Contents of Article

- Summary

- What is Olympic Weightlifting?

- Why is Olympic Weightlifting useful for sports?

- Is Power Development important in Olympic Weightlifting?

- Biomechanical similarities to sporting movements

- How do you train for Olympic Weightlifting?

- Should I use Olympic Weightlifting or not?

- What future research is needed for Olympic Weightlifting?

- Conclusion

- References

- About the Author

Summary

Olympic Weightlifting exercises are reported to be a common component in the strength and conditioning programmes of many high school and professional athletes. This is primarily due to their biomechanical similarities to many sporting movements, and their manifestation of large force and power qualities in comparison to other exercises.

Though there are common disagreements between exercise professionals with regards to Olympic Weightlifting’s transferability to sport performance, the current substantial body of evidence suggests they are an effective tool for enhancing athleticism. However, to further our current understanding of the usefulness of Olympic Weightlifting for athletic performance, more research is needed.

What is Olympic Weightlifting?

Technically speaking, Olympic Weightlifting, otherwise known as ‘weightlifting’ or ‘Olympic-style weightlifting’ is a registered sport that incorporates the use of two independent lifts that require the athlete to lift a loaded barbell from the floor to an overhead position in an explosive manner. The two lifts, the ‘Clean & Jerk’ and the ‘Snatch’ are explosive movements as they require a combination of maximal strength and maximal speed.

On the other hand, these exercises and their variations are an effective method for enhancing athletic performance (1). Sports that require high-load speed strength such as football, volleyball, basketball, and track and field, have all been suggested to benefit from the use of Olympic Weightlifting because of their biomechanical characteristics of high force and power output (2, 3).

It is often discussed that Olympic Weightlifting and Powerlifting were named the wrong way around, so that Olympic Weightlifting should rightly be named as Powerlifting as it is a power-based sport, in comparison to Powerlifting which is actually a strength-based sport. Though this may be true, this is just a matter of semantics.

Why is Olympic Weightlifting useful for sports?

It has been reported that large percentages of strength and conditioning coaches in High School (97%), the National Football League (88%), National Hockey League (100%), and the National Basketball League (95%) incorporate the use of Olympic Weightlifting in their training programmes (4, 5, 6, 7). As so many coaches use this training method to enhance athletic performance, it would appear that Olympic Weightlifting is a highly-regarded training tool. The two primary reasons Olympic Weightlifting is so popular amongst strength and conditioning coaches are for:

- Power Development (strength-speed)

- Biomechanical similarities to sporting movements (kinematic and kinetic)

Is Power Development important in Olympic Weightlifting?

As power is a vital aspect of the performance of many sports, findings ways to optimise athletic power is of great importance (8). It has been suggested there are seven independent qualities that contribute to an athlete’s ability to generate power (9). These are:

- Maximum strength

- High-load speed strength, or strength-speed (> 30 % of 1 repetition maximum (RM))

- Low-load speed strength, or speed-strength (< 30 % of 1RM)

- Rate of force development

- Reactive strength

- Power endurance

- Skill performance

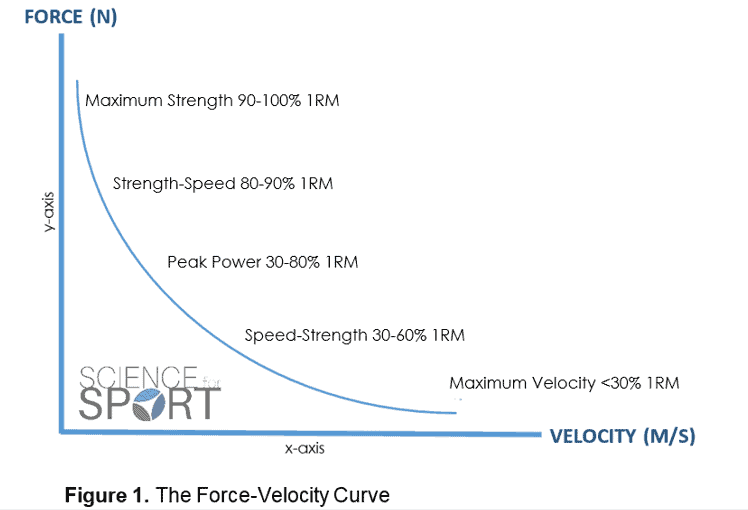

In most circumstances, the Olympic Weightlifting movements fall into the strength-speed component of the force-velocity curve (Figure 1) and thus improve the strength-speed quality listed above. This is simply because these exercises require an athlete to move heavy loads as quickly as possible – requiring a high level of explosive strength.

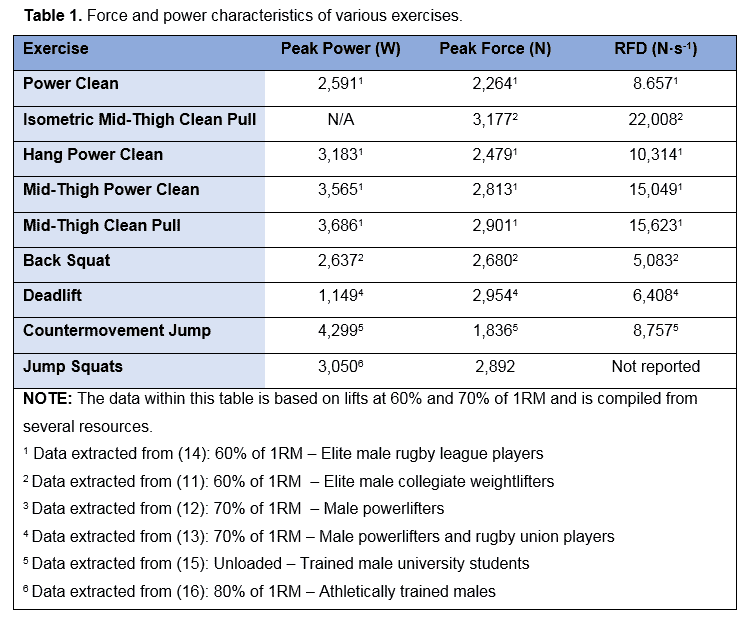

Therefore, as the Clean & Jerk and the Snatch are powerful exercises, they are often used as favourable tools for developing explosive strength in athletes (10). These exercises and their variations have been shown to produce tremendous levels of force and power in comparison to other strength- and power-based exercises such as the back squat, deadlift, and jump squat (Table 1). In fact, the isometric mid-thigh clean pull has been recorded to produce a rate of force development (RFD) of 22,000 N·s-1 (11) in comparison to that of a back squat and deadlift which were recorded to produce only 5,000 N·s-1 (12) 6,400 N·s-1 (13), respectively.

Training programmes consisting entirely of Olympic Weightlifting have been shown to improve jump, sprint, and balance performances (17, 18). What’s more, performances during the hang power clean have been correlated with sprint and vertical jump performances – suggesting that better hang clean performances can result in better jump and sprint abilities (19). This may also be supported by Carlock et al., (2004) (20) who found a direct relationship between a group of USA National weightlifters’ performances and their peak power outputs during vertical jumps. This simply implies that weightlifters’ who perform better, are also able to jump higher.

Furthermore, as higher rates of force development are linked with better jump (21, 22, 23), sprint (24), cycling (25) and golf swing performances (26), and Olympic Weightlifting movements have been shown to produce tremendous levels of rate of force development, then this form of training may be extremely useful for developing explosiveness. To support this argument further, Olympic Weightlifting movements have been shown to have a direct relationship with the rate of force development (23, 27).

For the reasons listed below, strength and conditioning coaches often find strong justification for the inclusion of OWL in their programmes for the development of explosive strength.

- They train the strength-speed component of the force-velocity curve.

- They produce tremendous levels of explosive force and power.

- Have shown relationships with jump and sprint performances.

- Have been shown to improve jump, sprint and balance performances.

- Have been shown to have a direct relationship with the rate of force development.

Biomechanical similarities to sporting movements

In addition to the aforementioned reasons for using Olympic Weightlifting to improve athletic performance, their compelling similarities to many sporting movements also offers reasoning.

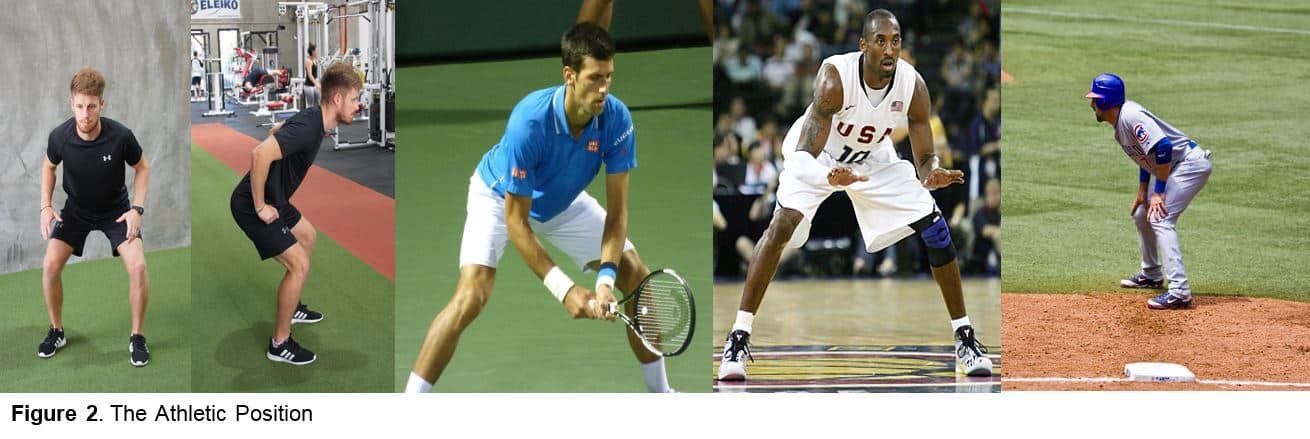

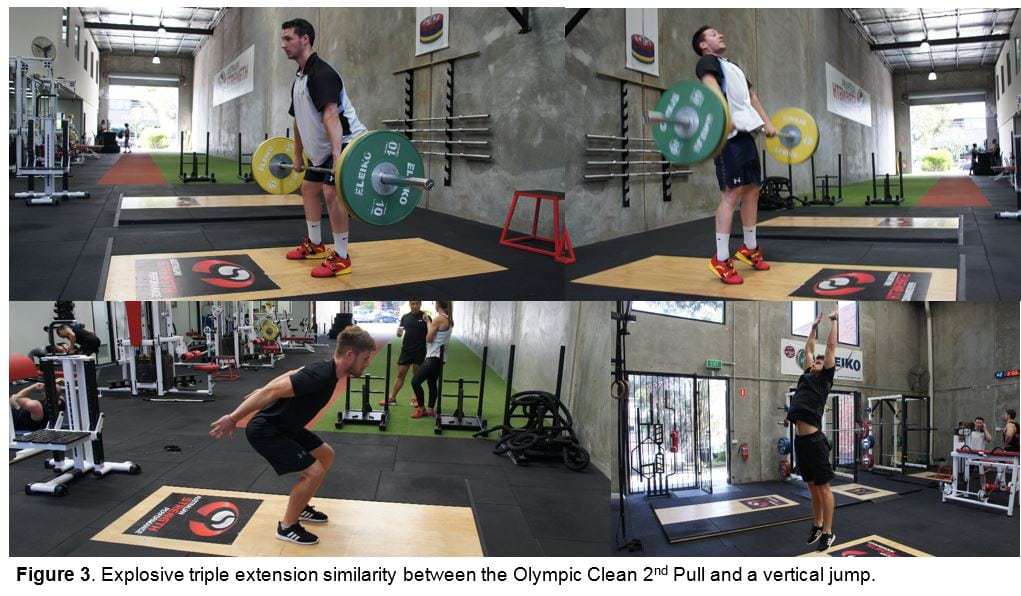

The ‘athletic position’ and the ‘triple extension’ which are apparent in many sports (Figures 2 and 3) are also obvious during the Clean & Jerk and Snatch. Therefore, improving an athlete’s ability to explosive react from these positions would seem an obvious reason to include the Olympic Weightlifting movements.

The Athletic Position

In comparison to the triple extension, the use of Olympic Weightlifting to enhance an athlete’s ability to adapt and eject from the athletic position gets very little attention.

The starting position during the second pull phase of the Clean and the Snatch has an observable similarity to the athletic position (Figures 2 and 3). It has also been identified that the second pull phases during the Clean and Snatch and the drive phase during the Jerk all have remarkable kinetic and kinematic similarities to jumping (28, 10).

An interesting finding by Gourgoulis et al., (2009) (29) was that a successful performance during the Snatch was dictated by the acceleration force vector applied to the barbell. In other words, this means the magnitude and the direction of the acceleration force – how much force is applied, and in what direction. And as we already know the second pull produces the greatest levels of force, then getting the athlete into an excellent second pull position may be vital so that they can apply the largest forces to the barbell and in the optimal direction – if they want a successful lift that is. If so, then getting an athlete to adopt an optimal second pull position is essential.

It is at this point where the dynamic correspondence of Olympic Weightlifting may come into play. If you can teach an athlete to successfully perform Olympic Weightlifting movements, then perhaps they are optimising their mechanics to jump – as we have already mentioned the two are remarkably similar. This would include optimising their second pull position, which is also observably similar to the athletic position.

So the thought is, if an athlete can successfully perform complex Olympic Weightlifting movements, then perhaps they are optimising their mechanics to do so. And as the mechanics of the second pull start positon are similar to the athletic position, and the pulling phase of the Clean and Snatch and the drive phase of the Jerk are similar to jumping, then there is reason to suggest some degree of dynamic correspondence between Olympic Weightlifting and both adopting and ejecting from the athletic position.

One thought-provoking concept that is very rarely discussed is the ability of the drop-under and catch phases of the Clean and Snatch to enhance performance. Though coaches often neglect the drop-under and catch phases of the lifts out of their training programmes, these two segments may offer unique benefits. These being:

- The rapid drop-under movement which requires an athlete to move from full triple extension into triple flexion (similar to the athletic position) in an extremely short period of time (110-340 milliseconds) (30, 31).

- The high eccentric peak force and rate of development experienced during the heavy eccentric loading of the catch phase.

- Potential postural strength and stability developments gained from the catch phases – particularly from the Snatch.

Though these are very interesting and fundamental points, they are beyond the scope of this article and will be touched on in greater detail at a later date.

The Triple Extension

The triple extension* which is apparent in many sports is, as previously discussed, biomechanically similar to the start of the second pull phase during the Clean and Snatch and the drive phase of the Jerk. This, combined with its ability to produce the largest force and power outputs, means the second pull and drive phase is often used as a favourable tool to develop strength-speed (i.e. explosive strength).

*The triple extension refers to the explosive action produced by the simultaneous extension of the hips, knees, and ankles. This bilateral or unilateral extension movement is extremely common in sports (e.g. sports involving any sprinting and jumping).

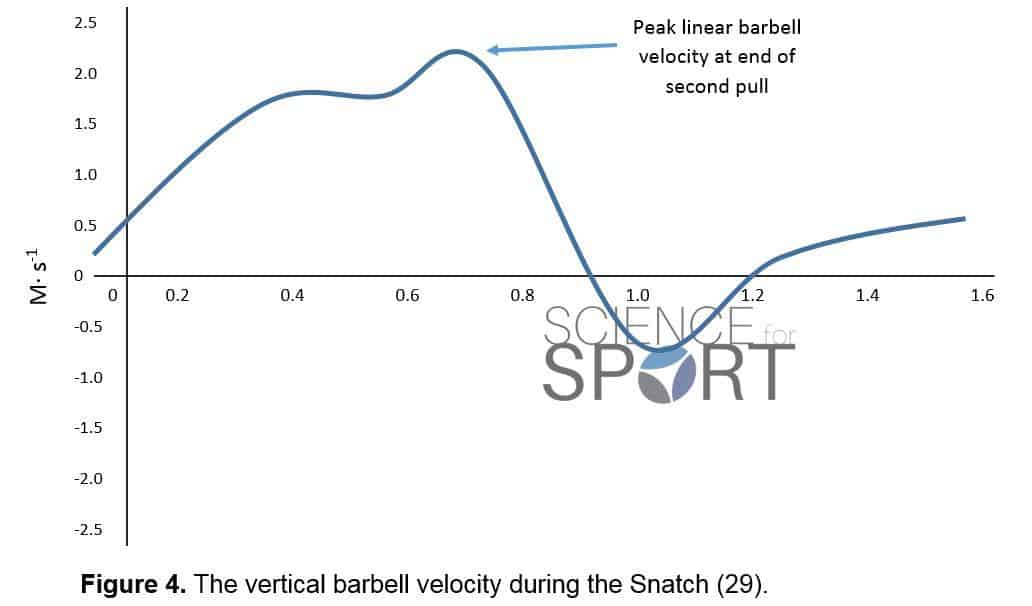

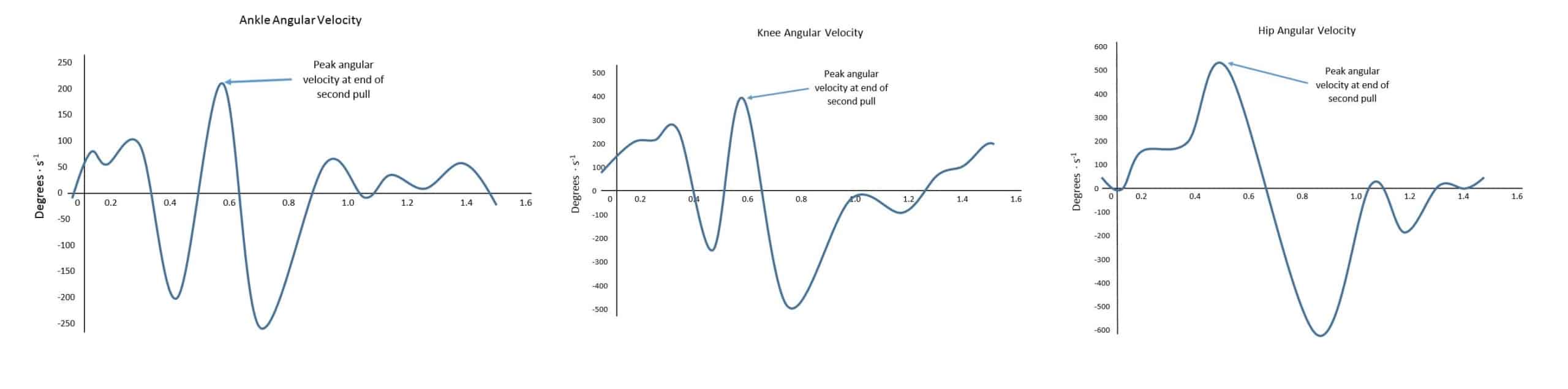

Another benefit to the use of Olympic Weightlifting movements is the acceleration pattern of the barbell and ankle, knee, and hip joints observed throughout the second pull and the drive phase (29). During these movements, the speed of the barbell continues to increase up until the end of the second pull or drive phase (Figure 4).

This concept also applies to the ankle, knee, and hip joints which all experience an increase in angular velocity towards the end of the second pull (Figure 5). As the fastest portion of these lifts is experienced at the very end of the movement, this suggests that Olympic Weightlifting movements are somewhat similar to ballistic exercises. This implies that unlike strength training exercises such as the back squat, Olympic Weightlifting or ballistic exercises experience no deceleration at the end of the movement. As a result, this continual movement acceleration is similar to that of jumping and sprinting.

In summary, it is the combination of their large force and power outputs and similarities to sporting movements which leads exercise professionals to believe Olympic Weightlifting can have a large dynamic correspondence with sport-specific performances.

How do you train for Olympic Weightlifting?

Having read the previous sections, it is clear why strength and conditioning coaches will often use Olympic Weightlifting to improve athletic performance. However, these lifts are only used for improving athletic performance, but also as a tool for monitoring performance and the effectiveness of their training programme.

Recall earlier that there are seven independent qualities that contribute to an athlete’s ability to generate power (9):

- Maximum strength

- High-load speed strength, or strength-speed (> 30 % of 1RM)

- Low-load speed strength, or speed-strength (< 30 % of 1RM)

- Rate of force development

- Reactive strength

- Power endurance

- Skill performance

As each sport requires a different combination of these qualities, testing an athlete’s ability to perform each one provides the strength and conditioning coach with a blueprint for training prescription. This simply means that if the coach understands their athlete’s weaknesses, in terms of the power qualities listed above, then they can design the training programme more specifically. To add to this, it has been proposed that training the athlete’s weakest power qualities will result in the greatest performance improvements (9) – so understanding the athlete’s strengths and weaknesses is vital.

Due to the inaccessibility of most laboratory equipment in practical environments, strength and conditioning coaches will often use the 1RM back squat, 1RM power clean, and a vertical jump to analyse the power profile of their athletes. Each exercise is used to analyse power capacity in a different manner:

- 1RM Back Squat – Maximum strength

- 1RM Power Clean – Strength-speed

- Vertical jump – Speed-strength

Analysing these three aspects provides the coach with an understanding of the athlete’s ability to generate power. Therefore, the coach can understand that if an athlete’s vertical jump is good, but their 1RM power clean is not, then the emphasis of training should be to improve their strength-speed ability.

Should I use Olympic Weightlifting or not?

There is often an interesting debate about the effectiveness of Olympic Weightlifting to improve motor skill development and acquisition in sport-specific skills; some critics suggest Olympic Weightlifting cannot improve sport-specific performances due to the movement’s high complexity. For instance, whether a training programme based only on Olympic Weightlifting would improve very particular sport-specific movements (e.g. high-jump take-off) or would they impede upon the performance by confusing complex motor patterns?

Though research has shown that Olympic Weightlifting alone can improve regimented jump, sprint, and balance performances (17, 18), no research to the author’s knowledge has proven that it can enhance complex sport-specific movements (e.g. high jump take-off). However, this is often the case with other forms of training such as hypertrophy, strength, and plyometrics. This debate is built entirely on our lack of understanding between Olympic Weightlifting and its dynamic correspondence.

The debate between Olympic Weightlifting and its effects on sport-specific performance is grounded primarily by the following points:

Arguments for using Olympic Weightlifting

- Demands high neuromuscular coordination and control

- Biomechanical similar to jumping

- Improve movement efficiency and effectiveness

- Large force and power characteristics

- Has been proven to improve jump, sprint, and balance performances

- Trains a particular section on the force-velocity curve (e.g. strength-speed)

- Shown to improve jump RFD – meaning a shift in the force-velocity curve is evident

- Has a direct relationship with the RFD

- Improve axial skeleton rigidness

- Exposure to heavy and rapid eccentric loading

Arguments against using Olympic Weightlifting

- No direct evidence to suggest they can improve motor skill development or acquisition

- The complex high-level skill of Olympic Weightlifting is different to the complex high-level skills associated with sporting movements (e.g. high jump take-off).

- Time-consuming to coach

- The associated risk with moving heavy loads at high speeds

- Expensive equipment

- Requires a large amount of space

- Other exercises can be used to train strength-speed (e.g. Loaded jump squats)

This issue between Olympic Weightlifting and their dynamic correspondence arises when the movement and their application of forces are analysed in further detail. Whilst they appear to imitate sporting movements and also use the same primary joints, muscle groups and ranges of motion, the magnitude (amount) and direction of force application are somewhat different to sport-specific movements (e.g. high jump take-off). This suggests that they are effectively different high-level motor skills despite appearing biomechanically similar. There are three primary biomechanical differences between Olympic Weightlifting and the high jump take-off:

- Force application differences (horizontal and vertical)

- Unilateral (high jump take-off) vs. bilateral (Olympic Weightlifting) movements

- Centre of mass differences

Understanding this information regarding the underpinning biomechanical differences between the Olympic Weightlifting and other complex high-level sport-specific skills is very valuable for programme design. It is this level of in-depth understanding that allows a top-level strength and conditioning specialist to make well-educated judgement towards the specificity of their exercise selection.

Is more future research needed with Olympic Weightlifting?

To advance current understanding of Olympic Weightlifting and its transferability to athletic performance, the following research fields are warranted:

- Direct comparisons between the force-, power-, and velocity-time characteristics of Olympic Weightlifting and other similar strength-power exercises (e.g. jump squats and kettlebell swings).

- Olympic Weightlifting’s ability to improve athletic performance in various populations (i.e. trained and untrained adults, youths, males, females etc).

- Dose-relationships to performance.

Conclusion

Although the concept of using Olympic Weightlifting exercises as a method of improving sport athleticism is not new, there has only been a growing body of research in the past several years. With the recorded levels of force and power outputs expressed during Olympic Weightlifting movements, there is no surprise that they have formed a staple part of many strength and conditioning programmes. Whilst there are suggestions that Olympic Weightlifting may not improve very complex sport-specific skills, current evidence has proven their ability to enhance jump, sprint, and balance performances in controlled testing environments.

Regardless of the concerns regarding whether Olympic Weightlifting can improve sport-specific skills, like many other forms of training, it has been proven to improve regimented forms of athletic performance but has not necessarily been shown to enhance sport-specific skills. As a result, it may be suggested that Olympic Weightlifting is a useful tool to enhance athletic performance.

Lastly, as Olympic weightlifting exercises are recognised as highly-skilled explosive movements, it may be extremely beneficial to educate early specialisation of the lifts in an attempt to maximise later life skill acquisition and therefore their transferable effect to sporting performance.

- Hori, M.S., Newton, R.U., Nosaka, K., Stone, M.H. (2005). Weightlifting Exercises Enhance Athletic Performance That Requires High-Load Speed Strength. National Strength and Conditioning Association, 27(4), pp.50-55. [Link]

- Hoffman, J.R., J. Cooper, M. Wendell, and J. Kang. Comparison of Olympic vs. traditional power lifting training programs in football players. J. Strength Cond. Res. 18(1):129–135. 2004. [PubMed]

- Stone, M.H., R. Byrd, J. Tew, and M. Wood. Relationship between anaerobic power and Olympic weightlifting performance. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness. 20:99–102. 1980. [PubMed]

- Duehring, MD, Feldmann, CR, and Ebben, WP. Strength and conditioning practices of United States high school strength and conditioning coaches. J Strength Cond Res 23(8): 2188–2203, 2009. [PubMed]

- Ebben, W.P., and Blackard, D.O. (2001). Strength and conditioning practice of National Football League strength and conditioning coaches Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 15, pp.48–58. [PubMed]

- Simenz, C.J., Dugan, CA, and Ebben, WP. Strength and conditioning practice of National Basketball Association strength and conditioning coaches. J Strength Cond Res 19: 495–504, 2005. [PubMed]

- Ebben, WP, Carroll, RM, and Simenz, C. Strength and conditioning practice of National Hockey League strength and conditioning coaches. J Strength Cond Res 18: 889–897, 2004. [PubMed]

- Docherty, D, Robbins, D, and Hodgson, M. (2004). Complex training revisited: A review of its current status as a viable training approach. Strength Cond J, 27(4), pp.50-55. [Link]

- Newton, R.U., and E. Dugan. Application of strength diagnosis. Strength Cond. J. 24(5):50–59. 2002. [Link]

- Garhammer, J. & Gregor, R. (1992). Propulsion Forces as a Function of Intensity for Weightlifting and Vertical Jumping, Appl. Sports Sci. Research, 6(3): 129-134. [Link]

- Kawamori, N., S.J. Rossi, B.D. Justice, E.E. Haff, E.E. Pistilli, H.S. O’Bryant, M.H. Stone, and G.G. Haff. Peak force and rate of force development during isometric and dynamic mid-thigh clean pulls performed at various intensities. Strength Cond. Res. 20(3):483–491. 2006 [PubMed]

- Swinton, PA, Lloyd, R, Keogh, JWL, Agouris, I, and Stewart, AD. A biomechanical comparison of the traditional squat, powerlifting squat, and box squat. J StrengthCond Res 26(7): 1805–1816, 2012. [PubMed]

- Swinton, PA, Stewart, AD, Keogh, JWL, Agouris, I, and Lloyd, R. Kinematic and kinetic analysis of maximal velocity deadlifts performed with and without the inclusion of chain resistance. J Strength Cond Res 25(11): 3163–3174, 2011 [PubMed]

- Comfort, P, Allen, M, and Graham-Smith, P. Kinetic comparisons during variations of the power clean. J Strength Cond Res 25(12): 3269–3273, 2011. [PubMed]

- Hori, N, Newton, RU, Kawamori, N,McGuigan,MR, Kraemer,WJ, and Nosaka, K. Reliability of performance measurements derived from ground reaction force data during countermovement jump and the influence of sampling frequency. J Strength Cond Res 23(3): 874–882, 2009 [PubMed]

- McBride, J. M., T. Triplett-McBride, A. Davie, and R. U. Newton. The effect of heavy- vs. light-load jump squats on the development of strength, power, and speed. J. Strength Cond. Res. 16(1):75–82. 2002. [PubMed]

- Arabatzi, F, Kellis, E, and Saez-Saez de Villarreal, E. Vertical jump biomechanics after plyometric, weight lifting, and combined (weight lifting + plyometric) training. J Strength Cond Res 24(9): 2440–2448, 2010 [PubMed]

- Chaouachi, A, Hammami, R, Kaabi, S, Chamari, K, Drinkwater, EJ, and Behm, DG. Olympic weightlifting and plyometric training with children provides similar or greater performance improvements than traditional resistance training. J Strength Cond Res 28(6): 1483–1496, 2014. [PubMed]

- Hori, N., Newton, R.U., Andrews, W.A., Kawamori, N., McGuigan, M.R., and Nosaka, K. (2008). Does performance of hang power clean differentiate performance of jumping, sprinting, and changing of direction? Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 22(2), pp.412–418. [PubMed]

- Carlock, J.M., S.L. Smith, M.J. Hartman, R.T. Morris, D.A. Ciroslan, K.C. Pierce, R.U. Newton, E.A. Harman, W.A. Sands, and M.H. Stone. The relationship between vertical jump power estimates and weightlifting ability: A field-test approach. J. Strength Cond. Res. 18(3):534–539. 2004. [PubMed]

- Laffaye, G., & Wagner, P. (2013). Eccentric rate of force development determines jumping performance. Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering, 16(1), pp.82–83. [Link]

- Laffaye, G, Wagner, PP, and Tombleson, TIL. Countermovement jump height: Gender and sport-specific differences in the forcetime variables. J Strength Cond Res 28(4): 1096–1105, 2014 [PubMed]

- McLellan, CP, Lovell, DI, and Gass, GC. The role of rate of force development on vertical jump performance. J Strength Cond Res 25(2): 379–385, 2011 [PubMed]

- Slawinski, J, Bonnefoy, A, Leveˆque, JM, Ontanon, G, Riquet, A, Dumas, R, and Che` ze, L. Kinematic and kinetic comparisons of elite and well-trained sprinters during sprint start. J Strength Cond Res 24(4): 896–905, 2010

- Stone, MH, Sands, WA, Carlock, J, Callan, S, Dickie, D, Daigle, K, Cotton, J, Smith, SL, and Hartman, M. The importance of isometric maximum strength and peak rate-of-force development in sprint cycling. J Strength Cond Res 18(4): 878–884, 2004. [PubMed]

- Leary, BK, Statler, J, Hopkins, B, Fitzwater, R, Kesling, T, Lyon, J, Phillips, B, Bryner, RW, Cormie, P, and Haff, GG. The relationship between isometric force-time curve characteristics and club head speed in recreational golfers. J Strength Cond Res 26: 2685–2697, 2012. [PubMed]

- Haff, GG, Stone, MH, O’Bryant, HS, Harman, E, Dinan, CN, Johnson, R, and Han, KH. Force-time dependent characteristics of dynamic and isometric muscle actions. J Strength Cond Res 11: 269– 272, 1997. [Link]

- Canavan, P.K., G.E. Garrett, and L.E. Armstrong. Kinematic and kinetic relationships between an Olympic-style lift and the vertical jump. J. Strength Cond. Res. 10(2):127–130. 1996. [Link]

- Gourgoulis, V, Aggeloussis, N, Garas, A, and Mavromatis, G. Unsuccessful vs. successful performance in snatch lifts: a kinematic approach. J Strength Cond Res 23(2): 486–494, 2009 [PubMed]

- Campos J, Poletaev P, Cuesta A, Pablos C, and Carratala V. Kinematical analysis of the snatch in elite male junior weightlifters of different weight categories. J Strength Cond Res 20: 843–850, 2006. [PubMed]

- Garhammer J. Biomechanical profiles of Olympic weightlifters. Int J Sport Biomech 1: 122–130, 1985. [Link]