Contents of Article

- Summary

- What is the reactive strength index (RSI)?

- Why is the reactive strength index important for sports?

- How do you calculate the reactive strength index?

- Is the reactive strength index valid and reliable?

- Are there any issues with the reactive strength index?

- Is future research needed on the reactive strength index?

- Conclusion

- References

- About the Author

Summary

The reactive strength index was developed to measure the reactive jump capacity of athletes and to determine how they cope with the stress imposed on their body from plyometric exercises. Reactive strength is related to acceleration speed, change of direction speed, and even agility. There are many valid and reliable tests used to measure the reactive strength index – the most common of which is the incremental drop jump test.

The ground contact time of the reactive strength index test is an important parameter that must be considered when testing athletes and especially for interpreting the information. It is suggested athletes must have a sound level of technical plyometric proficiency before they are even considered for testing.

For procedures on how to conduct a Reactive Strength Index test, click here.

What is the reactive strength index (RSI)?

The reactive strength index (RSI) was originally developed as part of the Strength Qualities Assessment Test (SQAT) developed by the Australian Institute of Sport (1) which consists of:

- Maximum strength

- High-load speed-strength (> 30 % of max)

- Low-load speed-strength (< 30 % of max)

- Rate of force development

- Reactive strength (change of movement from rapid eccentric to rapid concentric)

- Skill performance (coordination of the muscle contractions in a sports-specific action)

It was originally developed using an incremental drop-jump (DJ) as the testing exercise as it was reported to be only the plyometric exercise with an identifiable ground contact time (2). Since then, advancements in both research and technology have been made, thus various other tests have been developed to measure RSI. The current RSI tests include:

- Incremental DJ-RSI test (1) [original test]

- Countermovement Jump test (2)

- Tuck Jump test (2)

- Single-Leg Jump test (2)

- Squat Jump test (2)

- Dumbbell Countermovement Jump test (2)

- 10/5 test (3)

- Vertical Rebound Jump test

- Single Rebound Jump (4)

- Vertical Rebound for 10 seconds (5)

- Vertical Rebound for 5 repetitions (6)

- Vertical Rebound for 15 repetitions (7)

The RSI was developed to measure how an athlete copes and performs during plyometric activities by measuring the muscle-tendon stress and their reactive jump capacity (8). It demonstrates an athlete’s ability to rapidly change from an eccentric motion into a concentric muscular contraction and is an expression of their dynamic explosive vertical jump capacity (1).

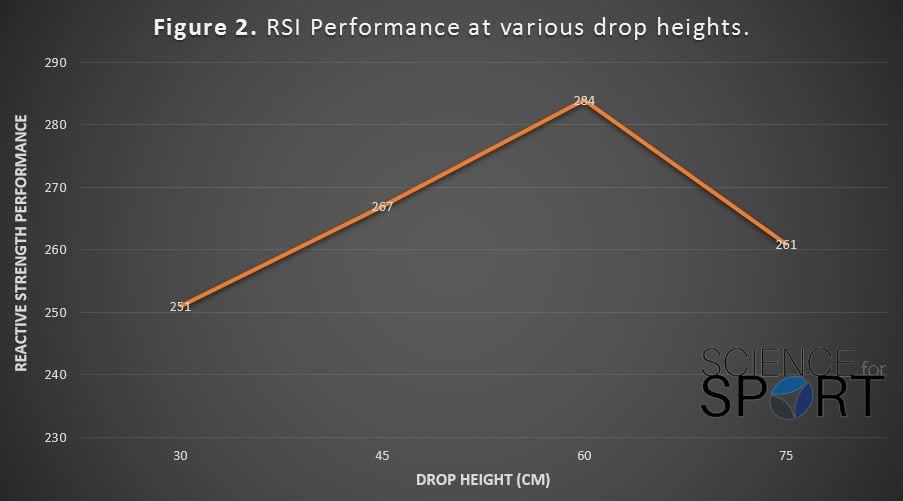

The incremental DJ-RSI can also be used to provide recommendations for an athlete’s optimal drop height for plyometric exercises (9). Figure 1 provides a clear example of a performance drop-off after a given drop height – in this case at 80 cm. This suggests that the athlete’s ‘optimal’ box height for a DJ is 60 cm.

Furthermore, as well as being a useful marker for measuring performance and training progress, the RSI tests are also commonly used to measure neuromuscular fatigue during competition periods in team sports (10, 11).

Why is the reactive strength index important for sports?

As the RSI demonstrates an athlete’s ability to quickly and effectively change from an eccentric to a concentric contraction, it, therefore, represents their ability to utilise the stretch-shortening cycle and their explosive capabilities during dynamic jumping activities (8). An athlete’s ability to quickly and effectively move through the stretch-shortening cycle is important for a variety of sports.

For example, taking off in the long jump, or even changing direction in football both require the athlete to rapidly move through the stretch-shortening cycle. In fact, the RSI has been shown to have a strong relationship with both change of direction speed and acceleration speed (12). To add to this, recent research has also identified strong relationships between reactive strength and offensive and defensive agility in Australian football players (13). As a result, it appears reactive strength is an important physical quality for acceleration, agility, and change of direction speed.

How do you calculate the reactive strength index?

There are three common methods to calculate the performance of the RSI test. These are:

- Method 1: RSI = Jump Height / Ground Contact Time

- Method 2: RSI = Flight Time / Ground Contact Time

- Method 3: RSI = Jump Height / Time to Take-off

Jump height is an estimate of the height change in the athlete’s centre of mass. Jump height is best measured using the velocity data from a force platform. This can be calculated using the following formula:

Jump Height = 9.81 * (flight time)2 / 8

Flight time is quite simply the total time the athlete is in the air during a jump – from when they break contact with the floor, to when they first touchdown upon landing. This is often measured using a jump/ contact mat, however, results can be easily influenced by body position during take-off and landing. For example, if an athlete bends their legs during flight, this can alter the results and affect the accuracy of the test.

Time to take-off includes the eccentric and concentric phases of the stretch-shortening cycle (2).

Though both jump height and flight time can be measured directly and accurately, numerous professionals prefer to use flight time as opposed to jump height because it is easier to obtain and less time-consuming. It makes little difference which calculation is used as jump height and flight time are strongly correlated as both are a straight mathematical derivation (14). If using a force plate, it is better to use jump height based on ground reaction forces as this has been suggested to provide a more valid RSI measure. If no force plate is available, then using flight time calculated from a contact mat also works well and is often used in research and practice settings.

Is the reactive strength index valid and reliable?

The RSI has been proven to be a valid and reliable measure of reactive jump capacity, though it is important to understand that there is no “gold-standard” test for the RSI to be compared to. Nonetheless, the following tests have been proven to be valid and reliable measures of RSI:

- Incremental DJ-RSI test (15)

- Modified RSI test (2)

- Single Vertical Rebound Jump test (4)

- Vertical Rebound Jump for 5 repetitions (6)

- 10/5 test (3)

Lastly, as both flight time and jump height are reliable measures with a strong correlation, either can be used with confidence to calculate RSI.

Are there any issues with the reactive strength index?

The duration of the ground contact time

One of the primary issues with the RSI is the duration of the ground contact time of the test used. For example, the ground contact time during the DJ can range between 130-300 ms (16, 17). As the ground contact time of many sporting movements can be significantly less than this (Table 1), there are concerns regarding the test’s ability to actually measure sport-specific reactive strength.

| Drop height (cm) | Jump height (cm) | Contact time (s) | RSI performance (jump height/time) |

| 30 | 38.9 | 0.155 | 251 |

| 45 | 40.8 | 0.153 | 267 |

| 60 | 40.1 | 0.141 | 284 |

| 75 | 37.1 | 0.142 | 261 |

Therefore, using the incremental DJ-RSI test may not be a useful test for sprinters, as their ground contact times are significantly faster. In this instance, alternative RSI tests such as the 10/5 may be more applicable due to the shorter ground contact times and the higher frequency of jumps. Practitioners should be well aware of this issue when testing their athletes and pick a test that better suits the demands of their athletes.

Technical Proficiency

This is another issue that potentially affects both performance testing and fatigue monitoring. An athlete with lower technical proficiency (i.e. movement quality) appears to struggle to replicate plyometric activities such as DJs. This means when testing the athlete(s), there is a high degree of variability within the results – suggesting it is important the athlete(s) have a high level of technical proficiency with plyometric movements before they are tested. Though this is only anecdotal, with no research to the author’s knowledge supporting this claim, the information is still valuable.

Is future research needed with the reactive strength index?

With some of the gaps in the current research highlighted, the following projects will provide a valuable contribution to our current understanding of the RSI:

- The relationship between RSI and other physical qualities (e.g. maximal speed and jumping)

- Ground contact times of various plyometric activities so that they can be used to calculate RSI for sport-specific movements

- Plyometric proficiency and its effect on performance/data variability

Conclusion

- The reactive strength index is a measure of reactive jump capacity and displays how an athlete copes with and performs plyometric activities.

- There are currently five known valid and reliable tests used to measure RSI.

- RSI appears to be linked with acceleration, agility and change of direction speed.

- Jump height and flight time can both be used to measure RSI.

- The ground contact time of the RSI test is an important parameter for test selection and when interpreting results.

- Technical proficiency may significantly affect the reliability of the test data.

- Young, W. (1995). Laboratory strength assessment of athletes. New Study Athletics. 10, pp.88–96. [Link]

- Ebben, WP and Petushek, EJ. Using the reactive strength index modified to evaluate plyometric performance. J Strength Cond Res 24(8): 1983–1987, 2010 [PubMed]

- Harper, D. 2011. The 10 to 5 repeated jump test. A new test for evaluating reactive strength. In: British Association of Sports and Exercises Sciences Student Conference, Chester. [Link]

- Flanagan, E.P., 2007, December. An examination of the slow and fast stretch shortening cycle in cross country runners and skiers. In ISBS-Conference Proceedings Archive (Vol. 1, No. 1). [Link]

- CHELLY, S. M., and C. DENIS. Leg power and hopping stiffness: relationship with sprint running performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc., Vol. 33, No. 2, 2001, pp. 326–333. [PubMed]

- Lloyd, R.S., Oliver, J.L., Hughes, M.G., Williams, C.A. (2009). Reliability and validity of field-based measures of leg stiffness and reactive strength index in youths. Journal of Sports Sciences. 27(14), pp.1565-1573. [PubMed]

- Hobara H, Inoue K, Omuro K, Muraoka T, Kanosue K. Determinant of leg stiffness during hopping is frequency-dependent. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011 Sep;111(9):2195-201. [PubMed]

- Flanagan, E.P., Ebben, W.P., and Jensen, R.L. (2008). Reliability of the reactive strength index and time to stabilization during depth jumps. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 22(5), pp.1677–1682. [PubMed]

- McClymont, D. (2003). Use of the reactive strength index (RSI) as an indicator of plyometric training conditions. In: Proceedings of the 5th World Conference on Science and Football. pp. 408–416. [Link]

- Cormack, S.J., Newton, R.U., McGuigan, M.R. and Cormie, P., 2008. Neuromuscular and endocrine responses of elite players during an Australian rules football season. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform., 3(4). [PubMed]

- Hamilton, D., 2009. Drop jumps as an indicator of neuromuscular fatigue and recovery in elite youth soccer athletes following tournament match play. Journal of Australian Strength and Conditioning, 17(4). [Link]

- Young, W.B., Miller, I.R. and Talpey, S.W., 2015. “Physical Qualities Predict Change-of-Direction Speed but Not Defensive Agility in Australian Rules Football.” The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 29(1), pp.206-212. [PubMed]

- Young, Warren B; Murray, Mitch P. Reliability of a field test of defending and attacking agility in Australian football and relationships to reactive strength. Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research: Post Acceptance: May 19, 2016. [Link]

- Garcıa-Lopez, J, Morante, JC, Ogueta-Alday, A, and RodrıguezMarroyo, JA. The type of mat (contact vs. photocell) affects vertical jump height estimated from flight time. J Strength Cond Res 27(4): 1162–1167, 2013 [PubMed]

- Markwick WJ, Bird SP, Tufano JJ, Seitz LB, Haff GG. The intraday reliability of the Reactive Strength Index calculated from a drop jump in professional men’s basketball. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2015 May;10(4):482-8. [PubMed]

- Ball, NB, Stock, CG, and Scurr, JC. Bilateral contact ground reaction forces and contact times during plyometric drop jumping. J Strength Cond Res 24(10): 2762–2769, 2010] [PubMed]

- Walsh, M., A. Arampatzis, F. Schade, and G.-P. Bruggemann. The effect of drop jump starting height and contact time on power, work performed, and moment of force. J. Strength Cond. Res. 18(3):561–566. 2004 [PubMed]

- Padulo, J, Annino, G, D’Ottavio, S, Vernillo, G, Smith, L, Migliaccio, GM, and Tihanyi, J. Footstep analysis at different slopes and speeds in elite race walking. J Strength Cond Res 27(1): 125–129, 2013 [PubMed]

- Taylor, M. J. D., & Beneke, R. (2012). Spring Mass Characteristics of the Fastest Men on Earth.International journal of sports medicine, 33(8), 667. [PubMed]

- Laffaye, G, Wagner, PP, and Tombleson, TIL. Countermovement jump height: Gender and sport-specific differences in the forcetime variables. J Strength Cond Res 28(4): 1096–1105, 2014 [PubMed]

- Stefanyshyn, D. & Nigg, B. (1998) Contribution of the lower extremity joints to mechanical energy in running vertical jumps and running long jumps. Journal of Sport Sciences, 16, 177-186. [PubMed]