Contents

- Introduction

- What are the Technical Aspects of Agility?

- What are the Cognitive Aspects of Agility?

- Do Elite Athletes Possess better Agility than Sub-Elite Athletes?

- Number 1 – Strength & Power Training

- Number 2 – Extensive Closed Chain Agility

- Number 3 – Extensive Open Chain Agility

- Number 4 – Intensive Agility

- Number 5 – Small Sided Games

- Conclusion

- About the Author

- Comments

Introduction

The purpose of this article is to explore the development of agility in invasion sports (e.g. rugby, football or basketball). However, some of these principles are transferable to other sports such as racquet sports. Invasion sports can be defined as opposing teams attempting to invade their opponent’s territory with an attack to enhance scoring opportunities (13); attacking, meaning there is a forward progression to score and defending meaning protecting goals and trying to win possession (13). So, what is agility and how do we develop it? Is it the endless obstacle courses you see on Instagram? Agility is reactive in nature. Hence why the term ‘reactive’ agility is redundant. If there is no reaction, it’s not agility. Agility is defined as ‘a rapid whole-body movement with change of velocity or direction in response to a stimulus’ (10).

Agility can be defined as an ‘open’ skill due to its reactive nature. However, many athletes train agility as a ‘closed’ skill where change of direction (CoD) is pre-planned around obstacles such as poles, cones, lines and ladders. This ‘closed’ skill is also known as change of direction speed (CoDS). It is important to note that this closed skill rarely occurs in invasion sports and is most notably used in sports such as cricket and baseball (running between wickets or around bases). This is why open-environment sports require a sport-specific stimulus to find transfer when looking to improve agility.

What are the Technical Aspects of Agility?

Agility can be broken down into three components cognitive, physical and technical (11). The ladder or obstacles (cones, poles) are often used to develop the technical aspect of agility, these being feet placement, adjustment of steps to accelerate and decelerate, body lean and posture. It has been shown that pre-planned side steps result in; greater lateral foot placement, greater lateral movement speed, increased hip abduction, and greater forward foot displacement while showing lower knee joint angles and lesser forces through the knee than unplanned side stepping (1, 8, 12).

A study by Wheeler & Sayer (2010) demonstrates and explains the technical differences between pre-planned and unplanned side steps (12). The researchers found significant differences in lateral movement speed and foot position between unplanned and pre-planned side stepping. Pre-planned side-stepping conditions demonstrated greater lateral movement speed and greater forward displacement of the foot compared to unplanned side-stepping. The greater lateral movement speed in the pre-planned side-step indicates that movement was directed towards the intended direction change.

The greater forward displacement of the foot in the pre-planned side-step may have been due to the lack of reactive stimulus. The unpredictable nature of the unplanned side-step may benefit from having the foot closer to the centre of mass making movement in either direction easier. This research demonstrates a decision-making element limits lateral movement speed during a side-step and therefore, creates a technically different movement as foot placement patterns were different between unplanned and pre-planned side steps.

Another study also showed greater lateral foot placement and therefore greater hip abduction (away from the midline of the body) during planned vs unplanned side stepping (8). The authors also noted initial knee adduction (towards the midline of the body) moments during planned side-stepping suggesting during early stance, movement of the centre of mass (CoM) is initiated toward the stance foot. However, during unplanned side-stepping, the knee moment was towards abduction indicating an immediate response to redirect the CoM away from the stance foot. Why is this important? According to the authors, these results suggest during the planned side-step, the subjects completed weight acceptance and then executed the turn. In contrast, during the unplanned side-step, the subjects attempted to initiate the turn at initial contact.

CoDS drills do not replicate the technical aspects of agility as each of these technical aspects is preparing for a sharp rapid change in velocity in response to a sport-specific stimulus. We know that pre-planned agility (CoDS) and unplanned agility manoeuvres are independent qualities [3]. Running your feet quickly through a ladder or cones whether it be forwards or laterally, does not provide the same stimulus as preparing and performing a rapid step, the footwork and body posture do not match.

Additionally, when using pre-planned obstacle drills, athletes will often get into awkward body positions to manoeuvre around poles or cones. You only give the athlete one side-stepping option through most pre-planned drills where teaching the athlete a repertoire of side steps can allow them to apply different side-step manoeuvres in different situations.

What are the Cognitive Aspects of Agility?

To make the cognitive component of agility easier to understand, it can be renamed into decision-making speed and accuracy. This can be broken down further into visual scanning, anticipation, pattern recognition and knowledge of situations (13). While these four cognitive attributes are important, they are applied differently when it comes to attacking and defending agility.

Attacking agility involves evasion to maintain possession while defensive agility involves moving to position to pressure the attacker for a turnover or tackle (13). The thought process between the two agility scenarios is quite different. Here are some examples of an attacking player in any invasion sport – which way is he (the defender) moving? Can I fake a pass? Is there space for me to manoeuvre in this direction?

Whereas a defender may be thinking – Where are my or their teammates? Which way will they go? Is this a fake? Again, being able to process this information quickly comes down to the four cognitive attributes of agility. This is why treating agility as an open skill is so important. Attackers react to defenders and defenders react to attackers. There is also further evidence against using closed skilled drills such as obstacles and ladders as a way to train agility. CoDS and agility are independent qualities.

As stated in the review by Young et al. (2015), the correlation between CoDS and agility is only 29 % when averaged out over four studies (13). However, when averaged out over all six studies in this area, the correlation was only 21 %. Since both 21 % and 29 % values are well under 50 % commonality, it indicates CoDS and agility are independent skills. In other words, being quick at changing direction does not necessarily mean you will also be quick in your sporting scenarios when there’s a reactive decision-making component.

Do Elite Athletes Possess Better Agility than Sub-Elite Athletes?

To really assess the importance of this decision-making element of agility in invasion sports, we can compare this attribute between higher and lower standards of players. If the higher-skilled group of players are better at the test, the quality assessed by that test can be said to be more important for performance in that sport (3).

Young and colleagues showed that the higher standard players perform better in an agility test but not in a CODS test (13). In this review, they found that higher-standard players typically produce faster decision-making times compared to lower-standard players in netball and rugby league (5, 6). In a study with Australian Rules football players, professional players were found to be slightly faster and more accurate in their decisions when reacting to an attacker changing direction than elite junior players (2). Similar results were observed in soccer where elite players were faster and more accurate in anticipating the pass direction in a one-on-one situation compared to recreational players (11). Furthermore, higher-standard players are less susceptible to fakes and steps (7,9).

It should be noted that higher-skilled players only perform better when reacting to a sport-specific stimulus. This questions the use of agility devices such as agility lights that flash as a stimulus to react and if these devices are really developing agility. The research presented above supports the argument that agility should be trained with a sports-specific stimulus allowing the athlete to see and solve as many patterns and situations as possible. This should be done for both attacking and defending scenarios. For the athlete to solve attacking agility situations, they will need a toolbox filled with different evasion manoeuvres also known as side steps.

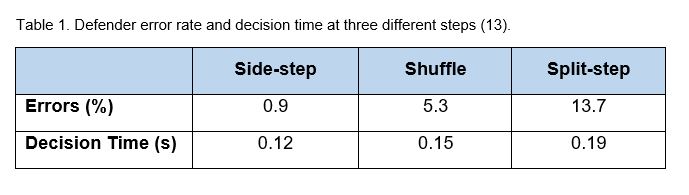

Side steps are not pre-planned during a game scenario. A side-step is chosen by the athlete based on speed coming into the evasion maneuverer, what the opponent and/or other opponents are doing/going to do and the space available. Hence the importance of teaching your athletes a repertoire of steps for them to draw from. The table below shows three different steps and shows the defender’s error rate at correctly picking the right direction and the time it takes for the defender to make a decision. All steps showed a significant (p<0.05) difference between each other.

While the split step seems superior to the other two options, a split step cannot be used when approaching at high velocity so it may be better suited to situations where play has slowed down. In contrast, a side-step is a great option to use at high velocity (e.g. runaway 1 on 1 with the fullback) but may not be as advantageous during slower periods of play.

When it comes to pre-planned agility drills, the athlete can only use the side-step as there is no need to deceive a defender and the athlete is trying to change direction as fast as possible (e.g. ‘L’ run). Most pre-planned drills are done at a high velocity where the focus is CODS. Furthermore, a step involves a head-up, eyes-forward posture where you are reacting to an opponent’s movements based on your own (deceiving or faking).

Number 1 – Strength & Power Training

Once foundational levels of strength and power have been established, developing lateral strength and power will potentially be of benefit to enhancing lateral movement speed. Some examples of lateral strength exercises:

- Cossack Squat

- Lateral Lunge

- Lateral Box Step Up

- Lateral Slide Board Lunge

- Lateral Sled Drag

Some examples of lateral ballistic/plyometric exercises:

- Lateral Skater Hop & Stick Landings

- Repeated Lateral Skater Hops

- Lateral Hop & Stick Landings

- Repeated Lateral Hops

Number 2 – Extensive Closed Chain Agility

The general rule for programming in strength and conditioning is moving from extensive exercise to intensive. The most extensive exercise you can perform in the realm of developing agility skills are closed chain drills. However, this does not mean using CoDS drills. Rather, this time is for you as the coach to teach basic CoD manoeuvres that can be scaled and used in open drill scenarios.

It is important to cover both defensive and offensive agility options. Here are some examples of both:

Offensive Agility – Side-step, shuffle step, split step & swerve run

Defensive Agility – Shuffle, crossover, player tracking & 180° CoD

These can be performed in various extensive circuits with 2-3 rounds to develop specific work capacity and robustness along with drilling the technical movements in a closed environment. For example:

1) Single Shuffle 1 x 20-30 m

2) 180° COD 1 x 1/side (5 m in, 5 m out)

3) 45° Side-step (5 m in, 5 m out)

4) Swerve Run 1 x 20-30 m

Number 3 – Extensive Open Chain Agility

Following extensive closed-chain agility circuits, you can start putting these movements under a little bit of stress by applying an external stimulus to react to and drills with a higher intensity and intent. These should be performed individually with increased rest periods, rather than a circuit-like fashion. Some examples are:

- Shuffle Mirror Drill

- Side-step Mirror Follow Drill

- Gauntlet Swerve Runs

Number 4 – Intensive Agility

Evasion drills can be done in a variety of different ways such as 1v1 or 2v1 drills. It is important these drills are performed in a small marked-out area so attackers can’t just run around the defender, especially when you want to emphasize CoD manoeuvres. The aim is for the attacker(s) to evade the defender by trying to deceive the defender.

In doing so, applying the evasion manoeuvre the attacker feels is most appropriate based on the defender’s movements. The defender reacts to the attacker to stop the attacker from progressing or depending on the sport, tackling or trying to attain possession of the ball. This provides the sport-specific stimulus to both attackers and defenders and allows the athletes to solve the situations themselves. This way both athletes get a chance to attack and defend allowing them to develop both attacking and defending agility qualities.

An important tip for these drills is to vary the angle the attackers and defenders come into the drill (13). For example, attackers and defenders might start head-on, whereas the next repetition they may start with the defender coming in from the side or both attackers and defenders starting on opposite corners. This will provide a greater overall agility stimulus as you can cover more than one pattern or situation.

1v1 Rugby evasion drill

1v1 Football evade & score

Number 5 – Small Sided Games

Small Sided Games (SSG) are another great way to develop agility as they potentially develop various fitness components, skills, tactics and game awareness (4). To give SSGs an agility focus, some general guidelines need to be considered. A study by Davies et al. (2013) investigated the effect of playing area size, number of players per side and rule changes on total agility efforts (4). The researchers found:

- Reducing player numbers increases the total number of agility manoeuvres compared with a larger number of players (3 a side vs 5 a side).

- The greater the density of the game (more players in a given space), the greater the number of agility manoeuvres.

- Reducing the number of passes allowed before scoring increases the agility demand.

- Having the coach provide encouragement to the athletes during the game can help get the athletes that lack engagement more involved.

Young & Rogers (16) conducted a study with Elite junior Australian Rules Football players (4). Players were split into two groups (SSG group and a CoD direction group). Players completed 11 x 15 min sessions over 7 weeks during the season of either just SSGs or just CoD drills depending on the group they were randomly selected for. Researchers tested the athletes’ pre and post-intervention on a planned Australian Football League agility test for CoDS and a video-based defensive agility test reacting to an attacker.

The CoD group did not improve on the planned agility test. Furthermore, they did not improve their total agility time (total time to complete the defensive agility test) and only slightly improved their agility reaction time (decision time) by 4 %. Similarly, the SSGs group didn’t improve on the planned agility test. However, total agility time improved by 4 % while agility reaction time showed a huge improvement of 31 % post-intervention. The SSGs group’s total agility time improvement was entirely due to the large improvement in reaction time. This is an impressive change from just 11 x 15 min SSGs training sessions over 7 weeks.

Conclusion

- Perform lateral strength/power training to enhance lateral movement speed once foundational strength and power are developed.

- Move from extensive to intensive agility manoeuvres.

- Provide a sport-specific context for your agility drills such as 1v1 evasion drills, not pre-planned cone and ladder drills.

- SSGs are effective methods for enhancing decision-making time and therefore, total agility time.

Agility is more than running through cones and ladders as quickly as possible. Agility involves a perceptual component that is specific to the sport. However, this does not mean that all developmental agility exercises should only involve sport-specific scenarios. Rather, like you would in other areas of your programme, move from extensive to intensive means in order to put the skills taught to athletes gradually under more and more pressure to develop the 3 components of agility, as part of a comprehensive agility program.

- Brown, S. R., Brughelli, M., & Hume, P. A. (2014). Knee mechanics during planned and unplanned sidestepping: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports medicine, 44(11), 1573-1588.

- Carlon, T., Young, W., Berry, J., Burnside, C. Association between Perceptual Agility Skill and Australian Football Performance. Journal of Australian Strength and Conditioning, 2013; 21, 42-44.

- Coh, M., Vodicar, J., Žvan, M., Šimenko, J., Stodolka, J., Rauter, S., & Mackala, K. (2018). Are Change-of-Direction Speed and Reactive Agility Independent Skills Even When Using the Same Movement Pattern?. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 32(7), 1929-1936.

- Davies, M., Young, W., Farrow, D., & Bahnert, A. Comparison of agility demands of small-sided games in elite Australian football. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 2013; 8, 139-147

- Farrow, D., Young, W., Bruce, L. The Development of a Test of Reactive Agility for Netball: A New Methodology, Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 2005; 8, 52-60.

- Gabbet, T., Benton, D. Reactive Agility of Rugby Leagues Players. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 2009; 12, 212-14.

- Henry, G., Dawson, B., Lay, B., Young, W. Effects of a Feint on Reactive Agility Performance. Journal of Sports Sciences, 2012; 30, 787-795.

- Houck, J. R., Duncan, A., & Kenneth, E. (2006). Comparison of frontal plane trunk kinematics and hip and knee moments during anticipated and unanticipated walking and side step cutting tasks. Gait & posture, 24(3), 314-322.

- Jackson, R., Warren, S., Abernethy, B. Anticipation Skill and Susceptibility to Deceptive Movement. Acta Psychologica, 2006; 123, 355-371.

- Sheppard, J. M., & Young, W. B. (2006). Agility literature review: Classifications, training and testing. Journal of sports sciences, 24(9), 919-932.

- Williams, A., Davids, K. Visual Search Strategy, Selective Attention, and Expertise in Soccer. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 1998; 69, 111-128.

- Wheeler, K., Sayers, M. Modification of agility running technique in reaction to a defender in rugby union. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 2010;9,445-451

- Young, W. SPRINZ Conference 2015. Auckland Millennium Institute of Sport.

- Young, W., Dawson, B., Henry, G. Agility and Change of Direction Speed are Independent Skills: Implications for Training for Agility in Invasion Sports. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 2015; 10(1) 159-169

- Young, W., & Farrow D. The importance of a sport-specific stimulus for training agility. Strength and Conditioning Journal. 2013; 35(2), 39-42

- Young, W & Rogers, N. Effects of small-sided game and change-of-direction training on reactive agility and change-of-direction speed. Journal of Sports Sciences, 2004; 32(4), 307-314