers Author ( s ): Paul K . Schmidt and J . E . L. Carter. Journal of Human Biology, 62(3), 369–388.

- Siri, W. E. (1961). Body composition from fluid spaces and density: analysis of methods. Techniques for Measuring Body Composition. Washington: National Academy of Sciences, 224–44.

- Stewart, A., Marfell-Jones, M., Olds, T., de Ridder, H. (2011). International Standards for Anthropometric Assessment. International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry.

- Souffir, C. (2016). Évaluation de la mesure de la graisse viscérale abdominale dans les rhumatismes inflammatoires chroniques (polyarthrite rhumatoïde et spondyloarthropathies). Médecine humaine et pathologie.

- Tanda, G., & Knechtle, B. (2013). Marathon performance in relation to body fat percentage and training indices in recreational male runners. Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine, 4, 141–9. https://doi.org/10.2147/OAJSM.S44945

- Topend Sports (2008). Skinfold Caliper Guide. Retrieved from : https://www.topendsports.com/testing/skinfold-caliper-guide.htm on March 31, 2020

- Wang, J., Thornton, J. C., Kolesnik, S., & Pierson, R. N. (2006). Anthropometry in Body Composition: An Overview. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 904(1), 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06474.x

- Wells, J. C. K. (2005). Measuring body composition. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 91(7), 612–617. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2005.085522

- Wohlfahrt-Veje, C., Tinggaard, J., Winther, K., Mouritsen, A., Hagen, C. P., Mieritz, M. G., … Main, K. M. (2014). Body fat throughout childhood in 2647 healthy Danish children: agreement of BMI, waist circumference, skinfolds with dual X-ray absorptiometry. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 68(6), 664–670. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2013.282