Contents of Article

- Summary

- What is the Incremental DJ-RSI test?

- How do you conduct the Incremental DJ-RSI Test?

- How is the Incremental DJ-RSI Test scored?

- Considerations for using the Incremental DJ-RSI Test

- Is the Incremental DJ-RSI Test valid and reliable?

- Are there any issues with the Incremental DJ-RSI Test?

- References

- About the Author

Summary

The Incremental Drop Jump Reactive Strength Index (DJ-RSI) Test was developed to measure the reactive jump capacity of athletes and to determine how they cope with the stress imposed on their bodies from plyometric activities. The ability to quickly and effectively transition from an eccentric to a concentric contraction is a physical quality typically referred to as ‘reactive strength’. Thus, this test reports an athlete’s reactive strength index (RSI). Whilst this test does provide a valid, reliable, and useful measure of jumping ability, it is however inherently flawed by its inability to measure very fast and very slow plyometric activities.

What is the Incremental DJ-RSI test?

The Incremental DJ-RSI Test was originally developed as part of the Strength Qualities Assessment Test (SQAT) developed by the Australian Institute of Sport (1) to measure an athlete’s reactive strength. The testing battery they used constitutes of:

- Maximum strength

- High-load speed-strength (>30% of max)

- Low-load speed-strength (<30% of max)

- Rate of force development

- Reactive strength (change of movement from rapid eccentric to rapid concentric)

- Skill performance (coordination of the muscle contractions in a sports-specific action)

The Incremental DJ-RSI involves an athlete performing a drop-jump on a contact mat or force platform. Though the terms ‘drop-jump’ (2, 3) and ‘depth-jump’ (4, 5) are often used interchangeably in both practical and research environments, the term ‘drop-jump’ is preferred as it implies the athlete simply drops from the box.

The test was developed to measure how an athlete copes and performs during plyometric activities by measuring the muscle-tendon stress and their reactive jump capacity (5). It demonstrates an athlete’s ability to rapidly change from an eccentric motion into a concentric muscular contraction and is an expression of their dynamic explosive vertical jump capacity (1).

The index is a useful tool for testing an athlete’s reactive jump capacity, monitoring training progress, and even as a tool for monitoring fatigue. It can also be used to provide recommendations for an athlete’s optimal drop height for plyometric exercises (6). In recent years, many variations of the RSI have been developed which can also be used to evaluate the explosive capacity of other plyometric exercises (7).

If you’d like to learn more about RSI, then read our article on the Reactive Strength Index.

How do you conduct the Incremental DJ-RSI Test?

Testing Procedure

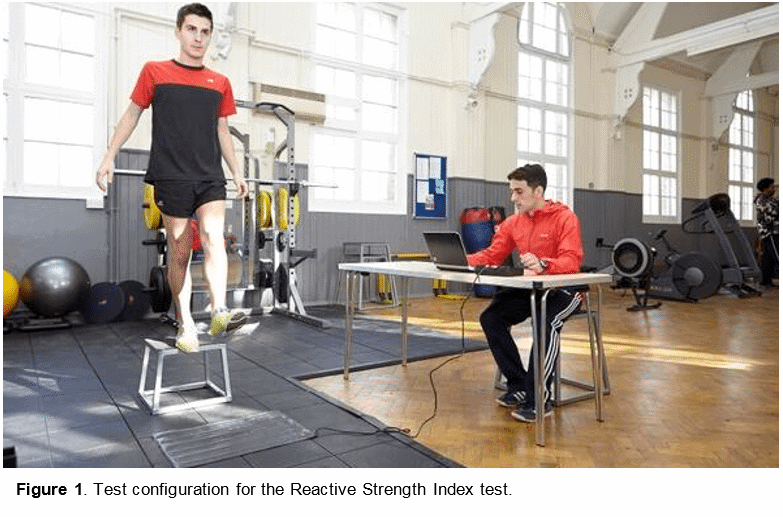

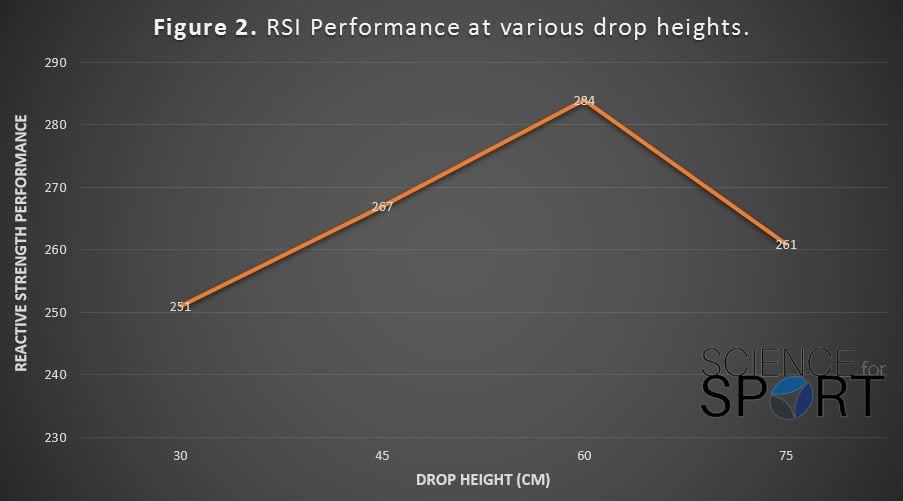

Athletes typically begin the test from the 30cm box and work upwards in a successive order towards the 75cm box. However, the test ends once the athlete’s contact time increases beyond 0.25ms (endpoint of the fast stretch-shortening cycle), whether that is on the 30cm drop jump or the 75cm. Alternatively, the test ends at the moment the athlete’s performance begins to decline (Figure 2).

Whether the athlete places their hands on their hips throughout the test is down to the test administrator’s discretion, as both methods have been shown to be reliable (5). However, it must be understood that similar vertical jump tests have shown that the arm swing can improve performance (8).

Once the test configuration has been set up, and the test official(s) and the athlete are ready, then the test can begin.

- The athlete is instructed to stand on top of the box facing towards the force platform.

- When instructed by the coach, the athlete then steps off the box and performs a typical drop-jump, landing in the same spot as they took off.

- This must be repeated for a minimum of three efforts so a performance average can be calculated.

How is the Incremental DJ-RSI Test scored?

There are three common methods to calculate the performance of the RSI test. These are:

- Method 1: RSI = Jump Height / Ground Contact Time

- Method 2: RSI = Flight Time / Ground Contact Time

- Method 3: RSI = Jump Height / Time to Take-off

Jump height is an estimate of the height change in the athlete’s centre of mass. Jump height is best measured using the velocity data from a force platform. This value can be calculated using the following formula:

- Jump Height = 9.81 * (flight time)2 / 8

Flight time is quite simply the total time the athlete is in the air during a jump – from when they break contact with the floor, to when they first touchdown upon landing. This is often measured using a jump/contact mat, however, results can be easily influenced by body position during take-off and landing. For example, if an athlete bends their legs during flight, this can alter the results and affect the accuracy of the test.

Time to take-off includes the eccentric and concentric phases of the stretch-shortening cycle (7).

Though both jump height and flight time can be measured directly and accurately, numerous professionals prefer to use flight time as opposed to jump height because it is easier to obtain and less time-consuming. It makes little difference which calculation is used as jump height and flight time are strongly correlated as both are straight mathematical derivations (9). If using a force plate, it is better to use jump height based on ground reaction forces as this has been suggested to provide a more valid RSI measure. If no force plate is available, then using flight time calculated from a contact mat also works well and is often used in research and practical settings.

Table 1 and Figure 2 demonstrate how the data is recorded and then displayed.

| Drop Height (cm) | Jump Height (cm) | Contact Time (s) | RSI Performance (jump height/time) |

| 30 | 38.9 | 0.155 | 251 |

| 45 | 40.8 | 0.153 | 267 |

| 60 | 40.1 | 0.141 | 284 |

| 75 | 37.1 | 0.142 | 261 |

Considerations for using the Incremental DJ-RSI Test

When conducting the test there are several factors that need to be taken into consideration before you begin – some being:

- Individual effort – Sub-maximal efforts will result in inaccurate scores.

- Varying take-off and landing positions.

- Participants jumping off the box rather than simply ‘stepping off’.

- Arm-swing or no arm-swing.

Is the Incremental DJ-RSI Test valid and reliable?

The incremental DJ-RSI test has been proven to be a valid and reliable measure of reactive jump capacity (5).

As both flight time and jump height are reliable measures with a perfect correlation, either can be used with confidence to calculate RSI.

Are there any issues with the Incremental DJ-RSI Test?

The duration of the ground contact time

One of the primary issues with the incremental DJ-RSI Test is the duration of the ground contact time of the test used. For example, the ground contact time during the DJ can range between 130-300ms (2, 3). As the ground contact time of many sporting movements can be significantly less than this (Table 2), there are concerns regarding the test’s ability to actually measure sport-specific reactive strength.

| Exercise | Ground Contact Time (Ms) | SSC Classification |

| Race Walking (10) | 270-300 | Slow |

| Sprinting (11) | 80-90 | Fast |

| Countermovement Jump (CMJ) (12) | 500 | Slow |

| Depth Jump (20cm-60cm) (2,3) | 130-300 | Fast/Slow |

| Long Jump (13) | 140-170 | Fast |

| Multiple Hurdle Jumps (5) | 150 | Fast |

Therefore, using the incremental DJ-RSI Test may not be a useful test for sprinters as their ground contact times are significantly faster. In this instance, alternative RSI Tests such as the 10/5 may be more applicable due to the shorter ground contact times and the higher frequency of jumps. Practitioners should be well aware of this issue when testing their athletes and pick a test that better suits the demands of their athletes.

- Young, W. (1995). Laboratory strength assessment of athletes. New Study Athletics. 10, pp.88–96. [Link]

- Walsh, M., A. Arampatzis, F. Schade, and G.-P. Bruggemann. The effect of drop jump starting height and contact time on power, work performed, and moment of force. J. Strength Cond. Res. 18(3):561–566. 2004 [PubMed]

- Ball, NB, Stock, CG, and Scurr, JC. Bilateral contact ground reaction forces and contact times during plyometric drop jumping. J Strength Cond Res 24(10): 2762–2769, 2010 [PubMed]

- Phillips, JH and Flanagan, SP. Effect of ankle joint contact angle and ground contact time on depth jump performance. J Strength Cond Res 29(11): 3143-3148 [PubMed]

- Flanagan, E.P., Ebben, W.P., and Jensen, R.L. (2008). Reliability of the reactive strength index and time to stabilization during depth jumps. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 22(5), pp.1677–1682. [PubMed]

- McClymont, D. (2003). Use of the reactive strength index (RSI) as an indicator of plyometric training conditions. In: Proceedings of the 5th World Conference on Science and Football. pp. 408–416. [Link]

- Ebben, W.P., and Petushek, E.J. (2010). Using the reactive strength index modified to evaluate plyometric performance.Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(8), pp.1983-1987. [PubMed]

- Lees, A., Vanrenterghem, J., & Clercq, D.D. (2006). The energetics and benefit of an arm swing in submaximal and maximal vertical jump performance. Journal of Sports Sciences, 24(1, pp. 51 – 57. [PubMed]

- Garcıa-Lopez, J, Morante, JC, Ogueta-Alday, A, and RodrıguezMarroyo, JA. The type of mat (contact vs. photocell) affects vertical jump height estimated from flight time. J Strength Cond Res 27(4): 1162–1167, 2013. [PubMed]

- Padulo, J, Annino, G, D’Ottavio, S, Vernillo, G, Smith, L, Migliaccio, GM, and Tihanyi, J. Footstep analysis at different slopes and speeds in elite race walking. J Strength Cond Res 27(1): 125–129, 2013 [PubMed]

- Taylor, M. J. D., & Beneke, R. (2012). Spring Mass Characteristics of the Fastest Men on Earth.International journal of sports medicine, 33(8), 667. [PubMed]

- Laffaye, G, Wagner, PP, and Tombleson, TIL. Countermovement jump height: Gender and sport-specific differences in the forcetime variables. J Strength Cond Res 28(4): 1096–1105, 2014 [PubMed]

- Stefanyshyn, D. & Nigg, B. (1998) Contribution of the lower extremity joints to mechanical energy in running vertical jumps and running long jumps. Journal of Sport Sciences, 16, 177-186.[PubMed]