Contents of Article

- Summary

- What is the isometric mid-thigh pull (IMTP)?

- Why is the IMTP important?

- How do you perform the IMTP test?

- How to collect IMTP data?

- Are there any issues with the IMTP?

- Is future research needed with the IMTP?

- Conclusion

- References

- About the Author

Summary

The isometric mid-thigh pull (IMTP) test is an effective and reliable way to test maximal strength in youth and adult athletes. Research has shown that performance variables from the IMTP test correlate to athletic movements such as the vertical jump and sprint speed.

Administering the IMTP test is a safer and more time-efficient method than traditional 1RM testing which also benefits athletes with a low training age. The IMTP and use of isometrics can be used in a training programme to effectively develop strength, power, and tendon stiffness.

When administering the IMTP test, the protocol needs to be standardised to ensure the most reliable data possible.

What is the isometric mid-thigh pull (IMTP)?

The isometric mid-thigh pull (IMTP) test is a multi-joint exercise designed to assess the strength and force production capabilities of an athlete’s entire body. As stated in the name, the exercise is isometric in nature, meaning the bar is fixed in place and does not move.

A maximal isometric action allows individuals to produce a greater force than a maximal concentric action. For this reason, IMTP is often used to measure maximum strength [1, 2] in both research and by strength and conditioning coaches. The IMTP requires an individual to pull on a fixed barbell with a maximal effort for 3-5 seconds. When performed on top of a force plate, the test can quantify peak force, relative force, rate of force development (RFD), time to peak force, etc.

Why is the IMTP important?

The IMTP assesses performance qualities that are critical to most sporting actions such as strength and power. Research has found a correlation between maximum strength and sprint speed [3, 4], along with the rate of force development and vertical jump performance [5, 6]. Data retrieved from the IMTP can be combined with other tests that give coaches valuable information such as the Dynamic Strength Index. Khamoui et al. [5] investigated dynamic strength and concluded that explosive isometric force production within the first 100 milliseconds correlated with vertical jump height. This suggests that isometric capabilities have velocity and time characteristics transferable to sporting actions.

The IMTP is a safer and more time-efficient alternative to one-repetition maximum (1RM) testing. Performing the IMTP requires a low training age and is safe to perform since the test does not put individuals in compromising body positions. S&C coaches who have athletes with a low training age may not feel comfortable with their athletes testing with heavy loads. Performing a 1RM test may cause individuals to break technique, this can be counter-productive for coaches who are still installing good movement patterns in their athletes.

The test is also time-efficient since performing the IMTP lasts only 3-5 seconds. Building up to a 1RM can take upwards of half an hour for a single athlete, whereas the IMTP allows coaches to assess multiple athletes within a short period of time.

Little research exists on the IMTP test within younger populations, however, the test can be administered to both youth [1] and adult athletes [7]. Moeskops et al. (2018) [8] established that the IMTP test is reliable in measuring peak force in pre- and post-peak height velocity youth athletes. With youth sports becoming more competitive, being able to quantify strength in young athletes can give a performance and injury-risk advantage. For this reason, youth athletes should also train maximal strength.

Brownlee et al. (2018) [1] used the IMTP test to assess differences in strength during the season with youth football athletes who regularly participate in strength training. No changes in maximum force were found, indicating the training received did not make the athletes stronger, possibly due to not being exposed to a great enough intensity. For this reason, the IMTP can be used as both a training method for maximal strength in youth athletes and as an in-season monitoring tool.

Another benefit of the IMTP is that it mirrors the positioning of the second pull in the clean & jerk weightlifting movement, which many consider to be where the most power is developed in the lift. Olympic weightlifting is undoubtedly an effective way to increase power production in athletes [9]. The IMTP also has viability as a training exercise in the weight room.

Isometric training has gained popularity with many S&C coaches for multiple reasons. For one, isometrics can be performed at multiple angles and train ‘weak points’ in athletes by allowing them to produce as much force as possible in a range of motion they are unable to. Anecdotally, this has helped many powerlifters and may also benefit dynamic sport athletes.

Secondly, isometric training provides variability to athletes performing conventional concentric and eccentric training. Isometrics can also provide a greater intensity to training without the fatigue brought on by loaded repetitions. Finally, isometric training can increase tendon stiffness within the lower limbs when performed regularly [10].

Video 1 – Demonstration of the IMTP test by Innervations

How do you perform the IMTP test?

The IMTP requires individuals to pull on the bar with maximum effort for a continuous 3-5 seconds. Administration of the IMTP test requires a standardised protocol to get the most reliable data.

Required equipment

- Force plate that can record at 1000 Hertz (Hz)

- A barbell that can be adjusted to different heights, including a way to secure the barbell to disallow movement.

- Performance recording sheet

The individual being tested should be sufficiently warmed up and be familiarised with the protocol. Body positioning is critical during the IMTP and can affect the outcome/data produced. Dos’Santos et al. (2017) [11] reported that hip angle significantly affects peak force and RFD, with a hip angle of 145° recommended as optimal. Two practice trials of the IMTP before recording will help prevent intra-individual errors.

The barbell must be placed at the height of an individual’s mid-thighs when they are in a slight Romanian deadlift (RDL) position. Secondly, the athletes should be educated on your cues as well as the signal for when to start the pull. Cueing is important and can help produce the best results from your athletes. Test administrator cues should be concise, sharp, and consistent whilst avoiding over-explanation. Here’s an example of the cues I give when administering the test:

- Step onto the force plate with thighs touching the bar.

- Wrap your hands around the bar without pulling.

- Shoulders back. Chest up. Look straight ahead.

- 3, 2, 1, PULL!

Testers should be experienced with the software being used to calculate the IMTP. A minimum baseline of 1-2 seconds is usually required in most software before the start of a pull. During this time the athlete should be standing completely still before the start of their pull. This allows time-dependent variables such as RFD and time-to-peak force (TPF) to be measured accurately. Let athletes rest between 1-2 minutes between trials.

In the video below I show you how you can use a £35 crane scale to measure IMTP and also collect the data using our free IMTP scoring spreadsheet.

How to collect IMTP data?

If you’d like to start testing your athletes’ strength and power using the IMTP, then you’ll need a spreadsheet which helps you collect and analyse all of the data. Luckily for you, we created a simple and easy-to-use IMTP scoring spreadsheet which allows you to do just that. You can download our free IMTP scoring spreadsheet via the box below.

Are there any issues with the IMTP?

The main concern with the IMTP is the equipment needed to perform the test. Most coaches do not have access to a force plate which allows them to measure peak force and RFD. Similarly, the setup required for the IMTP can take some time depending on the equipment on hand or the limitations of a gym.

Recently, RFD in the IMTP test has been shown to correlate with sprint acceleration [12]. However, the IMTP measures the ability to produce force primarily in the vertical direction. The variables taken from the IMTP may have a limited transfer to horizontal, frontal, and transverse plane movements. While performance was carried across a different force vector in the Townsend [12] study, isometrics in a more specific direction may be more valid since most sports are played in multiple vectors.

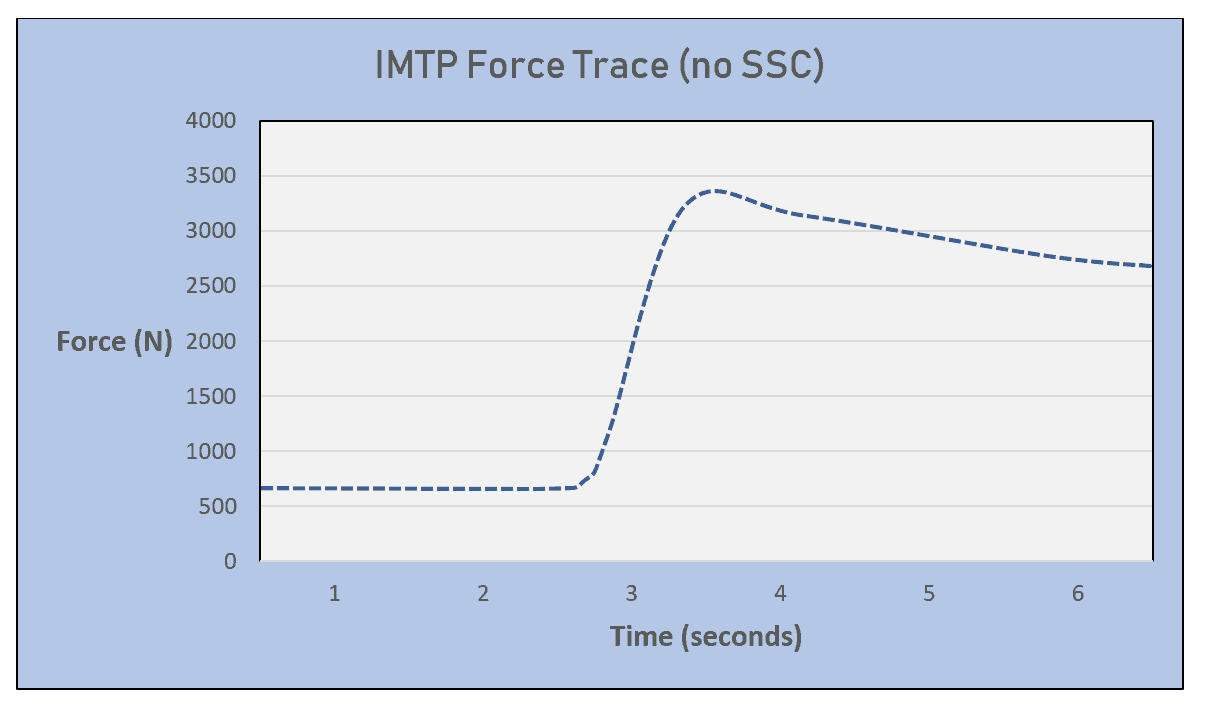

During an IMTP test, a countermovement action may be present on a force trace between the end of a baseline and the onset of the pull (Figure 1). This affects the reliability of the IMTP variables because it means the individual used the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) to their advantage to produce more force. While the SSC is evident in athletic movements, this movement during testing can vary greatly which inherently makes the testing variables less reliable.

Familiarisation is needed with all participants performing the IMTP for the first time. Moeskops et al. (2018) [8] reported that pre-peak height velocity athletes require multiple familiarisation trials before producing reliable peak force, RFD, and time-to-peak force. Older athletes unfamiliar with body positioning and with a low training age may also need multiple familiarisation trials.

Is future research needed with the IMTP?

A plethora of research on the IMTP already exists. Some interesting areas and directions into this research topic include:

- Using the single-leg isometric mid-thigh pull to assess lower-limb asymmetries.

- A horizontal isometric pull/push test.

- Acute effects of short-term isometric-only training on vertical jump performance.

Conclusion

The IMTP is a reliable and valid test for measuring maximum strength in both youth and adult athletes. In research, the test provides sports scientists with critical information such as peak force and RFD. For coaches, the use of the IMTP and isometric training may increase strength and power development without fatiguing muscles. Coaches may use this as an alternative to 1RM testing because it is both safe and time-efficient. Also, the IMTP can be used to assess/monitor maximum strength during the in-season.

When administering the IMTP, testers should be confident in their protocol and standardise their methods to avoid error and reliability issues.

- Brownlee TE, Murtagh CF, Naughton RJ, Whitworth-Turner CM, O’Boyle A, Morgans R, Morton JP, Erskine RB, and Drust B. (2018). Isometric maximal voluntary force evaluated using an isometric mid-thigh pull differentiates English Premier League youth soccer players from a maturity-matched control group. Science and Medicine in Football . https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/24733938.2018.1432886

- De Witt JK, English KL, Crowell JB, Kalogera KL, Guilliams ME, Nieschwitz BE, Hanson AM, and Ploutz-Snyder KL. (2018). Isometric midthigh pull reliability and relationship to deadlift one repetition maximum. J Strength Cond Res 32(2): 528-533. https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/Abstract/2018/02000/Isometric_Midthigh_Pull_Reliability_and.28.aspx

- Wang R, Hoffman JR, Tanigawa S, Miramonti AA, La Monica MB, Beyer KS, Church DD, Fukuda DH, and Stout JR. (2016). Isometric mid-thigh pull correlates with strength, sprint, and agility performance in collegiate rugby union players. J Strength Cond Res 30(11): 3051-3056. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26982977

- McBride J, Blow D, Kirby T, Haines T, Dayne A, and Triplett N. (2009). Relationship between maximal squat strength and five, ten, and forty-yard sprint times. J Strength Cond Res 23: 1633-1636. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19675504

- Khamoui AV, Brown LE, Nguyen D, Uribe BP, Coburn JW, Noffal GJ, and Tran T. (2011). Relationship between force-time and velocity-time characteristics of dynamic and isometric muscle actions. J Strength Cond Res 25(1): 198-204. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19966585

- Wisloff U, Castagna C, Helgerud J, Jones R, and Hoff J. (2004). Strong correlation of maximal squat strength with sprint performance and vertical jump height in elite soccer players. British Journal of Sports Medicine 38: 285- 288. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1724821/

- Beckham GK, Sato K, Santana HAP, Mizuguchi S, Haff GG, and Stone MH. (2018). Effect of body position on force production during the isometric midthigh pull. J Strength Cond Res 32(1): 48-56. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28486331

- Moeskops S, Oliver JL, Read PJ, Cronin JB, Myer GD, Haff GG, and Lloyd RS. (2018). Within- and between- session reliability of the isometric mid-thigh pull in young female athletes. J Strength Cond Res (ahead of print). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29547490

- Hoffman JR, Cooper J, Wendell M, Kang J. (2004). Comparison of Olympic vs. Traditional power lifting programs in football players. Strength Cond Res 18(1):129-135. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14971971

- Kubo K, Kanehisa H, Fukunaga T. (2001). Effects of different duration isometric contractions on tendon elasticity in human quadriceps muscles. J Physiol 536(2): 649-655. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2278867/

- Dos’Santos T, Thomas C, Jones PA, McMahon JJ, and Comfort P. (2017). The effect of hip joint angle on isometric midthigh pull kinetics. J Strength Cond Res 31(10): 2748-2757. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28933711

Townsend JR, Bender D, Vantrease W, Hudy J, Huet K, Williamson C, Bechke E, Serafini P, Mangine GT. (2018). Isometric mid-thigh pull performance is associated with athletic performance and sprinting kinetics in division 1 men and women’s basketball players. J Strength Cond Res (ahead of print). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/28777249/