Contents of Article

- Summary

- What is a massage?

- Can massage improve recovery?

- What are the physiological effects of massage?

- What are the biomechanical effects of massage?

- What are the neurological effects of massage?

- What are the psychological effects of massage?

- What are the immunological effects of massage?

- Are there any issues with massage?

- Is future research into massage needed?

- Conclusions

- References

- About the Author

Summary

Massage after exercise (i.e. post-exercise massage) has been used for many years as a method to improve recovery in athletes, despite the presence of robust scientific evidence to support its effectiveness. Although there is a lot of published research on massage therapy, only a very small portion of it focuses on the use of massage in athletes.

Given the current evidence, post-exercise massage may be an effective tool to promote recovery, but not for the majority of reasons it is so often believed to be. Acknowledging the popularity of this recovery method, and the substantial lack of evidence, it is highly recommended that more research is conducted to fully understand its uses and limitations.

What is a massage?

Massage is defined as ‘‘mechanical manipulation of body tissues with rhythmical pressure and stroking for the purpose of promoting health and well-being’’ (1), and it is used in sports for many purposes (2, 3). These include:

- Pre-exercise preparation

- Post-exercise recovery

- Injury prevention

- Injury rehabilitation

This article will focus on the efficacy of post-exercise massage as a method of accelerating the recovery process in sports.

The practice of using post-exercise massage to facilitate recovery has been used for many years with scientific research dating back to the early 1970s (4). Over time, this recovery strategy has become a staple in many high-performance sports environments. It has been reported that 78 % of professional football (soccer) players use post-exercise massage as a means of recovery (5). Classical massage, otherwise known as Swedish or Western massage, appears to be the most common form of massage used within sporting settings, and certainly within athletic research (3). This form of massage includes techniques such as:

- Effleurage (sliding/gliding movements)

- Petrissage (tissue kneading or pressing)

- Tapotement (rapid striking)

- Friction (pressure application)

- Vibration (tremulous shaking movements)

Other techniques such as underwater water-jet massage (6), acupressure and connective tissue massage (7) are also somewhat common, however, these will not be discussed within the scope of this article.

Can massage improve recovery?

It seems to be a common belief that massage can positively enhance recovery, and there are many reasons people believe this to be true. Some of the most common reasons massage is thought to enhance recovery are (8, 3):

- Relieving muscle tension

- Reducing muscle pain

- Reducing muscle spasms and swelling

- Increasing local blood flow

- Promoting the delivery of oxygen and nutrients

- Increasing flexibility and range of motion

- Enhancing clearance of substances such as blood lactate or creatine kinase

However, there is little evidence to support some of these claims. In fact, there are many additional reasons that post-exercise massage may be beneficial which are not listed above. This article will, therefore, discuss the current body of research, and attempt to identify the mechanisms responsible for the enhanced recovery.

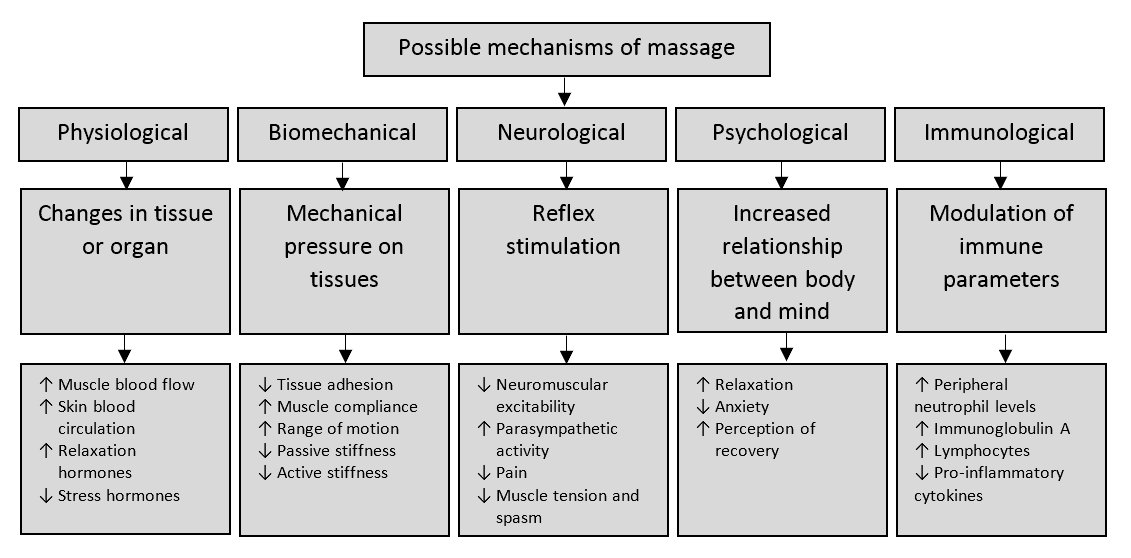

Various mechanisms thought to be responsible for massage’s ability to facilitate recovery have been researched; which include:

- Physiological

- Biomechanical

- Neurological

- Psychological

- Immunological

With these in mind, this article will now dissect each mechanism in order to provide a degree of clarity to this form of recovery. Figure 1 displays a theoretical model of the mechanisms currently thought to be responsible for the enhancement of post-exercise recovery.

What are the physiological effects of massage?

Increased Skin and Muscle Temperature

The repeated and continual rubbing of the skin causes friction, resulting in increased skin temperature (9) and a proposed increase in blood flow, otherwise known as hyperaemia. There is supporting evidence that effleurage can increase skin and intramuscular temperature as deep as 2.5cm, but muscle temperatures deeper than 2.5cm were not affected (10). Another study also reported that effleurage resulted in an increase in skin temperature, but this quickly returned to baseline after just 10 minutes (9). This suggests that massage, particularly effleurage, may have very little effect on intramuscular temperatures.

Increased Blood Flow

Various studies have been conducted on the effects of massage on localised blood flow and shown positive effects (increased blood flow) (4, 11-14), however, these studies severely lack authority due to their poor quality – that being, small sample sizes (11, 14, 4) and no reported statistical analysis (11 -14, 4). Other, more robust, studies have found no increase in blood flow following a massage intervention (15, 16). However, they did not measure microcirculation in the muscle which may have been affected. Another study even showed that post-exercise impaired muscle blood flow (17). All this indicates that massage may have little effect on localised blood flow to the muscle, and has not been explored in enough detail.

Aside from its influences on blood flow, one recent study has shown that post-exercise massage may be capable of improving blood vessel function after exercise (18), but this yet again warrants the need for more research.

Blood Lactate Removal

Blood lactate is often used as a measure of fatigue and recovery (19-22). Numerous studies have investigated the effects of massage on blood lactate removal (19, 21-24), with only two reporting any sign of increased removal (20, 24). Contrary, another study found that massage actually impairs the removal of lactic acid from within the muscle after exercise (18). The little quantity of supporting evidence, therefore, questions the ability of massage to promote blood lactate removal.

Hormonal Response

Massage therapy has been shown to cause changes in hormonal levels (cortisol and serotonin) in dance students (25), patients with low back pain (26), depressed adolescent mothers (27), and HIV-positive patients (28). Following the massage intervention, the dancers reported a reduction in anxiety (nervousness) and improved mood (25). Despite some research showing reductions in cortisol levels after massage treatment, a 2011 meta-analysis concluded that massage has no effect on cortisol concentrations (29). Whilst the mechanisms responsible for some hormonal changes (i.e. serotonin) are still unclear, a decrease in pre-competition nervousness/anxiety may be beneficial for sports performance (30).

What are the biomechanical effects of massage?

Passive Stiffness

Massage is often referred to as “soft-tissue mobilisation”, though there is little evidence to support its ability to reduce soft-tissue stiffness (31, 32). Having said that, three reports have shown decreases in passive muscle stiffness immediately following a massage (32-34), but this increase in tissue mobilisation returned to baseline after 24 hours (32). On the other hand, two studies have reported that massage had no effect on passive stiffness (31, 35). As a result, there is a lack of evidence to determine whether massage is an effective tool for decreasing passive muscle stiffness.

Active Stiffness

To the author’s knowledge, no studies to date have examined the effects of massage on active stiffness.

Joint Range of Motion

Static flexibility is often defined as “the range of motion available to a joint or series of joints” (36). Multiple studies have shown that classical massage is capable of increasing the joint range of motion (25, 37-39). However, it is very important to note that these studies are not particularly robust, and thus further investigation is encouraged (30).

What are the neurological effects of massage?

Parasympathetic Activity

The evidence supporting massage and other forms of soft-tissue therapy (e.g. myofascial trigger point therapy) and their ability to influence parasympathetic modulation appears to be mounting (9, 40-53). In other words, massage has been shown to increase parasympathetic activity leading to a reduction in blood pressure (48, 54, 55), heart rate (48), and an increase in heart rate variability (46, 49, 50, 51, 53).

An increase in parasympathetic activity simply relates to a heightened state of relaxation, often referred to as a “rest and digest” state. Whilst there is a substantial body of evidence supporting the use of massage to increase parasympathetic modulation, most of this research has been conducted in nursing and therefore outside of the athletic environment.

Neuromuscular Excitability and the H-Reflex

Neuromuscular excitability is measured by assessing changes in the Hoffman reflex (H-reflex) amplitude (30). In fact, this is the same technique used to measure any potentiation effects when attempting to induce post-activation potentiation (56, 57). Massage has been shown to reduce neuromuscular excitability (i.e. the H-reflex), and it is thought to do so by stimulating the sensory receptors and reducing muscle tension (58-61). Having said that, the cutaneous mechanoreceptors were not responsible for the changes in H-reflex amplitude in the calf muscle (60).

As a result, the inhibitory effects of massage may originate from either the muscle or deep tissue mechanoreceptors (30). This is supported by one study which found a greater reduction in H-reflex response with an increasing depth of massage (62). Put simply, massage depth may be an important factor in reducing neuromuscular excitability.

If massage is capable of reducing neuromuscular excitability, then this might be a reason why massage appears to be a useful tool for reducing muscle tension and spasm (cramping) after exercise. However, this is still a matter of speculation and more research is required to understand the relationship between neuromuscular excitability and massage.

Effects on Pain

Massage is commonly used to treat perceptions of pain following exercise (63, 25, 26, 64-66), and there appears to be a substantial body of evidence which supports massage’s effectiveness in reducing pain in various populations. For example, massage has been shown to reduce the perception of pain in the following:

- Endurance athletes (67, 68)

- Patients with metastatic bone pain (when cancer cells spread into bone tissue) (69)

- Patients with recurrent headaches (70)

- Post-operative pain (71-81)

- Back and leg pain in pregnant women (82)

- Children and adolescents with chronic pain (83)

- Children with cancer and “growing pains” (84, 85)

- Myalgia (pain in a muscle or group of muscles) (86-88)

- Adult cancer patients (89, 90)

- Patients with Carpel Tunnel Syndrome (91)

- Patients with lower back pain (92-97)

- Patients with distal radial trauma and those receiving needle insertions (98, 99)

Though massage has been repeatedly shown to reduce the perception of pain in a variety of populations, there are numerous methodological issues with many of these studies due to the complexity of pain science. To provide a little more detail, pain is not a ‘sensation’, but instead, a ‘perception’ manifested and regulated by a complex neuromatrix. However, the concept of pain is beyond the scope of this article.

Physiological (biochemical substances)

Neurotransmitter substances such as serotonin have been shown to reduce the symptoms of pain (100, 101). Massage has been shown to not only increase the levels of serotonin (102, 25) but also increase dopamine levels – a stress-relieving hormone (102). Thus, massage may be an effective tool for relieving pain by increasing both serotonin and dopamine – but to accept this as concrete evidence would be a matter of assumption.

There is a significant amount of research that repeatedly supports the effectiveness of massage for reducing the perception of pain, though the effects appear to be small (30, 63, 103-107), and the mechanisms are uncertain.

What are the psychological effects of massage?

Anxiety

Among a long list of others, various forms of massage have been shown to reduce anxiety in the following:

- Dancers (25)

- Patients with chronic pain (86)

- Children with illnesses (84, 108)

- Nurses (109, 110)

- Patients with lower back pain (111-113)

- Headaches (114-116)

- Healthy adults (117)

- Patients with generalised anxiety disorder (118)

- Stroke patients (119)

- Elderly (119, 120)

- Adults with hand pain (121)

- Patients with fibromyalgia (120)

Though many studies have shown that massage may be an effective tool for reducing anxiety, it is important to understand that these effects may only last for a short period of time (122). To the best of our knowledge, there is no substantial evidence to suggest that the effects of massage on anxiety are long-lived. Having said this, a reduction in pre-competition anxiety may have positive effects upon sporting performance.

Relaxation

The effects of massage on relaxation have often been measured using the Profile of Mood States questionnaire (POMS). Whilst the POMS questionnaire is a valid and reliable test, it is questionable as a method of measuring relaxation because it technically measures the following six sub-scales: tension, depression, anger, vigour, fatigue and confusion (123).

As a result, a more appropriate method of measuring both short- and long-term states of relaxation is needed. Despite this, recall previously that massage appears to be a potent tool for increasing parasympathetic activity, and this may provide a degree of support for massage to increase relaxation.

Perception of Recovery

Multiple studies have found that participants reported an increase in the perception of recovery after a massage when it was administered both during and after training (23, 124). Though an increased perception of recovery was reported, no physiological markers such as blood lactate and heart rate showed any sign of improvement.

Additionally, the perception of recovery was measured using the Perception Recovery scale which appears to be a useful and practical questionnaire, however, no research has attempted to correlate scores on the test with other markers of recovery (e.g. increased microcirculation, blood lactate removal and creatine kinase concentrations), so its validity is uncertain.

What are the immunological effects of massage?

Peripheral Neutrophil Levels

Post-exercise massage has been shown to modulate immune parameters (e.g. peripheral neutrophil levels) up to 24 hours after the massage (125). It is thought that this may be due to the relocating of the neutrophils from the treated area (126). In contrast, another study concluded that peripheral neutrophil concentrations may not be maintained two hours after the cessation of exercise and massage treatment (127). The little evidence on this topic means it would be senseless to assume that post-exercise massage can influence peripheral neutrophil concentrations.

Immunoglobulin A

Significant recovery of immunoglobulin A (IgA) has been reported after the administration of a post-exercise massage, with greater recovery in females than in males (128). In support of this, increases in IgA concentrations have also been reported post-massage in the elderly population (42).

Lymphocytes

Whilst two studies have observed small increases in certain lymphocyte concentrations (129-130), others have shown no change in other immunological cells whatsoever (B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes, NK cells, and monocytes) (131).

In conclusion, the function of the immune system is far more complex than simply measuring a few immune parameters, and given that there is so much disparity within the research, at this point, it is unclear whether massage can modulate immune parameters. This statement is supported by a 2015 systematic review on the immunological effects of massage after exercise (126).

Are there any issues with massage?

At present, there are a few main concerns regarding the justification and use of massage. Massage therapy is often promoted for reasons that may not be true. For example, many practitioners advertise its ability to promote healing, well-being, and recovery both physiologically and psychologically. The issue with such claims is the lack of scientific evidence to support them. It is especially important to soften our language with certain vulnerable populations (e.g. cancer patients or individuals with HIV) who may be looking for an “immune boost”, or a cure, from alternative and complementary medicines such as massage (132).

Is future research into massage needed?

Given the tremendous lack of research on athletic performance, the use of massage therapy in a sporting context could benefit from additional research in these areas:

- Effects of post-exercise massage on physiological markers (e.g. microcirculation, blood lactate concentrations).

- Effects of post-exercise massage on biomechanical markers (e.g. active and passive stiffness, joint range of motion)

- Effects of post-exercise massage on neurological markers (e.g. neuromuscular excitability, parasympathetic activity, pain)

- Effects of post-exercise massage on psychological markers (e.g. perceptions of recovery, relaxation, anxiety)

- Effects of post-exercise massage on immunological parameters (e.g. IgA, neutrophil and lymphocyte concentrations).

- Optimal massage duration for influencing recovery

- The optimal post-exercise interval before the onset of massage

- Comparison of techniques for influencing recovery

Conclusions

- There are many false accusations with regard to the application of massage which are not supported by scientific evidence.

- Massage may improve skin and muscle temperature, localised blood flow, and the release of serotonin, though these effects may be small and short-lived. On the other hand, massage may not affect blood lactate removal or reduce cortisol concentrations.

- Massage may reduce passive muscle stiffness and increase joint range of motion. Though there is no evidence regarding its effects on active muscle stiffness.

- Massage may increase parasympathetic modulation and decrease neuromuscular excitability.

- Massage may reduce the perceptions of pain by promoting serotonin and dopamine concentrations, but realistically its effects on pain are far from understood.

- Massage may reduce anxiety and increase the state of relaxation, potentially due to its influence on parasympathetic activity.

- Massage may have little, to no, effect on peripheral neutrophil concentrations. However, it may affect immunoglobulin A and lymphocyte concentrations, but the amount of evidence is scarce.

- Most research on massage is conducted within nursing, with very little performed in athletic populations.

- The current scarcity of research on the effects of post-exercise massage on recovery means regulations on accusations should be enforced/tightened until further knowledge is obtained.

- The effects of post-exercise massage on recovery are still substantially unknown.

- Cafarelli E, Flint F. The role of massage in preparation for and recovery from exercise. An overview. SportsMed. 1992;14(1):1–9. [PubMed]

- Moraska A. Sports massage. A comprehensive review. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2005;45(3):370–80. [PubMed]

- Poppendieck W, Wegmann M, Ferrauti A, Kellmann M, Pfeiffer M, Meyer T. Massage and Performance Recovery: A Meta-Analytical Review. Sports Med (2016) 46:183–204. [PubMed]

- Hovind, H., and S.L. Nielsen. Effect of massage on blood flow in skeletal muscle. Scand. J. Rehab. Med. 6:74– 77. 1974. [PubMed]

- Nédélec, M., McCall, A., Carling, C. Legall F, Berthoin S, Dupont G. Recovery in Soccer Part II—Recovery Strategies. Sports Med (2012) 42: 997. [PubMed]

- Viitasalo JT, Niemela K, Kaappola R, et al. Warm underwater water-jet massage improves recovery from intense physical exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1995;71(5):431–8. [PubMed]

- Goats GC, Keir KA. Connective tissue massage. Br J Sports Med. 1991;25(3):131–3. [PubMed]

- Best TM, Hunter R, Wilcox A, et al. Effectiveness of sports massage for recovery of skeletal muscle from strenuous exercise. Clin J Sport Med. 2008;18(5):446–60. [PubMed]

- Longworth J. Psychophysiological effects of slow stroke back massage in normotensive females. Adv Nurs Sci 1982; 4:44-61. [PubMed]

- Drust B, Atkinson G, Gregson W, et al. The effects of massage on intra muscular temperature in the vastus lateralis in humans. Int J Sports Med 2003; 24 (6): 395-9. [PubMed]

- Bell A. Massage and physiotherapist. Physiotherapy 1964; 50: 406-8. [PubMed]

- Dubrosky V. Changes in muscle and venous blood flow after massage. Soviet Sports Rev 1982; 4: 56-7.

- Dubrosky V. The effect of massage on athletes’ cardiorespiratory systems. Soviet Sports Rev 1983; 5: 48-9.

- Hansen T, Kristensen J. Effect of massage, shortwave diathermy and ultrasound upon 133Xe disappearance rate from muscle and subcutaneous tissue in the human calf. Scand J Med Sci Sports 1973; 5: 179-82. [PubMed]

- Tiidus P, Shoemaker J. Effleurage massage, muscle blood flow and long term post-exercise recovery. Int J Sports Med 1995; 16 (7): 478-83. [PubMed]

- Shoemaker J, Tiidus P, Mader R. Failure of manual massage to alter limb blood flow: measures by Doppler ultrasound. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1997; 29 (5): 610-4. [PubMed]

- Wiltshire EV, Poitras V, Pak M, Hong T, Rayner J, Tschakovsky ME. Massage impairs postexercise muscle blood flow and “lactic acid” removal. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010 Jun;42(6):1062-71. [PubMed]

- Franklin NC, Ali MM, Robinson AT, Norkeviciute E, Phillips SA. Massage Therapy Restores Peripheral Vascular Function After Exertion. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. June 2014. Volume 95, Issue 6, Pages 1127–1134. [Link]

- Monedero J, Donne B. Effect of recovery interventions on lactate removal and subsequent performance. Int J Sports Med 2000; 21: 593-7. [PubMed]

- Bale P, James H. Massage, warmdown and rest as recuperative measures after short term intense exercise. Physiother Sport 1991; 13: 4-7.

- Dolgener F, Morien A. The effect of massage on lactate disappearance. J Strength Cond Res 1993; 7 (3): 159-62. [Link]

- Gupta S, Goswami A, Sadhukhan A, et al. Comparative study of lactate removal in short term massage of extremities, active recovery and a passive recovery period after supramaximal exercise sessions. Int J Sports Med 1996; 217 (2): 106-10. [PubMed]

- Hemmings B, Smith M, Gradon J, et al. Effects of massage on physiological restoration, perceived recovery, and repeated sports performance. Br J Sports Med 2000; 34: 109-15. [Link]

- Micklewright, D. P., Beneke, R., Gladwell, V., & Sellens, M. H. (2003). Blood lactate removal using combined massage and active recovery. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 35(5), Supplement abstract 1755. [Link]

- Leivadi S, Hernandez-Reif M, Field T, et al. Massage therapy and relaxation effects on university dance students. J Dance Med Sci 1999; 3 (3): 108-12. [Link]

- Hernandez-Reif M, Field T, Krasnegor J, et al. Lower back pain is reduced and range of motion increased after massage therapy. Int J Neurosci 2001; 106: 131-45. [PubMed]

- Field T, Grizzle N, Scafidi F, et al. Massage and relaxation therapies’ effects on depressed adolescent mothers. Adolescence 1997; 31 (124): 903-1003. [PubMed]

- Ironson G, Field T, Scafidi F, et al. Massage therapy is associated with enhancement of the immune system’s cytotoxic capacity. Int J Neurosci 1996; 84: 205-17. [PubMed]

- Moyer CA, Seefeldt L, Mann ES, Jackley LM. Does massage therapy reduce cortisol? A comprehensive meta-analysis. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2011 Jan; 15(1): 3-14. Epub 2010 Jul 2. [PubMed]

- Weerapong P, Hume PA, and Kolt GS. The mechanisms of massage and effects on performance, muscle recovery, and injury prevention. Sports Med 35: 235–256, 2005. [PubMed]

- Thomson D. Gupta A, Arundell J, Crosbie J. Deep soft-tissue massage applied to healthy calf muscle has no effect on passive mechanical properties: a randomized, single-blind, cross-over study. BMC Sports Science, Medicine, and Rehabilitation (2015) 7:21. [PubMed]

- Hopper D, Conneely M, Chromiak F, Canini E, Berggren J, Briffa K. Evaluation of the effect of two massage techniques on hamstring muscle length in competitive female hockey players. Physical Therapy in Sport Volume 6, Issue 3, August 2005, Pages 137–145. [Link]

- McKechnie GJB, Young WB, Behm DG. Acute effects of two massage techniques on ankle joint flexibility and power of the plantar flexors. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine (2007) 6, 498-504. [PubMed]

- Mudie K, Thomson D, Crosbie J, Gupta A. Acute effects of massage on passive ankle stiffness following an exhaustive stretch-shorten cycle task: A pilot study. Conference: 24th International Society of Biomechanics in Sports. [Link]

- Stanley S, Purdam C, Bond T, et al. Passive tension and stiffness properties of the ankle plantar flexors: the effects of massage abstract]. XVIIIth Congress of the International Society of Biomechanics; 2001 Jul 8-13; Zurich.

- Gleim GW, McHugh MP. Flexibility and its effects on sports injury and performance. Sports Med 1997; 24 (5): 289-99. [PubMed]

- Nordschow M, Bierman W. The influence of manual massage on muscle relaxation: effect on trunk flexion. J Am Phys Ther 1962; 42 (10): 653-7. [PubMed]

- Wiktorsson-Möller M, Oberg B, Ekstrand J, Gillquist J. Effects of warming up, massage, and stretching on range of motion and muscle strength in the lower extremity. Am J Sports Med. 1983 Jul-Aug;11(4):249-52. [PubMed]

- Chunco R. The Effects of Massage on Pain, Stiffness, and Fatigue Levels Associated with Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Case Study. International Journal of Therapeutic Massage and Bodywork. 4(1), March 2011. [PubMed]

- Corley M, Ferriter J, Zeh J, et al. Physiological and psychological effects of back rubs. Appl Nurs Res 1995; 8 (1): 39-43. [PubMed]

- Fraser J, Kerr J. Psychological effects of back massage on elderly institutionalized patients. J Adv Nurs 1993; 18: 238-45. [PubMed]

- Groer M, Mozingo J, Droppleman P, et al. Measures of salivary secretary immunoglobulin A and state anxiety after a nursing back rub. Appl Nurs Res 1994; 7 (1): 2-6. [PubMed]

- Labyak S, Metzger B. The effects of effleurage backrub on the physiological components of relaxation: a meta-analysis. Nurs Res 1997; 46 (1): 59-62. [PubMed]

- Kaada B, Torsteinbo O. Increase of plasma beta-endorphins in connective tissue massage. Gen Pharmacol 1989; 20 (4): 487-9. [PubMed]

- Delaney J, Leong K, Watkins A, et al. The short-term effects of myofascial trigger point massage therapy on cardiac autonomic tone in healthy subjects. J Adv Nurs 2002; 37 (4): 364-71. [PubMed]

- Lee YH, Park BNR, and Kim SH. The Effects of Heat and Massage Application on Autonomic Nervous System. Yonsei Med J. 2011 Nov 1; 52(6): 982–989. [PubMed]

- Diego MA, Field T. Moderate pressure massage elicits a parasympathetic nervous system response. Int J Neurosci. 2009;119(5):630-8. [PubMed]

- Supa’at I, Zakaria Z, Maskon O, Aminuddin A, AnitaMegat N, Nordin M. Effects of Swedish Massage Therapy on Blood Pressure, Heart Rate, and Inflammatory Markers in Hypertensive Women. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013. [PubMed]

- Guan L, Collet JP, Yuskiv N, Skippen P, Brant R, Kissoon N. The Effect of Massage Therapy on Autonomic Activity in Critically Ill Children. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine Volume 2014 (2014), Article ID 656750, 8 pages. [Link]

- Fazeli S, Pourrahmat M, Mailan L, Guan L, Collet JP. The Effect of Head Massage on the Regulation of the Cardiac Autonomic Nervous System: A Pilot Randomized Crossover Trial. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. January 2016, 22(1): 75-80. [Link]

- Resnick PB, Comparing the Effects of Rest and Massage on Return to Homeostasis Following Submaximal Aerobic Exercise: a Case Study. The International Journal of Therapeutic Massage & Bodywork. 9(1). [Link]

- Guan L. (2012). The effect of massage on autonomic nervous system in patients in pediatric intensive care units. MSc Thesis. [Link]

- Delaney, JP, Leong KS, Watkins A, Brodie D. (2002). The short-term effects of myofascial TrPTs massage therapy on cardiac autonomic tone in healthy subjects. Journal of Advanced Nursing 37(4):364-71. [Link]

- Givi M. Durability of Effect of Massage Therapy on Blood Pressure. Int J Prev Med. 2013 May; 4(5): 511–516. [PubMed]

- Moeini M, Givi M, Ghasempour Z, and Sadeghi M. The effect of massage therapy on blood pressure of women with pre-hypertension. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2011 Winter; 16(1): 61–70. [PubMed]

- Trimble, M., & Harp, S. (1998). Postexercise potentiation of the H-reflex in humans. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 30(6), 933-94. [PubMed]

- Folland, J.P., Wakamatsu, T., & Fimland, M.S. (2008). The influence of maximal isometric activity on twitch and H-reflex potentiation, and quadriceps femoris performance. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 10(4), 739-748. [PubMed]

- Morelli M, Seaborne D, Sullivan S. Changes in H-reflex amplitude during massage of triceps surae in healthy subjects. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1990; 12 (2): 55-9. [PubMed]

- Morelli M, Seaborne D, Sullivan S. H-reflex modulation during Sport manual muscle massage of human triceps surae. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1991; 72: 915-9.

- Morelli M, Chapman C, Sullivan S. Do cutaneous receptors contribute to the changes in the amplitude of the H-reflex during massage? Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol 1999; 39 441-7. [PubMed]

- Sullivan S, Williams L, Seaborne D, et al. Effects of massage on alpha motoneuron excitability. Phys Ther 1991; 71 (8): 555-60. [PubMed]

- Goldberg J, Sullivan SJ, Seaborne DE. The effect of two intensities of massage on h-reflex amplitude. Phys Ther. 1992;72:449–57. [PubMed]

- Crawford C, Boyd C, Paat CF, Price A, Xenakis L, Yang E, Zhang W. The Impact of Massage Therapy on Function in Pain Populations-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials: Part I, Patients Experiencing Pain in the General Population. Pain Med. 2016 May 10. pii: pnw099. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed]

- Gam A, Warming S, Larsen L, et al. Treatment of myofascial trigger-points with ultrasound combined with massage and exercise: a randomized controlled trial. Pain 1998; 77: 73-9. [PubMed]

- Pope M, Phillips R, Haugh L, et al. A prospective randomized three-week trial of spinal manipulation, transcutaneous muscle stimulation, massage and corset in the treatment of subacute low back pain. Spine 1994; 19 (22): 2571-7. [PubMed]

- Puustjarvi K, Airaksinen O, Pontinen P. The effects of massage in the patients with chronic tension headache. Acupunct Electrother Res 1990; 15: 159-62. [PubMed]

- Nunes GS, Bender PU, de Menezes FS, Yamashitafuji I, Vargas VZ, Wageck B. Massage therapy decreases pain and perceived fatigue after long-distance Ironman triathlon: a randomised trial. J Physiother. 2016 Apr;62(2):83-7. [PubMed]

- Visconti L, Capra G, Carta G, Forni C, Janin D. Effect of massage on DOMS in ultramarathon runners: A pilot study. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2015 Jul;19(3):458-63. [PubMed]

- Jane, S.W., Wilkie, D.J., Gallucci, B.B., Beaton, R.D., Huang, H.Y., (2008). Effects of a Full-Body Massage on Pain Intensity, Anxiety, and Physiological Relaxation in Taiwanese Patients with Metastatic Bone Pain: A Pilot Study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 37(4):754-63. [PubMed]

- Moraska, A., Chandler, C.(2008). Changes in Clinical Parameters in Patients with Tension-type Headache Following Massage Therapy: A Pilot Study. J Man Manip Ther. 16(2), 106-12. [PubMed]

- Mitchinson, A.R., Kim, H.M., Rosenberg, J.M., Geisser, M., Kirsh, M., Cikrit, D., Hinshaw, D.B. (2007). Acute postoperative pain management using massage as an adjuvant therapy: a randomized trial. Arch Surg. 142(12), 1158-67. [PubMed]

- Mehling, W.E., Jacobs, B., Acree, M., Wilson, L., Bostrom, A., West, J., Acquah, J., Burns, B., Chapman, J., Hecht, F.M. (2007). Symptom management with massage and acupuncture in postoperative cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 33(3), 258-66. [PubMed]

- Kshettry, V.R., Carole, L.F., Henly, S.J., Sendelbach, S., Kummer, B. (2006). Complementary alternative medical therapies for heart surgery patients: feasibility, safety, and impact. Ann Thorac Surg. 81(1), 201. [PubMed]

- Chen, H.M., Chang, F.Y., Hsu, C.T. (2005). Effect of acupressure on nausea, vomiting, anxiety and pain among post-cesarean section women in Taiwan. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 21(8), 341-50. [PubMed]

- Wang, H.L., Keck, J.F. (2004). Foot and hand massage as an intervention for postoperative pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 5(2), 59-65. [PubMed]

- Piotrowski, M.M., Paterson, C., Mitchinson, A., Kim, H.M., Kirsh, M., Hinshaw, D.B. (2003). Massage as adjuvant therapy in the management of acute postoperative pain: a preliminary study in men. J Am Coll Surg. 197(6), 1037-46. [PubMed]

- Taylor, A.G., Galper, D.I., Taylor, P., Rice, L.W., Andersen, W., Irvin, W., Wang, X.Q., Harrell, F.E. Jr. (2003). Effects of adjunctive Swedish massage and vibration therapy on short-term postoperative outcomes: a randomized, controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. 9(1), 77-89. [PubMed]

- Le Blanc-Louvry, I., Costaglioli, B., Boulon, C., Leroi, A.M., Ducrotte, P. (2002). Does mechanical massage of the abdominal wall after colectomy reduce postoperative pain and shorten the duration of ileus? Results of a randomized study. J Gastrointest Surg. 6(1), 43-9. [PubMed]

- Hattan, J., King, L., Griffiths, P. (2002). The impact of foot massage and guided relaxation following cardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 37(2), 199-207. [PubMed]

- Hulme, J., Waterman, H., Hillier, V.F. (1999). The effect of foot massage on patients’ perception of care following laparoscopic sterilization as day case patients. J Adv Nurs. 30(2), 460-8. [PubMed]

- Nixon, M., Teschendorff, J., Finney, J., Karnilowicz, W. (1997). Expanding the nursing repertoire: the effect of massage on post-operative pain. Aust J Adv Nurs. 14(3), 21-6. [PubMed]

- Field, T., Figueiredo, B., Hernandez-Reif, M., Diego, M., Deeds, O., Ascencio, A. (2008). Massage therapy reduces pain in pregnant women, alleviates prenatal depression in both parents and improves their relationships., J Bodyw Mov Ther. 12(2), 146-50. [PubMed]

- Suresh, S., Wang, S., Porfyris, S., Kamasinski-Sol, R., Steinhorn, D.M. (2008). Massage therapy in outpatient pediatric chronic pain patients: do they facilitate significant reductions in levels of distress, pain, tension, discomfort, and mood alterations?, Paediatr Anaesth. 18(9), 884-7. [PubMed]

- Hughes, D., Ladas, E., Rooney, D., Kelly, K. (2008). Massage therapy as a supportive care intervention for children with cancer, Oncol Nurs Forum. 35(3), 431-42. [PubMed]

- Lowe, R.M., Hashkes, P.J. (2008). Growing pains: a noninflammatory pain syndrome of early childhood. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 4(10), 542-9. [PubMed]

- Walach, H., Güthlin, C., König, M. (2003). Efficacy of massage therapy in chronic pain: a pragmatic randomized trial. J Altern Complement Med. 9(6), 837-46. [PubMed]

- Seers, K., Crichton, N., Martin, J., Coulson, K., Carroll, D. (2008). A randomised controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of a single session of nurse administered massage for short term relief of chronic non-malignant pain. BMC Nurs. 7, 10. [PubMed]

- Frey Law, L.A., Evans, S., Knudtson, J. Nus, S., Scholl, K., Sluka, K.A. (2008). Massage reduces pain perception and hyperalgesia in experimental muscle pain: a randomized, controlled trial. J Pain. 9(8), 714-21. [PubMed]

- Currin, J., Meister, E.A. (2008). A hospital-based intervention using massage to reduce distress among oncology patients. Cancer Nurs. 31(3), 214-21. [PubMed]

- Sagar, S.M., Dryden, T., Wong, R.K. (2007). Massage therapy for cancer patients: a reciprocal relationship between body and mind. Curr Oncol. 14(2), 45-56. [PubMed]

- Moraska, A., Chandler, C., Edmiston-Schaetzel, A., Franklin, G., Calenda, E.L., Enebo, B. (2008). Comparison of a targeted and general massage protocol on strength, function, and symptoms associated with carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomized pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 14(3), 259-67. [PubMed]

- Quinn, F., Hughes, C.M., Baxter, G.D. (2008). Reflexology in the management of low back pain: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 16(1), 3-8. [PubMed]

- Bell, J. (2008). Massage therapy helps to increase range of motion, decrease pain and assist in healing a client with low back pain and sciatica symptoms. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 12(3), 281-9. [PubMed]

- Hsieh, L.L., Kuo, C.H., Lee, L.H., Yen, A.M., Chien, K.L., Chen, T.H. (2006). Treatment of low back pain by acupressure and physical therapy: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 332(7543), 696-700. [PubMed]

- Dryden, T., Baskwill, A., Preyde, M. (2004). Massage therapy for the orthopaedic patient: a review. Orthop Nurs. 23(5), 327-32. [PubMed]

- Brady, L.H., Henry, K., Luth, J.F. 2nd, Casper-Bruett, K.K. (2001). The effects of shiatsu on lower back pain. J Holist Nurs. 19(1), 57-70. [PubMed]

- Cherkin, D.C., Eisenberg, D., Sherman, K.J., Barlow, W., Kaptchuk, T.J., Street, J., Deyo, R.A. (2001). Randomized trial comparing traditional Chinese medical acupuncture, therapeutic massage, and self-care education for chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 161(8), 1081-8. [PubMed]

- Lang, T., Hager, H., Funovits, V., Barker, R., Steinlechner, B., Hoerauf, K., Kober, A. (2007). Prehospital analgesia with acupressure at the Baihui and Hegu points in patients with radial fractures: a prospective, randomized, double-blind trial. Am J Emerg Med. 25(8), 887-93. [PubMed]

- Arai, Y.C., Ushida, T., Osuga, T., Matsubara, T., Oshima, K., Kawaguchi, K., Kuwabara, C., Nakao, S., Hara, A., Furuta, C., Aida, E., Ra, S., Takagi, Y., Watakabe, K. (2008). The effect of acupressure at the extra 1 point on subjective and autonomic responses to needle insertion. Anesth Analg. 107(2), 661-4. [PubMed]

- Guyton A, Hall J. Textbook of medical physiology. 10th ed. Philadelphia (PA): WB Saunders Company, 2000. [Link]

- Sommer C. Serotonin in pain and analgesia: actions in the periphery. Mol Neurobiol. 2004 Oct;30(2):117-25. [PubMed]

- Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Diego M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C. Cortisol decreases and serotonin and dopamine increase following massage therapy. Int J Neurosci. 2005 Oct;115(10):1397-413. [PubMed]

- van den Dolder PA, Ferreira PH, Refshauge KM. Effectiveness of soft tissue massage and exercise for the treatment of non-specific shoulder pain: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2014;48(16):1216–26. [PubMed]

- Bronfort G, Haas M, Evans R, Leininger B, Triano J. Effectiveness of manual therapies: The UK evidence report. Chiropr Osteopat 2010;18:3. doi:10.1186/ 1746-1340-18-3. [PubMed]

- Furlan AD, Giraldo M, Baskwill A, Irvin E, Imamura M. Massage for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;9:CD001929. doi: 10.1002/ 14651858. [PubMed]

- Kumar S, Beaton K, Hughes T. The effectiveness of massage therapy for the treatment of nonspecific low back pain: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Int J Gen Med 2013;6:733–41. [Link]

- Netchanok S, Wendy M, Marie C, Siobhan O. The effectiveness of Swedish massage and traditional Thai massage in treating chronic low back pain: A review of the literature. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2012;18(4):227–34. [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Reif, M., Shor-Posner, G., Baez, J., Soto, S., Mendoza, R., Castillo, R., Quintero, N., Perez, E., Zhang, G. (2008). Dominican Children with HIV not Receiving Antiretrovirals: Massage Therapy Influences their Behavior and Development. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med, 5(3):345-354. [PubMed]

- Cooke, M., Holzhauser, K., Jones, M., Davis, C., Finucane, J. (2007). The effect of aromatherapy massage with music on the stress and anxiety levels of emergency nurses: comparison between summer and winter. J Clin Nurs, 16(9):1695-703. [PubMed]

- Engen, D.J., Wahner-Roedler, D.L., Vincent, A., Chon, T.Y., Cha, S.S., Luedtke, C.A., Loehrer, L.L., Dion, L.J., Rodgers, N.J., Bauer, B.A. (2012). Feasibility and effect of chair massage offered to nurses during work hours on stress-related symptoms: a pilot study. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 18(4):212-5. [PubMed]

- Brady, L.H., Henry, K., Luth, J.F. 2nd, Casper-Bruett, K.K. (2001). The effects of shiatsu on lower back pain. J Holist Nurs, 19(1):57-70. [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Reif, M., Field, T., Krasnegor, J., Theakston, H. (2001). Lower back pain is reduced and range of motion increased after massage therapy. Int J Neurosci, 106(3-4):131-45. [PubMed]

- Field, T., Hernandes-Reif, M., Diego, M., Fraser, M. (2007). Lower back pain and sleep disturbance are reduced following massage therapy. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 11(2) 141-145. [Link]

- Moraska, A., Chandler, C. (2009). Changes in Psychological Parameters in Patients with Tension-type Headache Following Massage Therapy: A Pilot Study. J Man Manip Ther. 17(2):86-94. [PubMed]

- Toro-Velasco, C., Arroyo-Morales, M., Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C., Cleland, J.A., Barrero-Hernández, F.J. (2009). Short-term effects of manual therapy on heart rate variability, mood state, and pressure pain sensitivity in patients with chronic tension-type headache: a pilot study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther.32(7):527-35. [PubMed]

- Goffaux-Dogniez, C., Vanfraechem-Raway, R., Verbanck, P. (2003). Appraisal of treatment of the trigger points associated with relaxation to treat chronic headache in the adult. Relationship with anxiety and stress adaptation strategies. 29(5):377-90. [PubMed]

- Fernández-Pérez, A.M., Peralta-Ramírez, M.I., Pilat, A., Villaverde, C. (2008). Effects of myofascial induction techniques on physiologic and psychologic parameters: a randomized controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. 14(7):807-11. [PubMed]

- Billhult, A., Määttä, S. (2008). Light pressure massage for patients with severe anxiety. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 15(2):96-101. [PubMed]

- Mok, E., Woo, C.P. (2004). The effects of slow-stroke back massage on anxiety and shoulder pain in elderly stroke patients. Complement Ther Nurs Midwifery. 10(4):209-16. [PubMed]

- Meeks, T.W., Wetherell, J.L., Irwin, M.R., Redwine, L.S., Jeste, D.V. (2007) Complementary and alternative treatments for late-life depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance: a review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. Oct;68(10):1461-71. [PubMed]

- Field, T., Diego, M., Delgado, J., Garcia, D., Funk, CG. (2011). Hand pain is reduced by massage therapy Complement Ther Clin Pract. November 17(4):226-9. [PubMed]

- Moyer CA, Rounds J, Hannum J. A meta-analysis of massage therapy research. Psychol Bull. 2004 Jan; 130(1):3-18. Abstract at [PubMed]

- McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF. Profile of mood state manual. San Diego (CA): Educational and Industrial Testing Service, 1971. [Link]

- Hemmings B. Sports massage and psychological regeneration Br J Ther Rehabil 2000; 7 (4): 184-8.

- Smith, L. L., Keating, M. N., Holbert, D., Spratt, D. J., McCammon, M. R., Smith, S. S., et al. (1994). The effects of athletic massage on delayed onset muscle soreness, creatine kinase, and neutrophil count: a preliminary report. Journal of Orthopaedic Sports Physical Therapy, 19, 93e99.

- Tejero-Fernandez V, Membrilla-Mesa M, Galiano-Castillo N, Arroyo-Morales M. Immunological effects of massage after exercise: A systematic review. Physical Therapy in Sport 16 (2015) 187-192. [PubMed]

- Hilbert, J. E., Sforzo, G. A., & Swensen, T. (2003). The effects of massage on delayed onset muscle soreness. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 37, 72-75. [PubMed]

- Arroyo-Morales, M., Olea, N., Ruíz, C., del Castilo Jde, D., Martínez, M., Lorenzo, C., et al. (2009). Massage after exercise-responses of immunologic and endocrine markers: a randomized single-blind placebo-controlled study. Journal Strength Conditioning and Research, 23, 638e644. [PubMed]

- Rapaport MH. Schettler PJ. Bresee C. A preliminary study of the effects of a single session of Swedish massage on hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal and immune function in normal individuals. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:1079–1088. Free full-text at [PubMed]

- Rapaport MH, Schettler P, Bresee C. A preliminary study of the effects of repeated massage on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and immune function in healthy individuals: A study of mechanisms of action and dosage. J Altern Complement Med. Aug 2012; 18(8): 789–797. Free full-text at [PubMed]

- Stock, C., Baum, M., Rosskopf, P., Schober, F., Weiss, M., & Liesen, H. (1996). Electroencephalogram activity, catecholamines, and lymphocyte subpopulations after resistance exercise and during regeneration. European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology, 72, 235-241. [PubMed]

- Walton T. 5 Myths and Truths about Massage Therapy Letting Go Without Losing Heart. Massage Therapy Foundation. [Link]