Contents of Article

- Summary

- What is the Dynamic Strength Index?

- Why is the Dynamic Strength Index important?

- How do you calculate the Dynamic Strength Index?

- Is the Dynamic Strength Index valid and reliable?

- How should the Dynamic Strength Index guide your training program?

- References

- About the Author

Summary

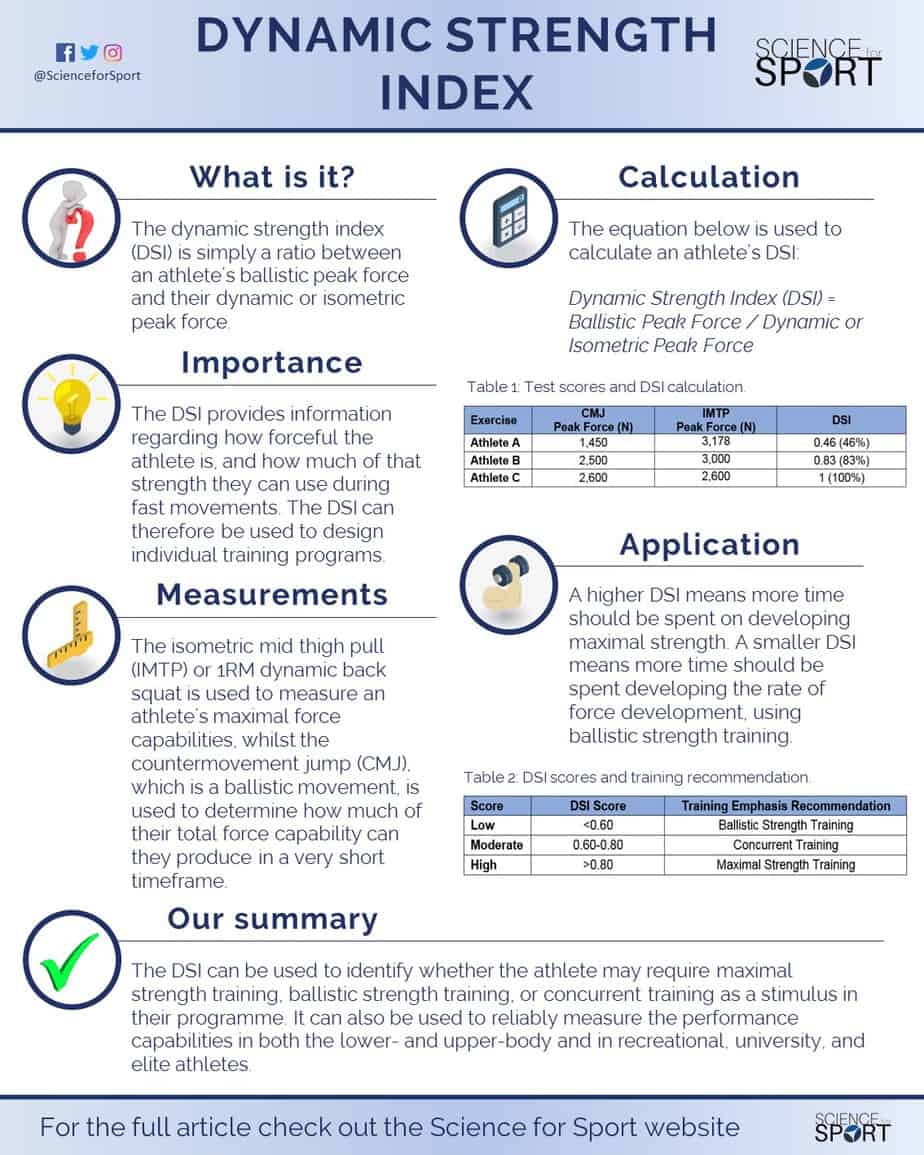

The Dynamic Strength Index, often referred to as the dynamic strength deficit, measures the difference between an athlete’s maximal and explosive strength capacity. However, the term “index” is preferred over “deficit”, as it’s an index of the athlete’s current performance ability. The dynamic strength index can be used to identify whether the athlete may require maximal strength training, ballistic strength training, or concurrent training (i.e. a combination) as a stimulus in their programme. It can also be used to reliably measure the performance capabilities in both the lower- and upper body and in recreational, university, and elite athletes.

What is the Dynamic Strength Index?

The Dynamic Strength Index (DSI), otherwise known as the Dynamic Strength Deficit (1) or the Explosive Strength Deficit (2-4), is simply a ratio between an athlete’s ballistic peak force and their dynamic or isometric peak force (5). In another sense, it may be viewed as a “strength potential” test.

An example of ballistic peak force would be an athlete’s maximal force production during a countermovement jump (CMJ) – as this is a ballistic movement. On the other hand, dynamic peak force may be measured using a 1 repetition maximum (1RM) back squat, whilst an isometric mid-thigh pull (IMTP) may be used to measure their peak force production during an isometric test. It is very common for practitioners to use a CMJ or squat jump (ballistic tests) and an IMTP (isometric test) to calculate an athlete’s DSI (3, 5, 6). Put simply, the DSI measures the difference between an athlete’s ability to produce force during a dynamic or isometric test, versus their ability to produce force during a ballistic exercise. This allows the strength and conditioning coach to identify the athlete’s “strength potential” and how much of that potential they can use during a high-speed ballistic movement.

Calculating the DSI allows the strength and conditioning coach to do two things:

- Determine the maximal amount of force an athlete can produce (e.g. using the IMTP test).

- How much of that total force can they produce in a high-speed movement with a short time frame – i.e. 400 milliseconds (ms) is the time it takes to achieve peak force during the CMJ (7).

Just to clarify, the IMTP or 1RM dynamic back squat is used to measure an athlete’s maximal force capabilities (i.e. maximal strength), whilst the CMJ, which is a ballistic movement, is used to determine how much of their total force capability can they produce in a very short timeframe.

Why is the Dynamic Strength Index important?

The DSI provides the strength and conditioning coach with valuable information regarding how forceful (i.e. strong) the athlete is, and how much of that strength they can use during fast movements. This information allows the coach to design a more specific training programme focussed on developing an athlete’s strength and/or power capacities (6).

The Importance of Maximal Strength

High muscular strength is considered a vital element of athletic performance. Greater muscular strength has been shown to enhance the ability to perform general sports skills such as jumping, sprinting, and change of direction tasks, improve overall performance, allow athletes to potentiate earlier and to a greater extent, and even reduce the risk of injury (8).

To add to this, maximal strength is strongly related to power output (r = 0.77-0.94 [9]) for both the lower- (10-13) and upper body (10, 14-17). Therefore, an athlete’s ability to produce power is largely dependent on their maximal force capacity (i.e. strength) (18-20). As a result, the “first box to be checked” so to speak when performing a strength diagnosis, is perhaps an athlete’s maximal strength.

The importance of being able to produce high force in a short time frame, Kawamori et al. (2006) (7) observed that it took approximately 260 ms to achieve peak force during the IMTP and 400 ms during the CMJ. Other research has shown time to peak force during the CMJ to take approximately 240 ms (21). So whilst the time to achieve peak force during the IMTP (260 ms) can be somewhat similar to the CMJ (240-400 ms), it is in fact how ‘much’ force is developed that separates the two exercises.

Table 1 provides a clear example of how the peak force differs between the IMTP and the CMJ. Thus, the important factor is to determine how much force an athlete can produce under no time constraints (e.g. IMTP) versus how much force they can produce under short time constraints (e.g. CMJ).

| Exercise | Peak Force (N) | Time to Peak Force (ms) |

| IMPT | 3,178 | 260 |

| CMJ | 1,450 | 240-400 |

Below are some examples of common ground contact times during particular sporting movements:

- Basketball lay-up shot = 218 ms (22)

- Sprinting = 80-90 ms (23)

- Long Jump = 140-170 ms (24)

As many sporting movements, such as those above, happen in a very short time frame and are all ballistic in nature, it is vital to analyse the athlete’s ballistic force production capabilities under short time constraints.

How do you calculate the Dynamic Strength Index?

The equation below is used to calculate an athlete’s DSI. And although it is referred to as a “ratio”, it is not displayed as a one and is instead a simple division between ballistic and dynamic or isometric peak forces.

Dynamic Strength Index (DSI) = Ballistic Peak Force / Dynamic or Isometric Peak Force

Example:

Using the data from Table 1.

Dynamic Strength Index (DSI) = CMJ peak force (N) / IMTP peak force (N)

DSI = 1450 / 3178

DSI = 0.46

Is the Dynamic Strength Index valid and reliable?

The DSI has been proven to be both a valid and reliable measure of maximal and explosive strength capacity in recreational (6), university (5), and elite athletes (25). Furthermore, the following combination of exercises have been proven to be reliable when measuring DSI:

- CMJ and IMTP (3)

- Static SJ and IMTP (5, 6)

- Ballistic Bench Throw and Isometric Bench Press (26)

It has also been verified as a sensitive and useful tool to evaluate and monitor performance changes over the course of a training programme (26).

How should the Dynamic Strength Index guide your training program?

Once the athlete’s DSI has been calculated, the strength and conditioning coach needs to know what that score tells them, and therefore how to design the training programme based on that score. Table 2 provides some simple examples of various DSI scores.

| Exercise | CMJ Peak Force (N) | IMTP Peak Force (N) | DSI |

| Athlete A | 1,450 | 3,178 | 0.46 (46%) |

| Athlete B | 2,500 | 3,000 | 0.83 (83%) |

| Athlete C | 2,600 | 2,600 | 1 (100%) |

The DSI reflects the percentage of maximal strength “potential” which is not being used within a given motor task (e.g. jump) (27). In other words, it demonstrates the athlete’s ability to use their full “force potential” during a ballistic exercise such as a CMJ. So theoretically speaking, if an athlete can express a DSI score of 1 (i.e. Athlete C in Table 2), they are capable of using their full “force potential’. This means the higher the athlete’s DSI, the more capable they are at utilising their “force potential” during a ballistic exercise.

In contrast, the lower the athlete’s DSI, the less capable they are at utilising their “force potential” during a ballistic exercise. A higher DSI means more time should be spent on developing maximal strength (i.e. force production). A smaller DSI means more time should be spent developing RFD using ballistic strength training methods (Table 3) (6).

| Score | DSI Score | Training Emphasis Recommendation |

| Low | <0.60 | Ballistic Strength Training |

| Moderate | 0.60-0.80 | Concurrent Training |

| High | >0.80 | Maximal Strength Training |

- Secomb JL, Farley ORL, Lundgren L Tran TT, King A, Nimphius S, Sheppard JM. Associations between the Performance of Scoring Manoeuvres and Lower-Body Strength and Power in Elite Surfers. International journal of Sports Science & Coaching October 2015 vol. 10 no. 5 911-918 [Link]

- Turner, A. (2009). Training For Power: Principles And Practice. UKSCA, 14, 20-32. [Link]

- Weiss LW, Fry AC, Relyea GE. Explosive strength deficit as a predictor of vertical jumping performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2002 Feb;16(1):83-6. [PubMed]

- ZATSIORSKY, V. Science and Practice of Strength Training. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1995. pp. 34–35. [Link]

- Thomas C, Jones PA, Comfort P. Reliability of the Dynamic Strength Index in collegiate athletes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2015 Jul;10(5):542-5. [PubMed]

- Sheppard, J.M. and Chapman, D.W., An Evaluation of a Strength Qualities Assessment for the Lower Body, Journal of Australian Strength and Conditioning, 2011, 19, 14-20. [Link]

- Kawamori, N, Rossi, SJ, Justice, BD, Haff, EE, Pistilli, EE, O’Bryant, HS, Stone, MH, and Haff, GG. Peak force and rate of force development during isometric and dynamic mid-thigh clean pulls performed at various intensities. J Strength Cond Res 20: 483–491, 2006. [PubMed]

- Suchomel TJ, Nimphius S, Stone MH. The Importance of Muscular Strength in Athletic Performance, Sports Med. 2016 Feb 2. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed]

- Asci, A, and Acikada, C. Power production among different sports with similar maximum strength. J. Strength Cond. Res. 21: 10 – 16, 2007. [PubMed]

- Baker, D. The effects of an in-season of concurrent training on the maintenance of maximal strength and power in professional and collegeaged rugby league football players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 15: 172-177, 2001. [PubMed]

- Baker, D, and Newton, RU. Observation of 4-year adaptations in lower body maximal strength and power output in professional rugby league players. J. Aust. Strength Cond. 18: 3-10, 2008. [Link]

- Nuzzo, JL, McBride, JM, Cormi P, and McCaulley, GO. Relationship between countermovement jump performance and multijoint isometric and dynamic tests of strength. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 23: 699-707, 2008. [PubMed]

- Peterson, MD, Alvar, BA, and Rhea, MR. The contribution of maximal force production to explosive movement among young collegiate athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 20(4): 867–873. 2006. [PubMed]

- Baker, D. A series of studies on the training of high intensity muscle power in rugby league football players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 15: 198-209, 2001. [PubMed]

- Baker, D, Nance, S, and Moore, M. The load that maximises the average mechanical power output during explosive bench press throws in highly trained athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 15: 20-24, 2001. [PubMed]

- Baker, D, Nance, S, and Moore, M. The load that maximises the average mechanical power output during jump squats in power-trained athletes J. Strength Cond. Res. 15: 92-97, 2001. [PubMed]

- Baker, D, and Newton, RU. Adaptations in upper body maximal strength and power output resulting from long-term resistance training in experienced strength-power athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 20: 541-546, 2006. [PubMed]

- Schmidtbleicher, D. Training for power events. In: Strength and Power in Sport. P.V. Komi, ed. London: Blackwell Scientific, 381–395, 1992.

- Stone, MH, O’Bryant, HS, McCoy, L, Coglianese, R, Lehkkuhl, M, and Shilling, B. Power and maximum strength relationships during performance of dynamic and static weighted jumps. J. Strength Cond. Res. 17: 140 – 147, 2003. [PubMed]

- Stone, MH, Sanborn, K, O’Bryant, HS, Hartman, M, Stone, ME, Proulx, C, Ward, B, and Hruby, J. Maximum strengthpower performance relationships in collegiate throwers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 17: 739-745, 2003. [PubMed]

- McLellan, CP, Lovell, DI, and Gass, GC. The role of rate of force development on vertical jump performance. J Strength Cond Res 25(2): 379–385, 2011. [PubMed]

- Miura, K, Yamamoto, M, Tamaki, H, and Zushi, K. Determinants of the abilities to jump higher and shorten the contact time in a running 1-legged vertical jump in basketball. J Strength Cond Res 24(1): 201–206, 2010. [PubMed]

- Taylor, M. J. D., & Beneke, R. (2012). Spring Mass Characteristics of the Fastest Men on Earth. International journal of sports medicine, 33(8), 667. [Link]

- Stefanyshyn, D. & Nigg, B. (1998) Contribution of the lower extremity joints to mechanical energy in running vertical jumps and running long jumps. Journal of Sport Sciences, 16, 177-186. [PubMed]

- Young KP, Haff GG, Newton RU, Sheppard JM. Reliability of a novel testing protocol to assess upper-body strength qualities in elite athletes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2014 Sep;9(5):871-5. [PubMed]

- Young KP, Haff GG, Newton RU, Gabbett TJ, Sheppard JM. Assessment and monitoring of ballistic and maximal upper-body strength qualities in athletes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2015 Mar;10(2):232-7. [PubMed]

- Siff, MC. Supertraining. Denver, Colorado: Supertraining Institute. 9 – 21, 2003. [Link]